-

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Days Won

184

Everything posted by Roy B

-

Pics in the gallery. Many thanks to Nic for taking them 👍

-

Many thanks to you both 👍

-

Results - Northampton Shaleway - Saturday 23rd March 2024

Roy B replied to nic's topic in Essential Information

Thank you Nic 👍 -

Many thanks Nic 👍

-

Pics now in the gallery - Many thanks to Nic for taking them 👍

-

GN Notes: 295 leads away. 580 gets spun by the pack coming to the green. This causes chaos on the home straight involving many cars ending up scattering in all directions. Caution Seven cars do not make the restart. 352 leads off. 548, 120 and 73 tangle in turn 1. 446 hits the fence in turn 1 and ends up stopping on the exit of turn 2 which brings out another caution. 352 leads away once again with 345 behind. 55, 16 and 515 engage in a great bumper fest battle. Caution for debris. 352 has 515, 16, 5 and 55 behind him for this restart. 515 soon takes the lead. 5 and 166 have the sparks flying as they trade blows. 63 stops in turn 1 which causes 16, 55 and 166 to tangle momentarily. Caution. 55 retires before the green. 515 leads away and moves ahead of the chasing pack to the win. 16 retires in a cloud of steam. At race end 5, 166 and 463 are nearly 1/2 a lap behind the Silsden Sizzler 👍 That's it folks. I'll be back from Buxton on 13th April 👍

-

Final Focus: 295 leads away but spins it coming to the green. 345, 545, 453 and 554 pile up in a heap at the end of the home straight. 55 and 120 tangle on the home straight slowing both. 268 stops on the exit of turn 2. 446 retires with a flat front right. 5 tangles with the stationary 295 car on the exit of turn 4. Caution to move stranded cars. 82 heads the restart. As the reds charge into turn 1 16 fires a big hit in at the back of the train. 55 follows suit but bounces off. 166 and 216 tangle in turn 3 with Bobby remaining there for the remainder. 124 leads. 55 and 175 tangle on the exit of turn 4. 326 goes wide in turn 1 which allows 16 and 515 through. 63 spins in turn 1 under pressure from 55. In the closing stages 515 suffers another flat right rear. 124 takes the win 👍

-

Consolation Catch Up: 404 leads away. 443 spins in turn 1 on lap 1. 82 into the lead. 404 ricochets off 73's nerf rail in turn 3 and hits the fence. 453 goes around on the home straight. Caution to move 404 to safety. 82 heads the restart. 5 drifts wide through the turns losing time. 515 elbows 166 aside through turn 1. 446 is giving chase to the rapid 82 car. 443 has stopped on the outside of turn 2 with the nose pointing towards the infield. This narrows the racing line which catches out 350, 469 and 375. 515 takes advantage and nips up the inside of 446 in the melee. Next time around Frankie takes the lead. At 5 to go 580 gets a tankslapper on the home straight in front of the leader. Frankie has a split second to choose the right side to get through. 446 and 166 engage in battle near race end. As 515 takes the win 5 and 82 dice for position as they come to the line. Charlie on the outside eases Karl towards the infield as they cross the line.

-

Heat Two Happenings: 295 leads away. 73 spins on the home straight on lap 1. H337 clouts the turn 1 fence and retires with a flat front right. 216 bounces off a marker tyre on the back straight. 191 and 5 clash in turn 3. 381 and 166 both come to a stop on the outside of turn 1. 404 retires to the back straight infield. 346 slows and stops on the exit of turn 4. 95 leads. 191 retires with smoke billowing out of the left side exhausts. 580 spins in turn 1 nearly taking 95 with him. 515 retires with a flat right rear. At two to go 124 and 55 have edged closer to the flying Mitchell machine. 1 to go sees 55 take 2nd from 124. 95 takes the win. Post race Rob thanks everyone who has helped over the past 18 months to get the car finished. A great debut for the car 👍

-

Welcome to the 2024 season folks. We kick it off with the W & Y Eric Graveling Race Recap: 548 leads away. 548 half spins in turn 3 with 163 sending him fully round. 469 leads. 163 leads lap 2. 545 spins onto the home straight infield. 82 takes over up front. 163 makes a challenge in turn 2 drifting up the track. 82 spins the lead away in turn 4. 163 leads once more. 268 takes the spot as they come through turn 3 for the last time and gets the win.

-

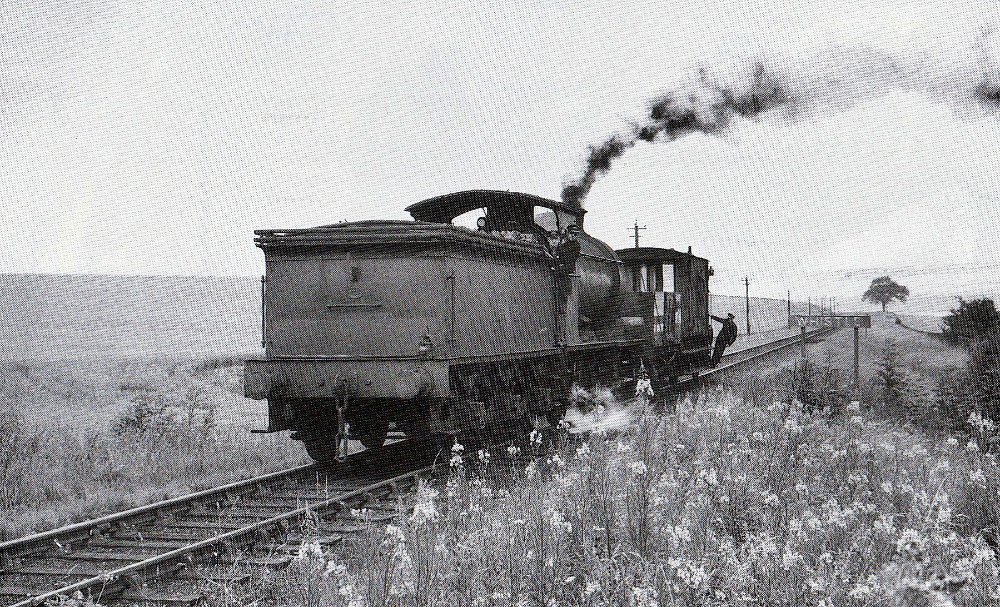

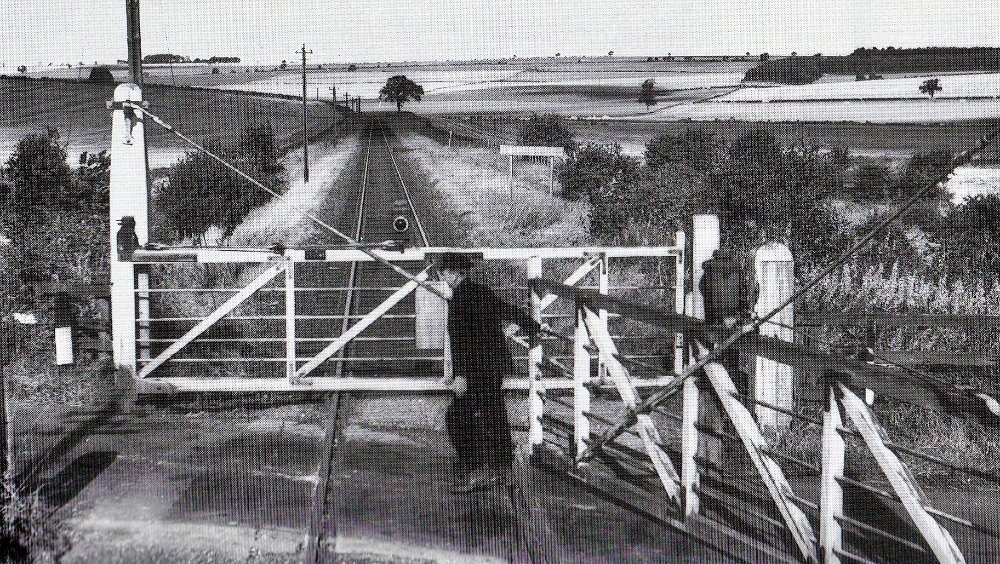

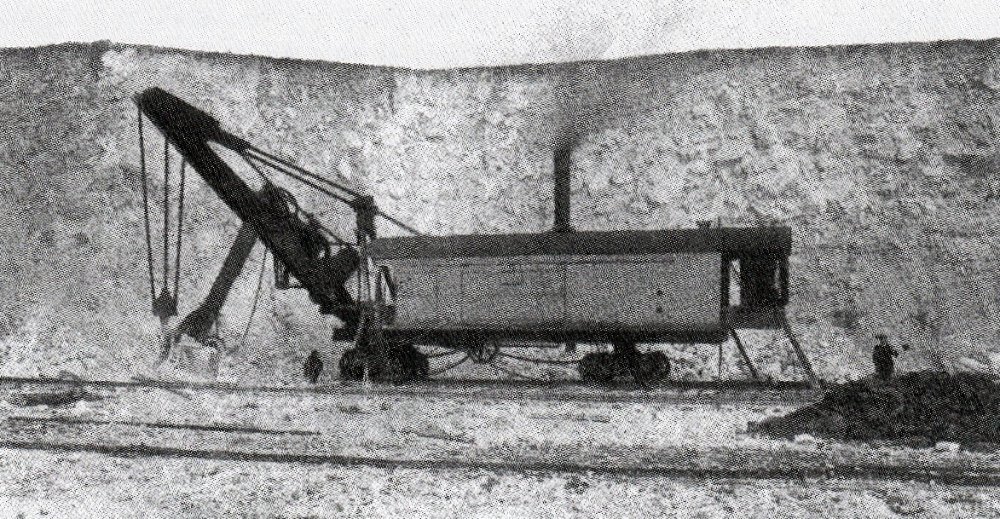

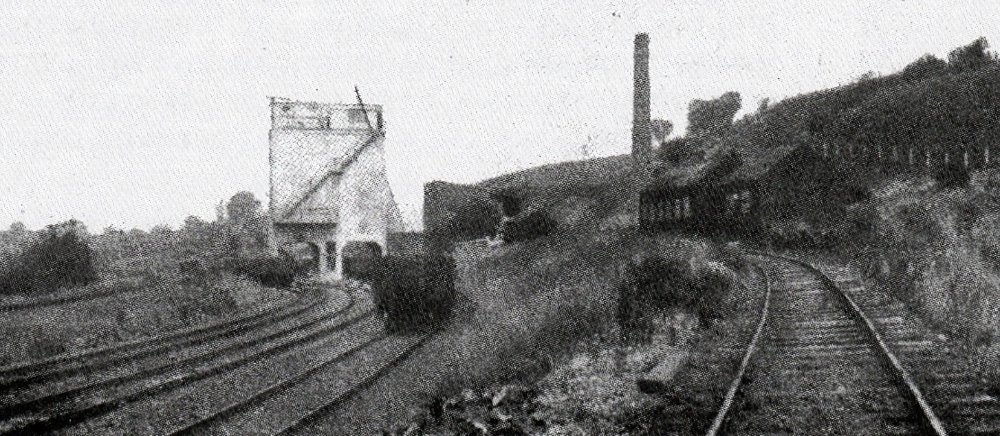

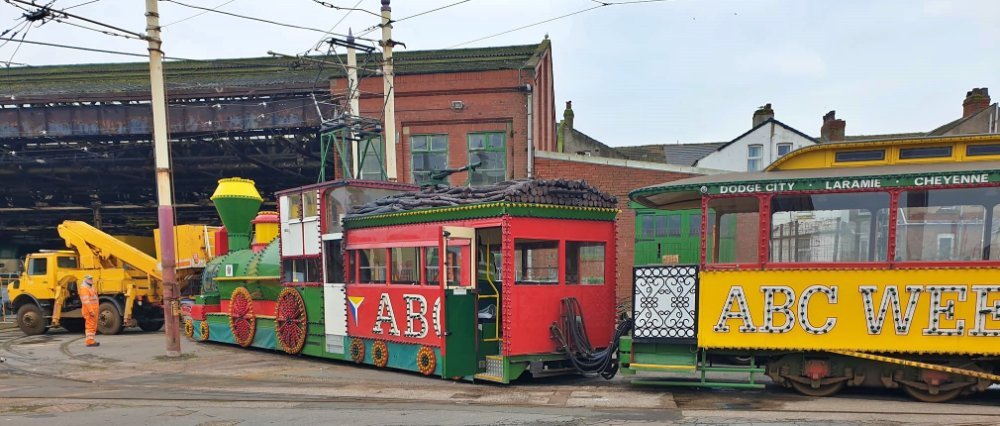

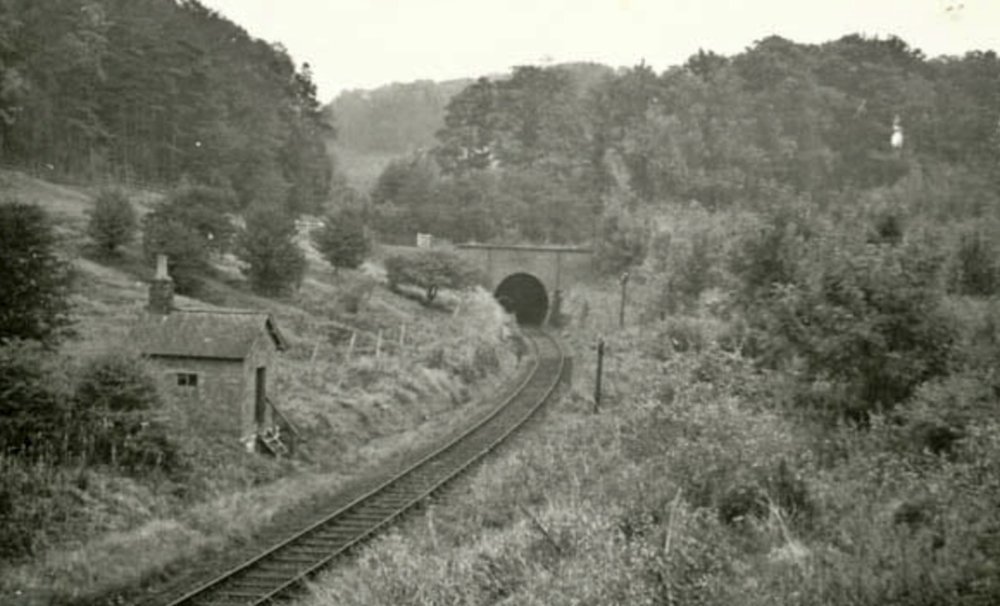

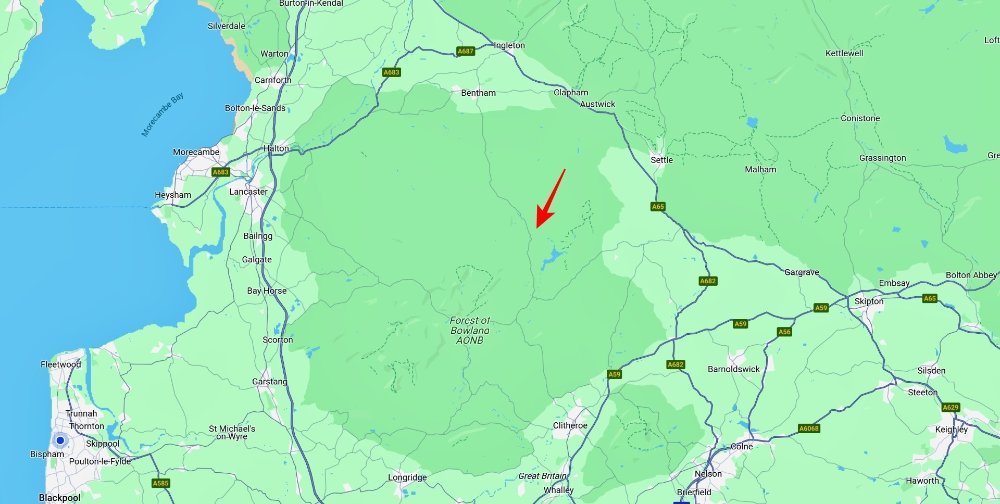

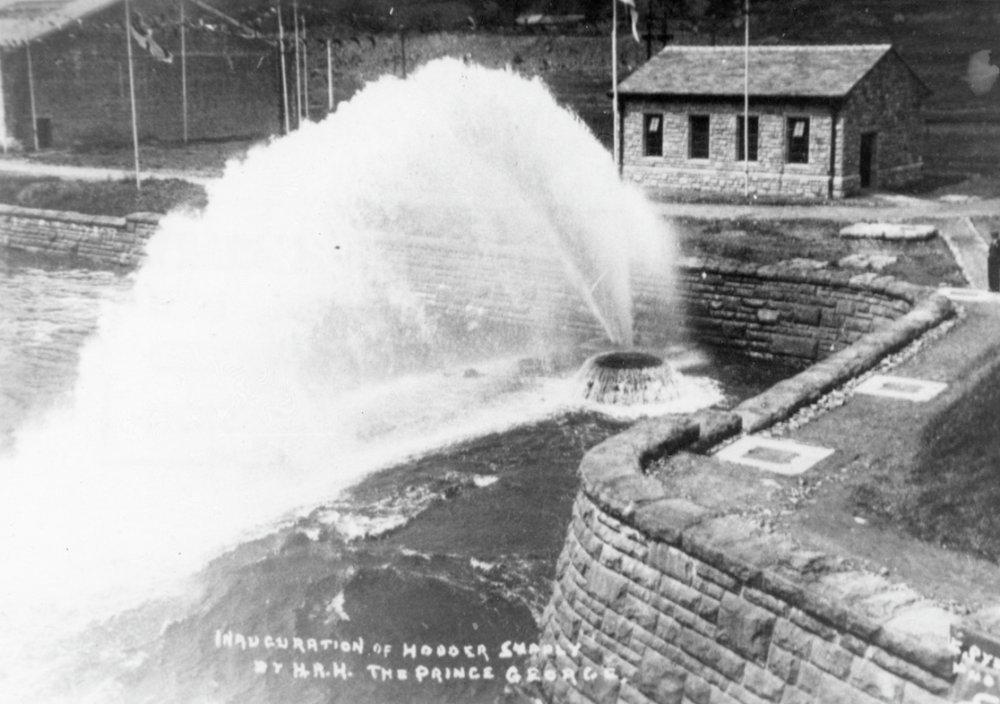

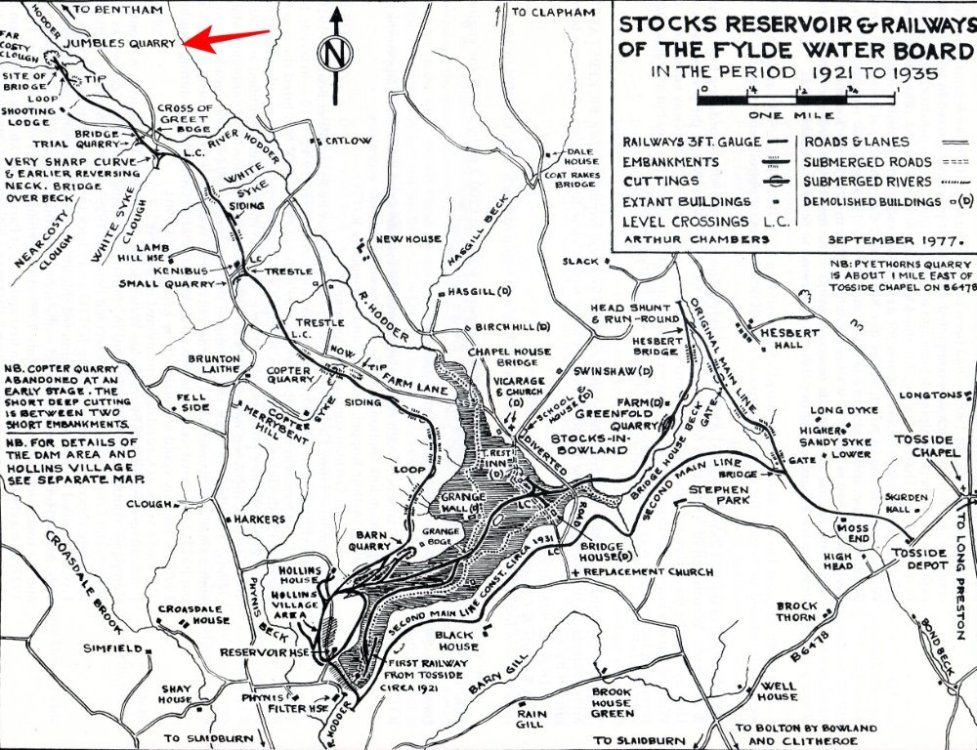

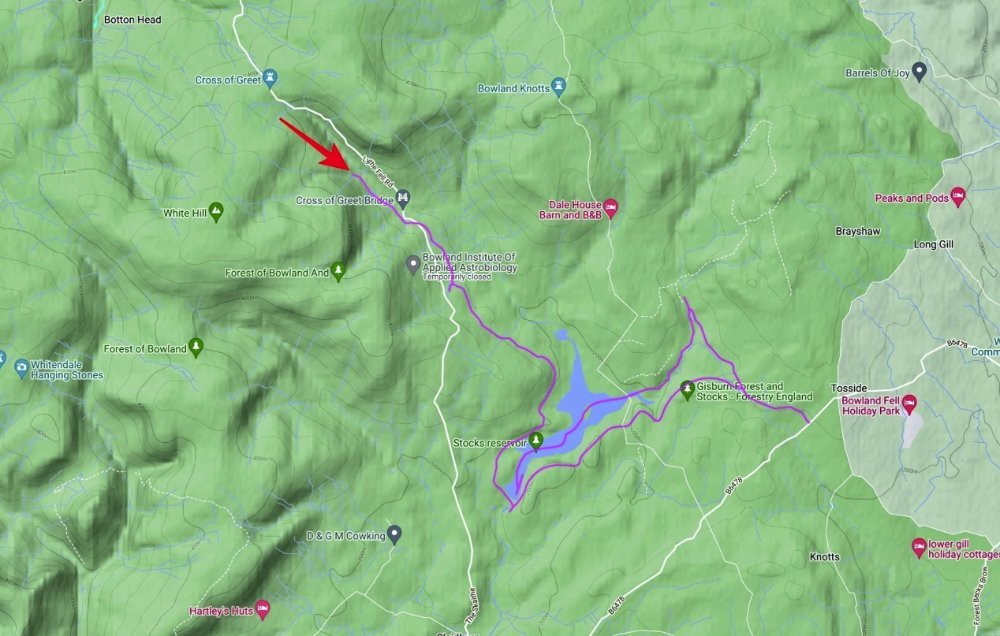

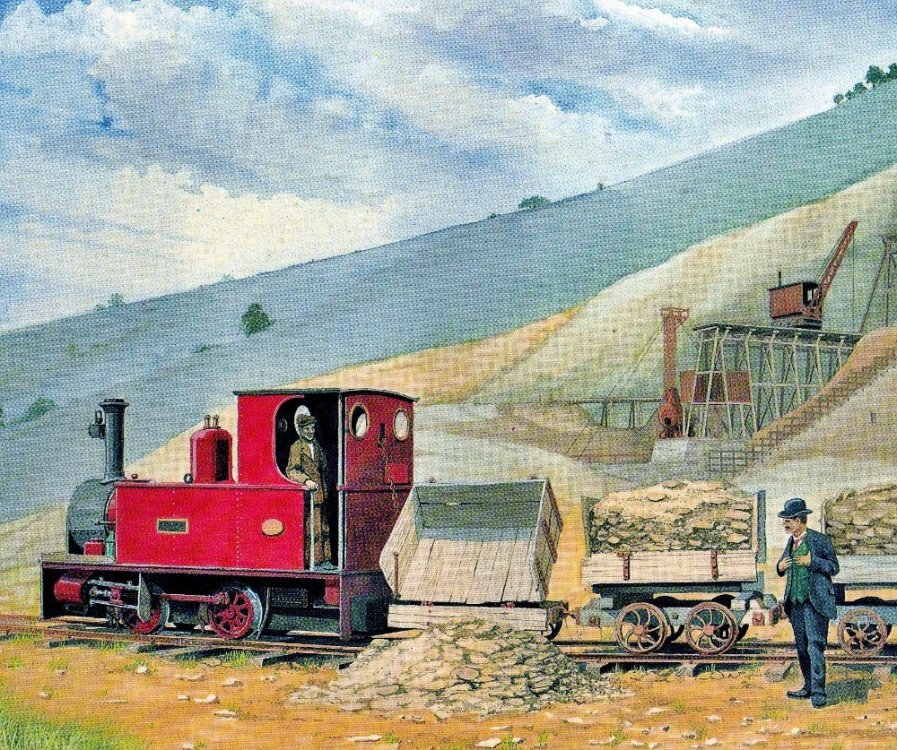

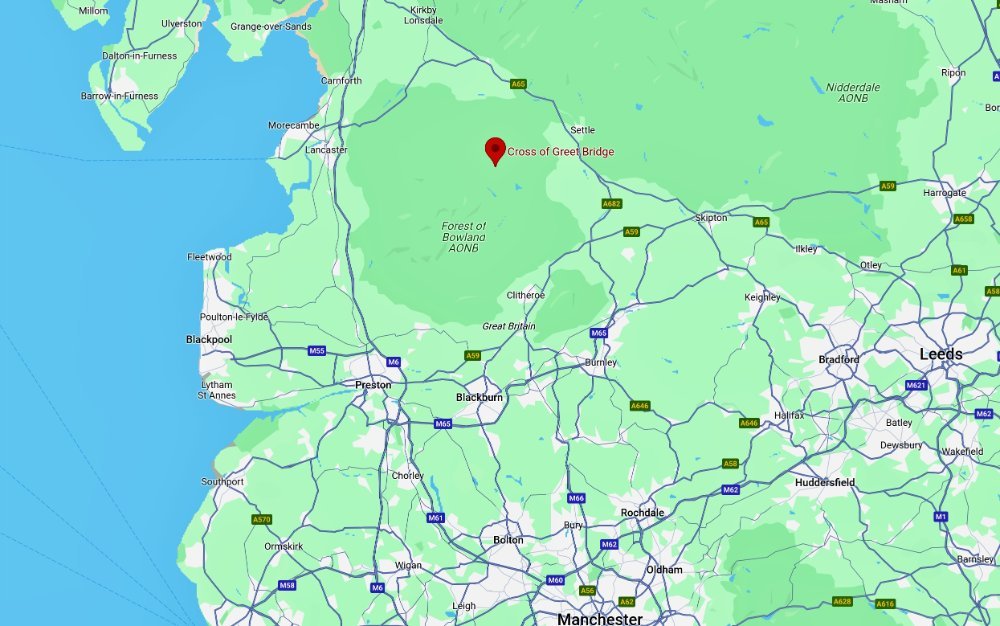

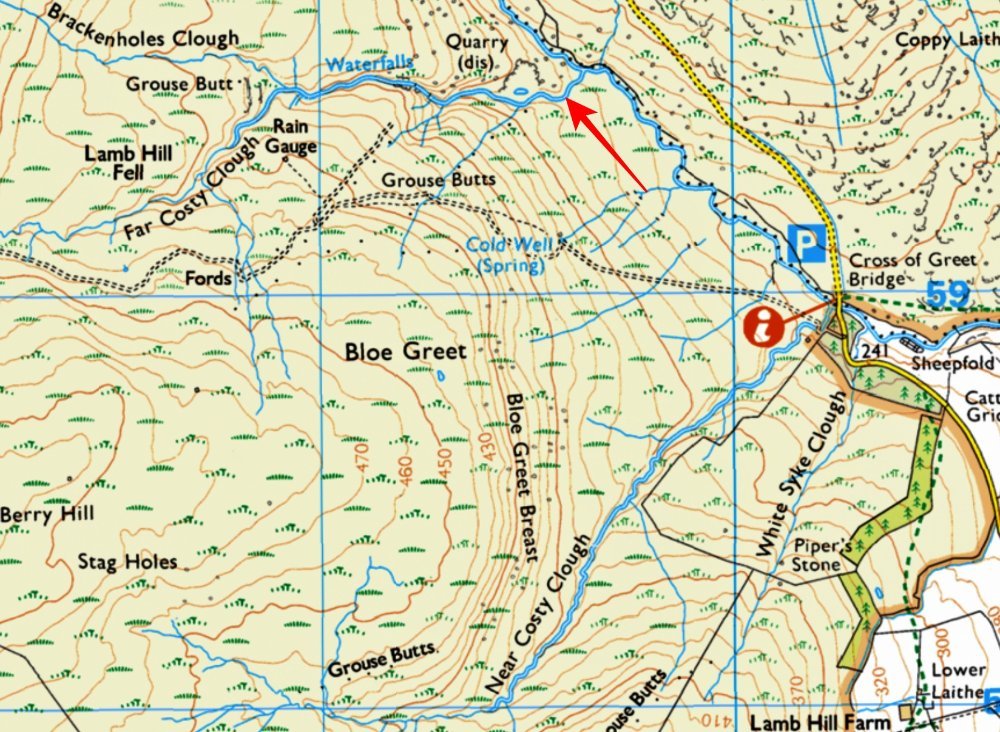

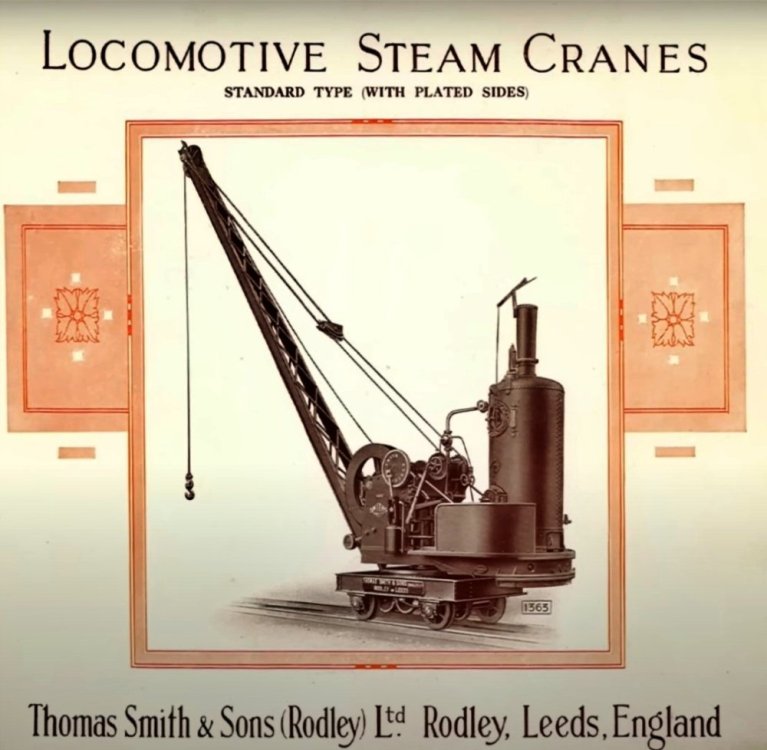

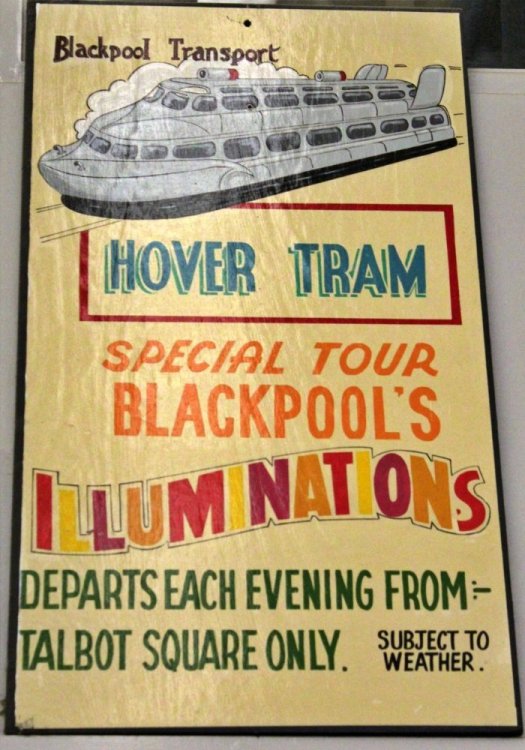

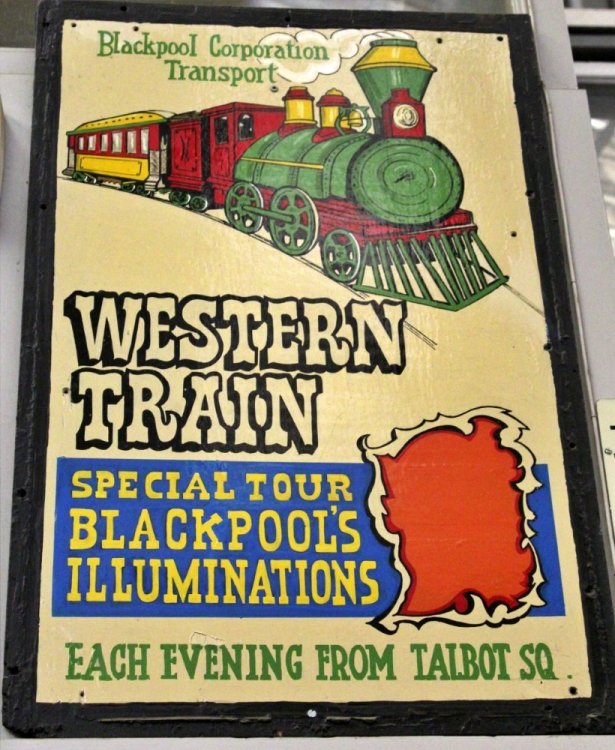

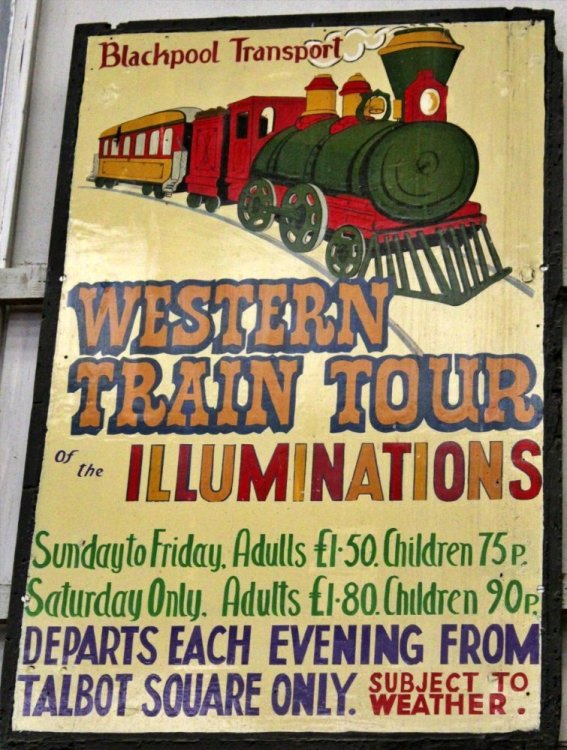

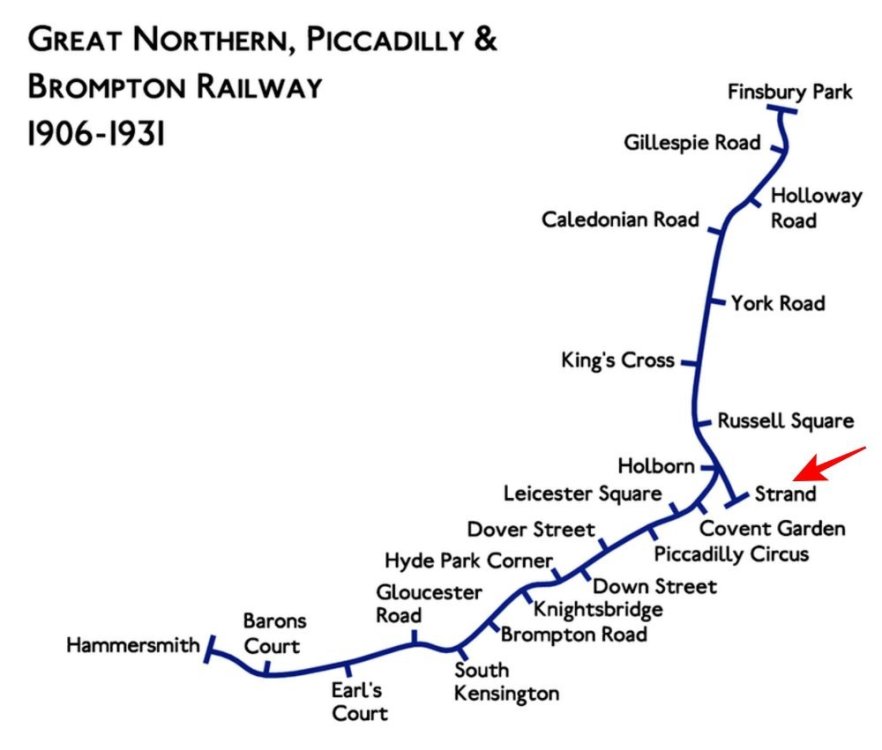

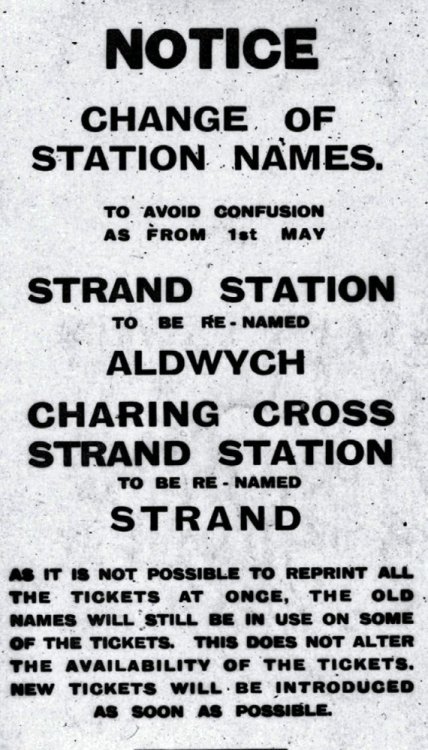

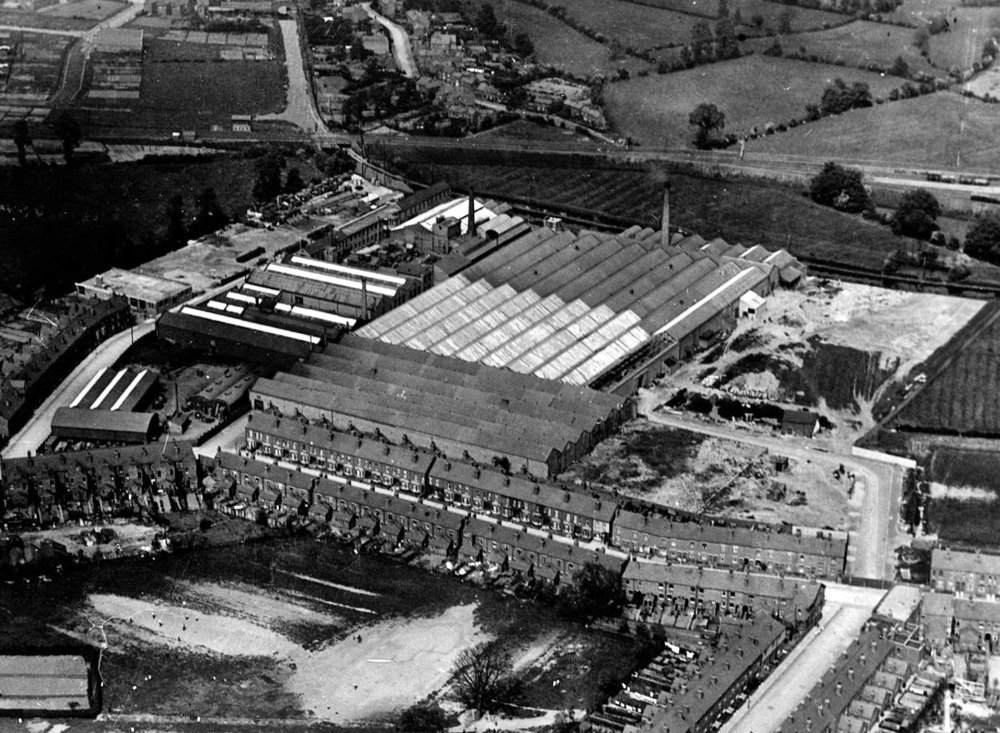

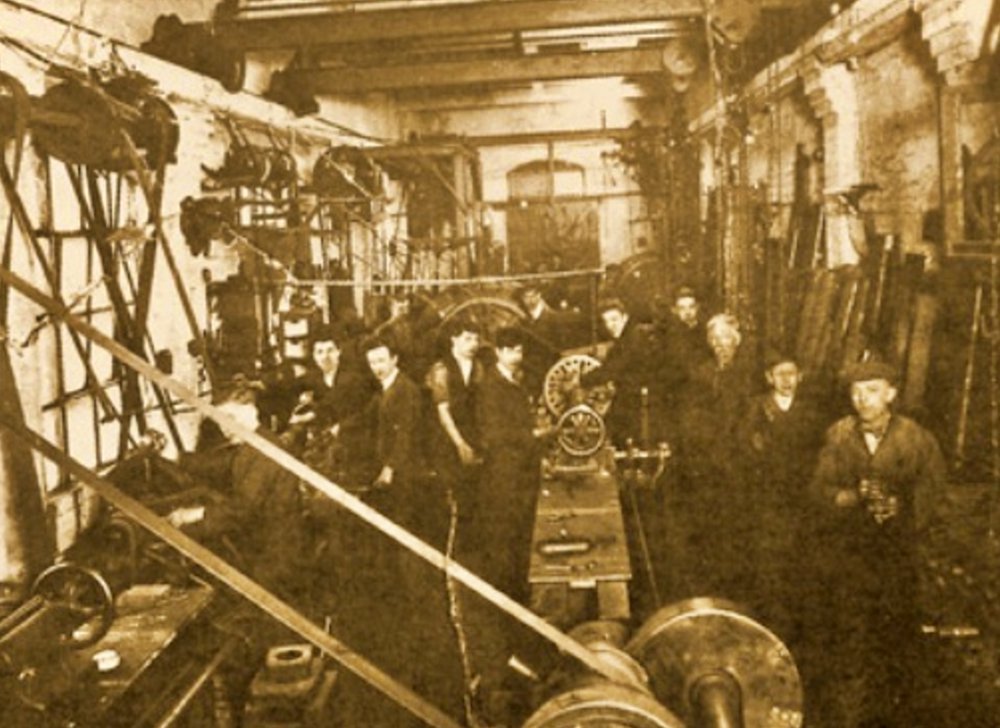

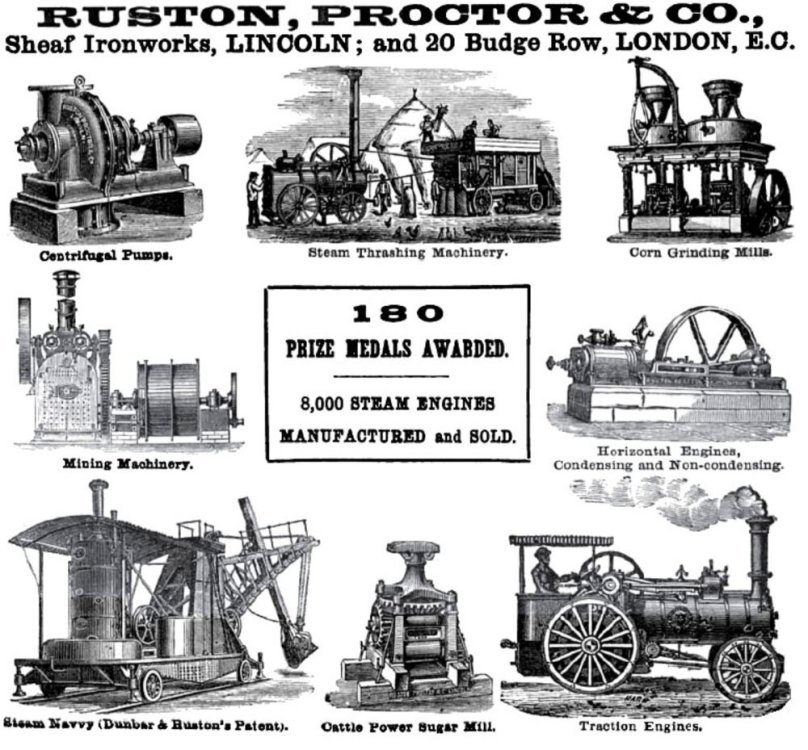

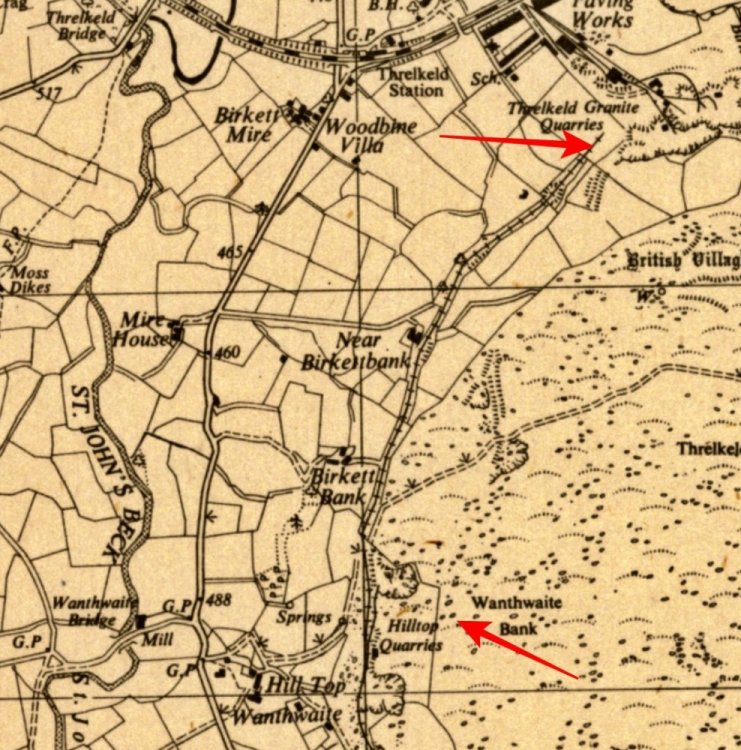

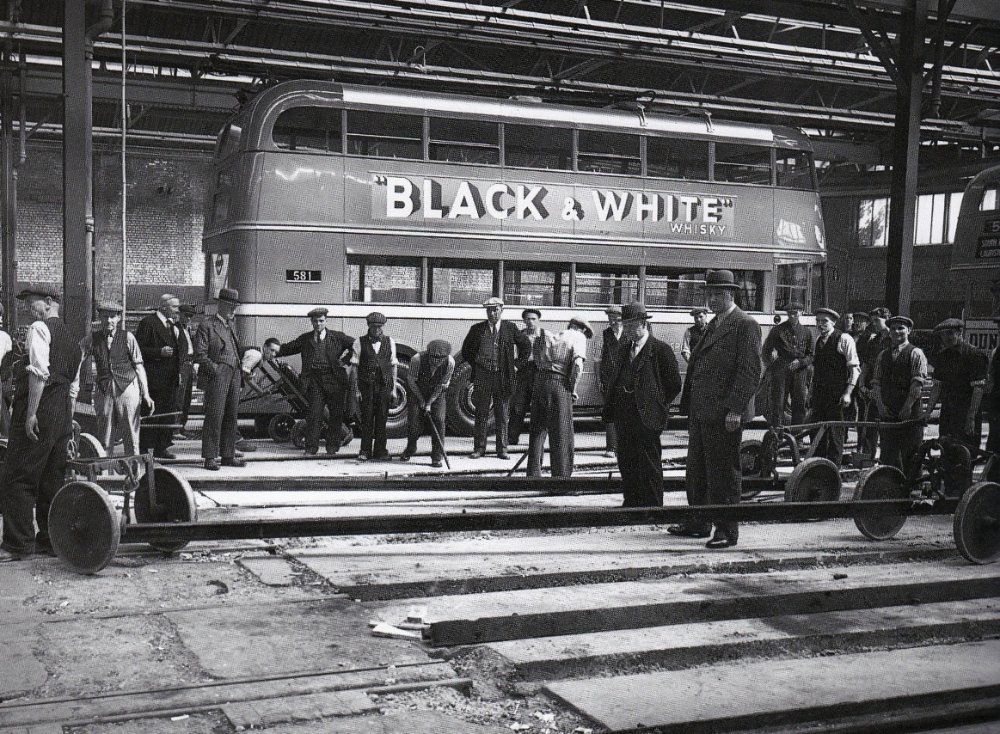

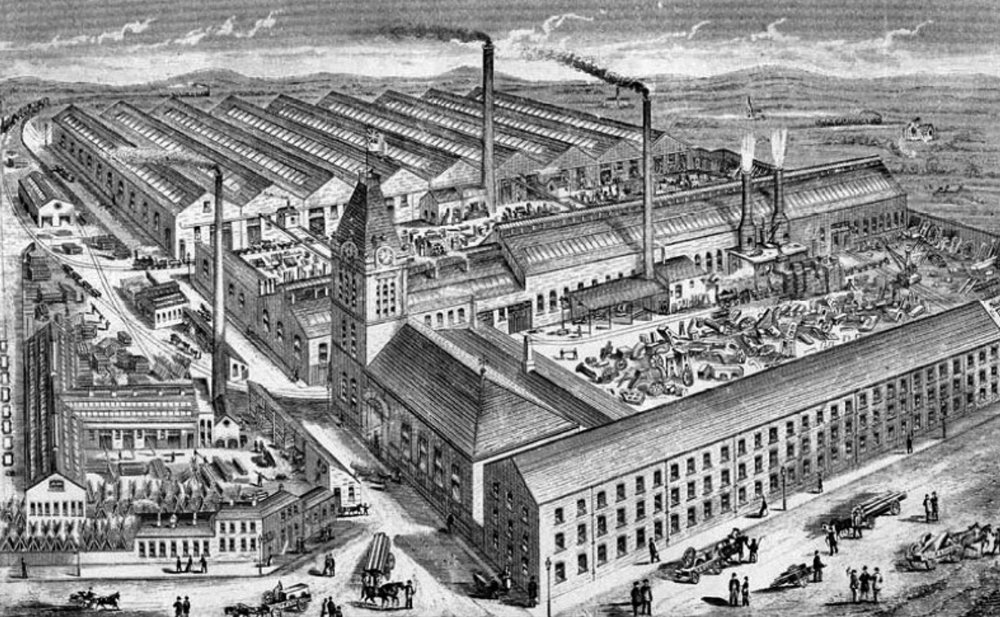

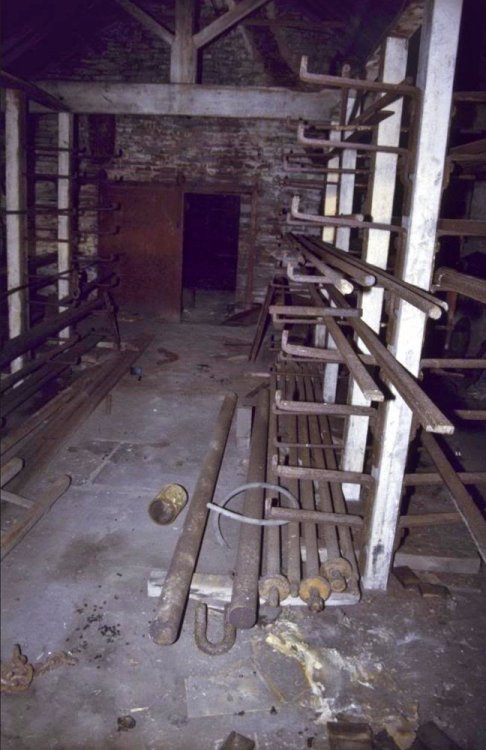

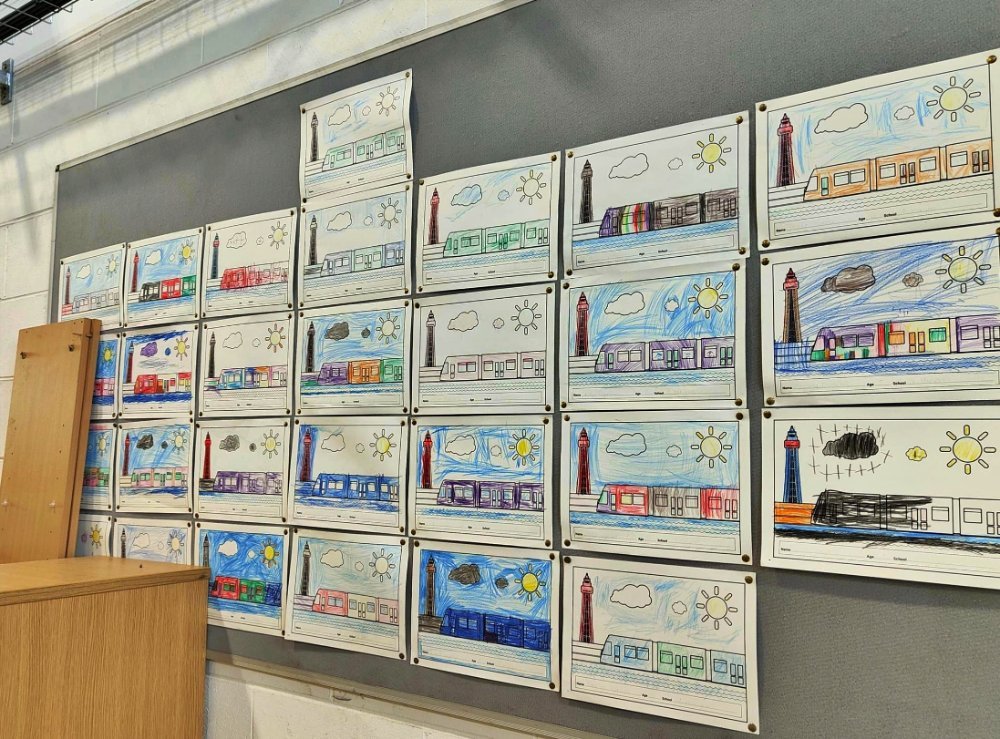

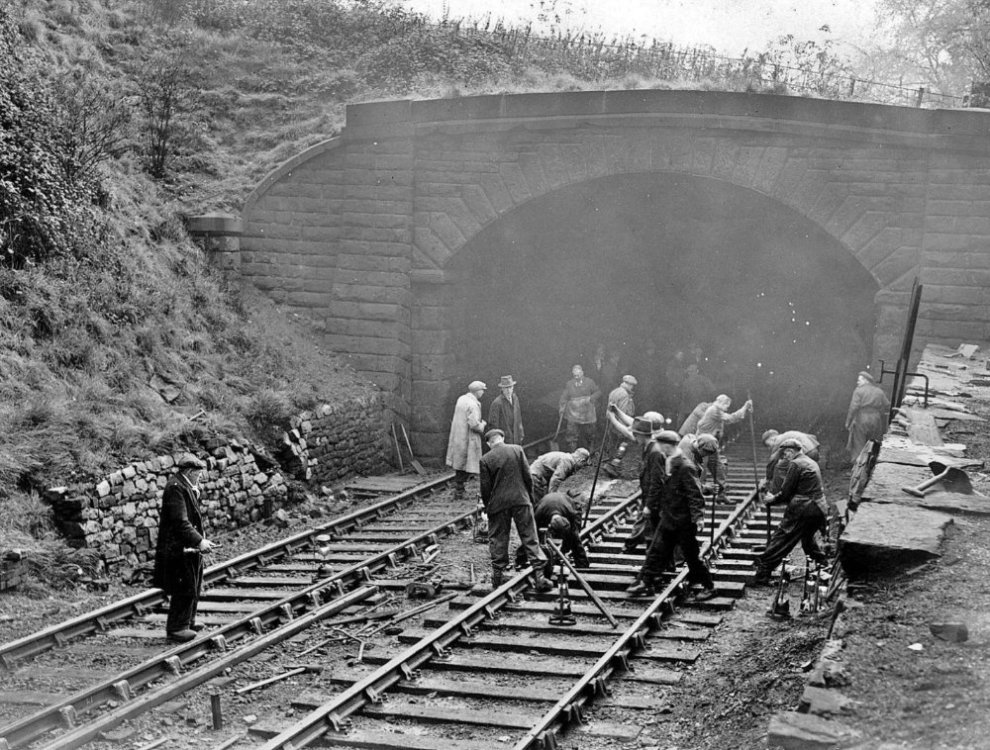

Hi there folks. Welcome to episode 9. In this last one of this off season: Section 1: Pics from the Saloon WF weekend at Taunton and the end of season bash at the same circuit + a few pics from last weekend’s Cowdie. Section 2: In Out and About we’ll have a look at the abandoned Wharram Chalk Works Section 3: Odds and Ends: Pics of London’s trolleybuses in wartime, a Leyland Leopard for Abbotts Coaches, Blackpool Transport archives, this week at Rigby Road depot plus East Lancs pics from today (Fri 15th). Section 1: Taunton – Saturday September 30th – 61 Saloons & 55 F2s / Sunday October 1st 2023 In the weeks preceding this meeting there had been a degree of controversy following Nick Antwerpen’s (H153) exclusion from the Saloon Stock Car World Final by the promotion. This followed Antwerpen’s extensive criticism of the Saloon Stock Car Association and the Autospeed promotion. After a review of the matter, an apology from Antwerpen, and some constructive dialogue with driver representatives H153 was reinstated. However, there were still some ill-informed outbursts on social media about the situation from other people. The note on the left-hand side relates to this. The F2 GN Championship was raced for on Saturday. Memories re-lived The Saloon WF trophies Graeme Shevill 661 - There’s no danger of this coming loose Ministox graduate Harley Soper Harley was in the ex-Brad McKinstry car An engine change for the Farrell team Craig Driscoll was in the Courtney Witts car The Taunton track is on the wartime Upottery Airfield, hence the concrete surface which used to be a runway The back of the grid and the front A good crowd Joe Powell beached An early finish for these two in the GN Championship race Saloon WF result: 730 720 600 561 120 349 153 618 131 122 F2 GNC result: 783 24 92 127 890 184 390 475 736 895 Sunday pics: Deane Mayes – The 2023 Saloons World Champ Ballast arrowed on 560 A front end repair for Joe Grandon A picture on the notice board on Sunday featuring Billy Smith (161) Not a good day for the 475 car Leah and Sam Weston discuss their race retirements Another trip to the wall for Steven Gilbert Sam and Leah are joined by Steven and Ben Goddard 475 – New front bumper required Major damage for Jessica Smith towards the latter part of the meeting after a big fencing from Jon Palmer Andy and Jess walk the car back to their pit Plenty of folks willing to lend a hand Taunton – Sunday October 22nd 2023 – 35 cars Behind the Paul Moss car is a regular visitor (arrowed) to the Autospeed circuits Travelling from the north east has obviously taken its toll! Harley Soper up to yellow Rear end work on 647 Likewise for Dan Roots Ben Spence was in the Liam Rennie car It was a National Points Series round which Guinchy was hoping to score well in James Matthews was in the Rygor car Whilst Craig Driscoll was in JP’s Jon was on tyre delivery duty to the geographical agents A big stack for Luke Wrench and for Chris Burgoyne Timmy Farrell – the car looking great with this paint job This meeting was for the Ladies Trophy. It serves as a long-standing memory to Marylin Farrell mother of Timmy and former F2 driver Rob Momentoes were given out to the participants Two members of the Farrell family parade the trophy through the grid Adam Pearce uses the 654 car as a launch pad Rob Farrell (ex-770/870) looks on as Aaron Vaight receives his 2nd place trophy Gordon with the spoils of victory alongside the Farrell family Alan McLachlan (Cowdie and Autospeed) commentator interviews Gordon Guinchy, Julian Coombes and Rob give the Flying Fifer the traditional champagne overcoat Martin and Stella Farrell join Gordon on his victory lap A dominant performance Gordon flanked by Martin Farrell (ex-770) & Rob A few pics of new/refurbs from Cowdie last Sat (9th): Reece McIntosh Ryan McGill John Hogg Paul Reid Jordan Cassie Nicole Russell Declan Honeyman Robbie Bruce Dale Robertson Harry Bruce An 11yr old Merc Section 2: Out and About – Wharram Chalk Works We’ve not far to go from last time’s Burdale Tunnel visit as the chalk works were just to the north. Before we head there here is a wonderful painting depicting the line into Burdale Tunnel with Tunnel Cottage and the hut on the approach to the tunnel entrance: It was a very rural area indeed. 65849 comes to a stand at Garton Slack so that the guard may climb down to open the level crossing gates on August 7th 1958 He shuts them again after the train has gone across Settrington Station looking towards Malton in 1926 Station Master Thomas Sleightholme (1883-1983) with porter-signalmen Burton and Webster at Wharram circa 1935 We’ll make our way to the site of the quarry now: The track bed of the railway is our guide. Notice the old lane crossing over above. On the lane Water from the surrounding land was channelled under the bridge This channel leads to a flight of steps However, the water has chosen a different route over the years It enters a covered section It then makes its way along an open brick-lined channel which is of great length A tree has grown up against the bridge with the roots causing some major cracks to appear Quarrying began here in 1919 but it is now a nature reserve, a peaceful place Decades back it was noisy and dusty. A Ruston & Hornsby steam digger at work in April 1926. A close up of the digger The spoil heaps are slowly being reclaimed by nature The quarry had its own Andrew Barclay 0-4-0 shunting engine The quarry was operated by a company called Casebourne & Co, who also made concrete, the available chalk nearby being ideal for this purpose. The quarry itself dates from 1916 and closed for a period in the 1930's but production did start again a few years later. At its peak in the 1920's the quarry produced over 100,000 tons a year. The chalk was also used in making lime (with the lime kilns on site), and as a flux in the iron and steel works in Teeside. The kilns just about survive. Looking into the kiln from above Chalk was extracted here and transported via the sidings and railway line close by. A cabin still remains in pretty good condition. The high-quality chalk extracted was used for agricultural purposes and in cement-making – the railway line took it to the cement works of Casebourne & Co, at Billingham, Leeds and Durham. The railway line closed on the 20th October 1958. # Before going on its way it was crushed in the buildings alongside. The iron window frames have seen better days The silo comes into view The 'Stein' brand is believed to have been manufactured in Scotland by J G Stein who had works in the Castlecary / Bonnybridge area, and at Manuel near Linlithgow. In 1967 J G Stein amalgamated with General Refractories of Sheffield and became GR Stein Refractories. This company was then taken over by Hepworth Ceramic Holdings and eventually became known as Hepworth Refractories. Another takeover took place when it became Premier Refractories but this did not last very long because it was bought by Vesuvius and is now part of the Cookson Group. The engine house Trucks were moved along the concrete gantry The large concrete silo. These buildings are perhaps a little easier to see in the winter when the vegetation has died back. There were many interesting features to be seen inside, however there was no way to the upper levels of the silo as the iron staircase had given up the ghost long ago. This is where the bulk chalk was unloaded Crushed chalk was dropped down the chutes into the waiting trucks three tons at a time The hopper mechanism still worked The remains of a pulley wheel. The wire would have been connected to the chute for open and closing. The control room for the hoppers The base for a generator Inside the tower Looking down into the chalk crushing house The trucks were lined up in here and the chalk tipped into the crusher alongside This grainy photo shows the scene when active The view today The operation of the quarry can be seen in this short film: Section 3: Odds and Ends The London trolleybuses in wartime: K1 1128 was left in this state after major blast damage in Stoke Newington on 18th September 1940. The vehicle was rebodied in 1942. Most damage to vehicles was inflicted by blast, and in one such incident, L3 N0.1439 has had all of its windows blown in or broken. It is the subject of much scrutiny as it stands outside the Methodist Chapel in Benledi Street, Poplar on 10th December 1940. D3 class trolleybus 530 is being used here to demonstrate the virtues of the protective wire netting which was glued to the window glass. The bodywork has not suffered much damage beyond having a number of windows blown in, but there is a dent visible in the rear lower panel. Bow depot on 26th September 1940. Structural damage has been suffered and N1 1622 has been affected along with a few others. New panels and glass would soon be fitted, and the travelling public would probably not even be aware of the work needed to keep the service running. K1 class No. 1123 had its body written off after an incident at Dalston on 8th November 1940, the day after Bexleyheath depot was hit. The severity of the blast can be clearly seen here as it stands in Stamford Hill depot awaiting assessment. Its new body was supplied in December 1941. Abbott's Coaches Duple Dominant/Leyland Leopard EFR 97W They were delivered to Cleveleys garage from Duple and had to have the chrome trim covered in Vaseline, for protection, before being driven to the booking office in Albert Road, Blackpool to be parked up for the winter. From the Blackpool Transport archives: Brush car 636 at the top of the depot during winter 2003/4. The tram had been repainted into Metro Coastlines line 14 colours but had yet to receive the livery vinyls. Unfortunately, this repaint which involved the panelling over of the curved roof windows (636 being the last of its type to retain these) cost the tram it's "celebrity status", and possibly a place in the retained heritage fleet. It was withdrawn from passenger service less than a year later. Its final resting place left abandoned in a field 634 being moved around the depot on 22 September 2018 The next five pics are from the 1960s: Standard 160 on the traverser at Rigby Road depot. The long gone gasometer dominates the background. The Western Train at Talbot Square Inside Rigby Road depot Rigby Road depot this week: Bolton 66 was brought out for some fresh air on the depot fan The Western Train was towed from Starr Gate depot by the Unimog It was heading for the electrical shop with a compressor fault but was able to enter under its own power which it can do using the handbrake. As a requirement of funding its last overhaul ABC Weekend Television had to remain on the trailer East Lancs Legends of Steam Gala – Friday 15th March 2024 All pics apart from the last three were taken at Ramsbottom Sir Nigel Gresley Leander Britannia 51456 LYR renumbered from 732 Over the crossing An awkward reverse for Fagan & Whalley A good spot for trucks – Pawson Transport Armstrongs At Ramsbottom signal box Gresley heads for Rawtenstall Leander runs around at Rawtenstall That’s it for this off season folks. We’ll return in November to face a big challenge in battling through this lot to find a very remote disused station 👍

-

11

-

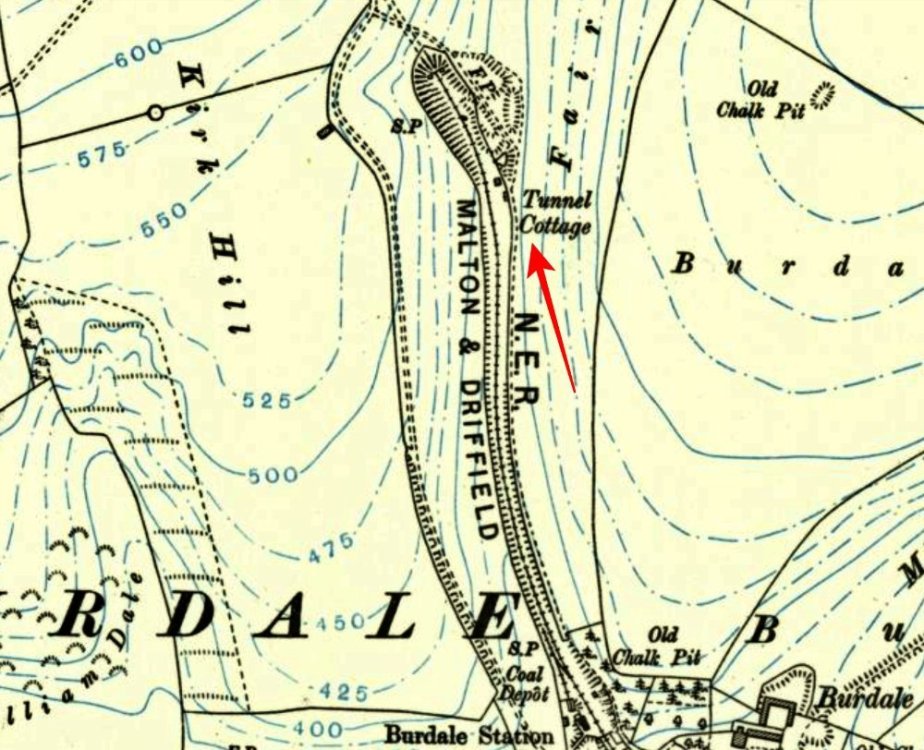

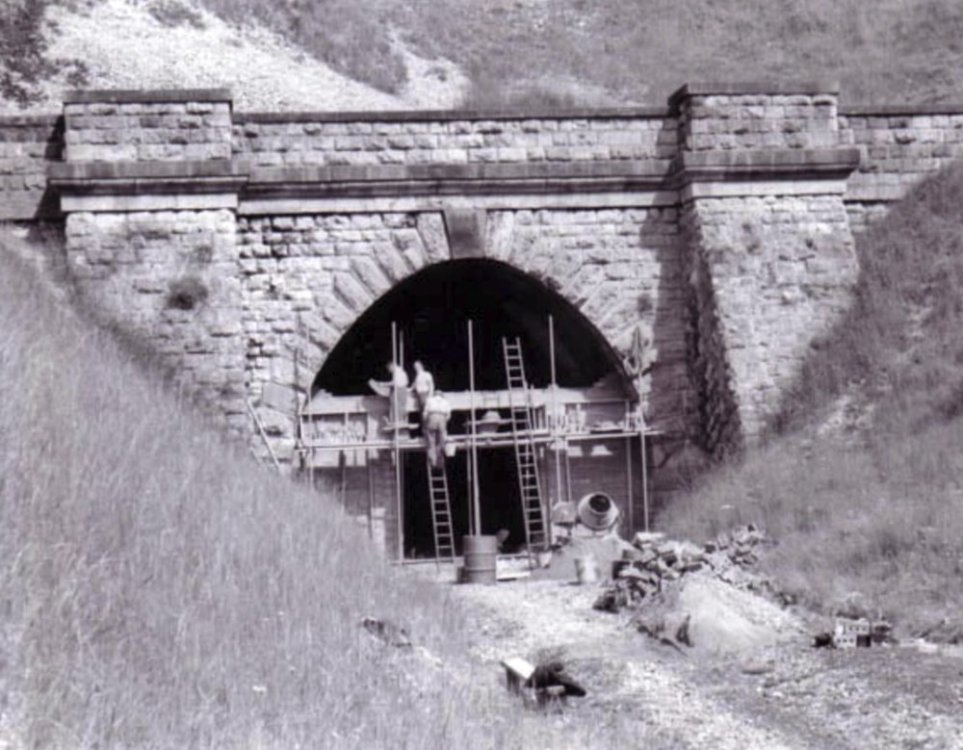

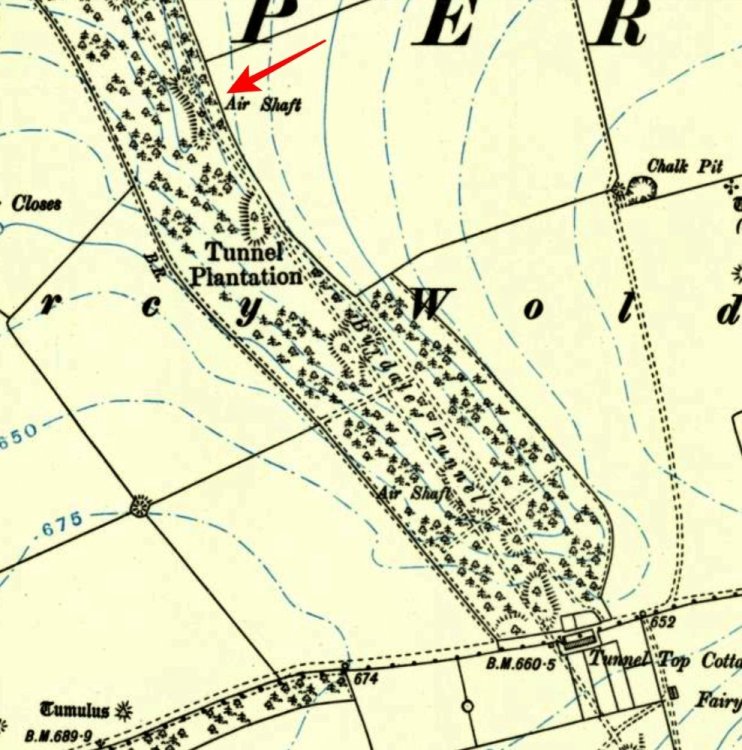

Hi there folks. Welcome to episode 8. Last time I mentioned we would have two main features but I have decided to keep the second one for the last episode in two weeks time as they are both in the same area. In this one: Section 1: F2 World Final meeting at Nutts Corner. Section 2: In Out and About we see how far we can get through the disused Burdale Tunnel. Section 3: Odds and Ends: The 2023 Leyland Gathering at Quainton Section 1: Before we cross the Irish Sea here are a few pics from the F2 meetings over here in the three weeks prior: Taunton – Monday 14th August 2023 Following the damage to his car from the St Day fixture the day before JP raced the Lauren Stack (928) car at this meeting It proved to be a good’un netting Jon the Final victory Some aggro in the ORCi Stock Rods with David Philp Jnr being followed in! Bristol – Sunday 27th August 2023 Spotted in the car park was this 21yr old Vauxhall hearse A good night’s sleep guaranteed! Weston-Super-Mare’s Dave Rudall Winsford’s Mike Kingston Jnr Josh Walton a long way from his north-east base Another different one for Jon Palmer to race this week - Justin Albrecht’s car Paul Moss - The 2023 track champ’s car for sale Taunton – Monday 28th August 2023 Ryan Croucher made his debut Ben Borthwick was not seen a lot in 2023 but he did secure the English Open Championship at sister track St Day two weeks previously A good crowd Not a good meeting for Charlie Fisher Nutts Corner – F2 World Final – Saturday 2nd September 2023 – 70 cars The following words are from the meeting programme: This is an historic event being the first World Final held outside mainland UK. The promoter Ian Thompson had long campaigned to bring the sport’s major event to Northern Ireland. It was a big ask given the distances, the need for boats, planes and automobiles to carry a considerable number of fans and drivers from all parts of the UK and indeed mainland Europe and further. The hosting nation have long brought colour and atmosphere to the mainland so it was rightly deserved that they got their own day on the ‘World’ stage. This part of the UK is ingrained in the DNA fabric of BriSCA F2 for close on 60 years. At one time the list of venues hosting BriSCAF2 stock car racing was impressive. However, it was regrettable a few years ago that Ballymena closed its doors as improvements there for football precluded the continuance of stock car racing. We go back more years to Aghadowey, a venue that still exists, Portadown, Dunmore Park and Bangor to name but some that celebrated the sport at its height and of course Nutts Corner which at one time also experimented with a separate shale track. In recent years Ian Thompson Junior has joined his father in the promoting reins consistently pushing the awareness sometimes against the tide as Nutts Corner sadly remains the last bastion of BriSCA F2 over here and that in itself is a challenge. It is a fast track with wide sweeping bends similar to a slightly bigger Newton Abbot The 1972 World Champ’s car was on display As was Eddie Finnegan’s 1977 Ballymena winner The WF grid lined up after receiving their trophy mementos - Gordon up first. The front row Charlie Guinchard Luke Wrench Liam Rennie Kay Lenssen Gavin Fegan James Rygor The 880 team bring the car to the grid Jack Witts JP comes to the grid Shea Fegan One of the Netherlands’ contingent was Bram Leenhouts The Bekkers’ team had a four-legged tyre warmer present The defending champ enters the arena Dave was in a relaxed mood All was looking good up front The grid comes to the flag After a couple of rolling laps the green flag was waved and Moodie set off at a rapid pace from his pursuers. Luke Wrench blocked Charlie Guinchard to stop him moving across in the first turn. A big pile up involving Craig Wallace, Chris Burgoyne and others followed which brought out the red flags. The restart was a copy of the original start as Gordon shot away. Guinchy was closer this time but could not make contact with the 7’s rear end as they entered turn 1. As the laps went by Moodie eased away a little until a caution closed the pack up. On this restart Guinchard was quicker away and made contact with the 7 car. Moodie rode out the hit though and pulled clear. This was the tone for the race with the only real change being Matt Stoneman moving through the field into 3rd. He now had Guinchy in his sights At the halfway stage Gordon was well clear and increasing his lead. However, it was not his just yet. Nearing race end Stoneman fired the 183 car hard into turn 1 with both hitting the fence. Although this was a challenge for position it was also a payback hit from the Taunton Ben Fund race earlier in the year. The 183 car continued along the back straight losing a wheel in turn 3 just as Moodie took the one to go board. With Gordon entering turn 3 for the last time a yellow flag was called which set up a one lap dash for the 2023 World Final! The line up was 7 from 3, then NI918, 560 and 24. Gordon made another blinder of a start and he was clear around turns 1 & 2. Into turn 3 Rennie tried for a last bender but was too far back. He had suffered a gear selector problem at the restart so may have made contact without this. He didn’t miss by much though bouncing off the wall in the process. The Flying Fifer took the flag and a well deserved victory. 3 & NI918 followed him over the line with 24 having a great drive to take 4th from the back of the grid. Congratulations to Gordon on his fourth world crown. He was by the far the fastest man on the day. Result: 7 3 NI918 24 560 B96 968 992 801 578 213 100 Sunday pit scene: Did you know that Micky was also a master baker? Mick Whittle came over the water with his stunner Gordon wasted no time in fitting the gold wing The 2023 World Champ on parade Saturday’s Final was run on Sunday following a serious road accident outside the stadium the night before which required the track medics and led to the abandonment of the meeting. Jessica Smith was left stranded mid-turn after a big hit from Shea Fegan The Irish Championship race saw Craig Wallace have this spectacular crash with Jack Morrow (Pic by Anthony Jenkins) Jason McDonald was also in the wars Awaiting the restart Next time around it would all kick off between these two As well as taking on the Fegans Guinchy put Wittsy in the fence with a monster of a hit. Jack expresses his views on the matter. The heavily re-arranged 880 car is carried off 16 damage Lewis Burgoyne was a fellow Scot with repairs to do Porta power on NI918 The 880 pit drew a crowd to see if any parts of the car were NOT damaged The car needed forklifting on to the trailer It had been a very entertaining weekend for sure! More pics in the gallery Andy Smith's weekend report: WF weekend report part 1. The dust has now settled on what was a superb F2 stockcar World Final over at Nutts Corner Northern Ireland. We set off last Wednesday evening for the long 9 ish hour journey to the Port of Cairnryan Scotland. The journey was easy enough as there were 3 of us sharing the driving although I must admit that upon entering Scotland the 99 more miles on a winding A road were a bit tiring. We sailed over on the Thursday morning and arrived in Belfast to truly awful weather hoping that wasn’t a sign of how the weekend would be. We needn’t have worried as by Friday afternoon all the bad stuff cleared. Once we got settled on the campsite near the track, around 1/2 hour out of Belfast up a really big mountain, me Lisa and the girls taxied down into Belfast to meet up with Team Fisher 315. Take us to the best pub that sells the best Guinness was the order and it didn’t disappoint. We had a great day drinking, eating and laughing. Just what was needed before the serious stuff. Friday was practice day so we headed to the track arriving early afternoon. Upon arrival the pits were already filling up with the many visiting drivers, most of whom like us had never seen the place before. The stadium although basic was well presented and the track looked a good stockcar track. It looked a bit rough but fast and not so wide with an unforgiving concrete wall. I sensed there was going to be some damage! Practice didn’t start well. Both girls last time out in Holland had experienced steering problems and we had bought a lot of new stuff and spent considerable time to try and cure it but Jessica’s was still playing up. Ok in pits but when under load was kicking out. We spent a while swapping even more stuff but to no avail and it was spoiling her runs. Just as we are seriously head scratching Rebecca came off with the same problem developing. FFS! Anyhow, we eventually found something and finally cured Jessica’s. What do they say about the simple things first . We altered the exact same thing on Rebecca’s and bingo both seemed cured but we’d wasted a lot of time. The rest of the practice went “just OK”. Although the girls were getting used to the track neither were fully happy. Jess was quick enough but the car was loose mid turn and despite trying quite a few things we never quite cured it. Rebecca’s car seemed inconsistent in the brake department. We messed around a bit with pads and stuff but the balance still seemed to shift throughout a run and was off putting. So come the end we’d had plenty of time tbh but we weren’t quite there so we’d have to give it some thought and adjust some things overnight. Luckily both girls would have further practice sessions on Saturday. Jess wouldn’t have long though as her timed session was for World Final qualifiers only and with the pre-race scrutineering being much more in depth than usual all the cars had to be done quite early in the day as they were going to form a dummy grid on the track before the meeting started. This is a nice idea and has become a regular feature of the WF in recent years. They open the track to the fans for the “Grid Walk “ where they can chat to the drivers and have photos taken, collect autographs etc. It makes the qualified drivers feel that bit more special as well as being great for the fans especially the kids . Incidentally it’s not a new thing. I remember back in 2008 at the Ipswich WF (which I won by the way ) they did similar although as I remember the promoter of the event squeezed the pips shall we say by charging the fans extra for the privilege! After a few changes Saturday morning Jess went out and yet again the car wasn’t too great and we were running out of time as we were being called to scrutineering. We made a big swing at a change and she would have to hope for the best in the WF. We had done some bracket alterations on Rebecca’s in the hope it would solve her re- occurring brake issues and it seemed to make it a lot better and by the end of the practice she was happy enough. Once the Grid Walk was over the WF cars inc. Jessica’s were pushed off the track into “Parc Ferme” where they couldn’t be touched until they rolled out for the Big Race parade which was scheduled for Race 5. It was now time for the meeting to start with the “Last Chance” race where all of the unsuccessful semi-finalists, along with the local Irish drivers who weren’t directly seeded in would go bunched grid to fight for 6 spots on the back of the WF grid. Rebecca was 3rd row outside. Not the best position in a bunched grid where a big push was inevitable. Could she do it and create history by having both sisters on the WF grid for the first time. This had been hyped quite a bit by the promotional arms of the sport and did put added pressure on her. We would see and find out in Part 2 Part 2 You didn’t have to wait too long . So 1st race up of the evening was The Last Chance. Unfortunately this couldn’t have gone much worse. As the green dropped Rebecca was totally boxed in on the outside down the home straight. As they came into turn 1 she saw a slight gap and gunned it around the outside. She so nearly got away with it just getting tagged on the back corner, turning her round and she got battered by the pack, ending up stranded in the middle of the track. A huge disappointment for her as she really couldn’t have done anything else. She was all OK but will have to try again next year. As this was an extra race we had to get to it to mend it as she was in the supporting heat. There was suspension damage to both front corners (a theme that would continue) and the rear bumper was wrapped around into the wheel. With some help from several other teams we just managed to get her out and we were thankful they held the gate. Our next door neighbour’s, the Bradford Ministox team were kind enough to let us use their welder but we were so rushed I made the call to send her out without a back bumper stay which was risky but better than straight to what would be a very busy consolation. She came in a steady 7th. The car was a bit lame but she was straight through to the meeting final Back in the pits I set to finishing mending the damage and adjusting all the hastily repaired front end bits back to summat like correct. I just managed to get trackside to see our Jess enter the arena with her introduction getting a huge cheer from the big crowd followed by an equally appreciative parade lap. I believe people really commended her efforts to get on the grid. There’s a reason it’s been a full 30 years since Sarah Bowden was the last female driver to do this, that’s because it’s a seriously hard task. I’ve always told my girls they are the same weight in a stockcar as any man so go out there and do it. However, it’s not the same. The physical challenges are much greater to overcome for the females and all the current girls out there holding their own in stockcar racing deserve immense respect and credit . So that reception was enough for me . I have to say at this point what a great atmosphere I thought there was about the place. The announcer was on point and the sound system really good. The flame throwers on the middle were great and the whole choreography of the intros with all the cars lined up opposite the entrance herring bone style was brilliant (take a bow Mr Blackwell). It must have been cool for Dave Polley to come out last in front of that! Onto the race then and Sarah had travelled over to watch and came up to Jess to give her a pep talk (class that, thanks Sarah ) Her advice was just keep going and finish! Well I think she listened because after the green dropped all hell broke loose into turn 1 just behind the first 2 rows who had gotten away clean. They all piled in and Jess backed off early and managed to weave her way through undamaged and a complete restart was called. I think around 8 cars were out so on the restart she was bumped up to row 10 inside from 13. The next restart they got away clean and Jess was too cautious really and dropped a couple of places as it was busy but got up to speed eventually. A few laps in and she couldn’t avoid a spinning car but made sure she hit it correctly and not on the wheels so it didn’t slow her massively. She got going again but by then Gordon 7 was coming around to lap her so she backed off and moved over so as not to hold him up. She finally then found some rhythm and spent the next probably 4 laps circulating between Gordon and Guinch 183 in 2nd place. He was hitting everything he came across hard maybe to get a yellow I dunno but as he slowly caught Jess I hoped she wasn’t going to cop it. She didn’t and she let the lead pack through and carried on an untroubled race to the finish but finish she did. She was outside the top 10 but half the field didn’t make it and she did thus becoming the first female driver ever to do so in the 60 year history of the sport. I was so proud of her especially as the car hasn’t been great lately and the rubbish she’s had to put up with this year meaning her confidence and morale wasn’t exactly high. So this meant she was in the consolation and from the word go I could see she had gained confidence. By now it was dark and the floodlights although sufficient weren’t great but boy did it make the cars look fast. I know she’s dropped to yellow and she should be winning from there but she had local yellow grader Declan McFerran on her tail the whole race and she never put a foot wrong to eventually ease away to victory. The crowd loved it and just to win a race on WF night is special So both girls lined up together for the first time for the feature final of the night. At this point the night took a down turn when as the cars were on the track it became apparent a serious incident had occurred outside the stadium. The track paramedics were in attendance so unfortunately the meeting was abandoned. Such a shame but unavoidable. The decision was made to run the final first race up on the Sunday as an extra race. Onto Sunday then and what a race for us the final turned out to be. Talk about it all come crashing down! Both girls set off clean and it wasn’t long before they were in 1st and 2nd with Rebecca leading the way and going along nicely. As the laps ticked on Rebecca was getting faster and began pulling away from her sister. After more spring changes overnight her car was really fast. 2 weeks ago in Holland she was in the same position but lost it through being to cautious with back markers. Well she learned from it because this time she leathered them out of the way at every opportunity wasting no time. It was great to watch and as the boards were out she was away and it was as good as in the bag. Her sister was hanging on well in 3rd when with 3 to go just as some oil went down 4th place hit Jess sending her hard into the wall, bouncing straight out into the middle of the track with no steering. She tried to move but couldn’t. She didn’t want the yellow but rightly they threw it as she was in a bad place. I couldn’t believe it. 2 to go when one of my girls had it in the bag only for it to be stopped for the other! So 2 lap restart it was and all the back markers removed so she had a train of blues and reds behind her. Chances are she’d be shoved out and drop like a stone but she did great. She got dropped down to 4th but got herself back up to 2nd just being pipped over the line and finishing on the podium in 3rd. Boy was she going to be fuming back in the pits! So that was technically WF night over and all in all it was a great night for our team. History was made but i couldn’t help but rue Rebecca’s luck in that final. It was an excellent meeting spoilt a little by it not being completed on the night but big credit to Ian Thompson and his team for putting a show on. A superb World Champion in Gordon Moodie 7. As I’ve said before the way the guy races oozes class and yet again he beats all before him. A massive well done from us. Also, I have to give a mention to the guy who finished 3rd. The young Irishman Shea Fegan 918. Now in the run up to this World Final people were disrespecting the Irish drivers saying they weren’t good enough, they can’t race when there is loads of cars as their scene is a little down right now. Now I don’t like disrespect to drivers in anyway so I was so pleased for him to shut the critics up and put it on the podium. He also won the meeting final sticking Jess in along the way to get the yellow but I know he didn’t mean it to turn out that way. He’s good pals with the girls. He was driver of the day for me So I’m gonna leave it there for now. I will try and give a run down soon on the Sunday’s events but we are all off to Northampton tomorrow for the F1 world where we will be cheering on The Wild Child to retain his title. Might see you there Section 2: Out and About – Burdale Tunnel We’re heading to North Yorkshire for our main event folks. Our location Burdale Tunnel A railway between Malton & Driffield was first proposed in 1845 as the Newcastle-upon-Tyne and Hull Direct Railway but within days it became the less cumbersome Malton & Driffield Junction Railway. The line of the railway It was clear from the outset that the line would only prove successful if it opened after the completion of the Thirsk – Malton line which was being promoted by George Hudson’s York & North Midland Railway (YNMR). John Birkinshaw and Alfred Dickens (younger brother of Charles Dickens) were appointed to build the line; Birkinshaw had previous experience in railway engineering and was a pupil of Robert Stephenson. The 20 mile Malton & Driffield Junction Railway received its Act on 26th June 1846 and although the route was quickly surveyed it was decided to delay construction until work had started on the Thirsk line. By 1847 there was no progress on the Thirsk line so work started at the southern end of the M&DR and on the Burdale Tunnel which was just under a mile in length and the only major engineering feature on the line. The company quickly ran into financial difficulty as the ‘railway mania’ that had been gripping the country was in decline and share capital proved difficult to find with predicted costs already exceeded. Construction was suspended once sufficient work had been done on the tunnel to prevent flooding. By 1849, the M&DR were verging on bankruptcy and the company approached YNMR Chairman George Hudson for finance. Hudson had previously bought £40,000 worth of unauthorised M&DR shares but was in financial difficulty himself by this time and was unable to help; he was soon forced to resign as chairman of the YNMR. Work on the line restarted in 1850 with savings being made on the construction by shortening the route by running at a higher level with steeper gradients and downgrading the line to single track throughout (the southern portal of the tunnel had been built for two tracks but the northern portal was only wide enough for one) which meant that the original plan to use the line as a trunk route between Hull and Newcastle would have to be abandoned. Work on the Thirsk to Malton line had still not started despite promises to build the line and it was suggested that the M&DR should take over construction but, instead, a writ was served on the Newcastle & Berwick Railway, now responsible for building the line to force them to start work. A new Thirsk & Malton Railway Bill was put before parliament and on 18th October 1851 construction finally started. Progress on the two lines was now rapid and they were both completed in 1853 and officially opened on 19th May. The first train carrying shareholders and invited guests covered both lines running from Pilmoor (the junction with the York – Darlington main line) through Malton to Driffield and then back to Malton. Following the official opening there was a Board of Trade inspection that required some changes which were quickly made with the line opening to passenger traffic on 1st June 1853 with intermediate stations at Settrington, North Grimston, Wharram, Burdale, Fimber (later Sledmere & Fimber) Wetwang and Garton. It was planned that the T & M line should open on the same day but this was delayed following objections by the Board of Trade and the line opened on 7th June or shortly after that date. From the outset, the line was worked by the York & North Midland Railway who amalgamated with the York, Newcastle & Berwick Railway and the Leeds Northern Railway on 31st July 1854 to form the North Eastern Railway. The M&DR also applied to join the new company which it did on 28th October 1854 with one director out of a total of 17 NER board members. The new line left the Scarborough line 1/4 east of Malton running parallel on double tracks for a further 1/4 of a mile before branching to the east to reach Scarborough Junction, the junction with the Thirsk & Malton line. From this point the line was single track, with a rarely used passing place at Wharram, to a junction with the Hull – Bridlington branch of the YNMR 1/4 mile south of Driffield station. All the stations were provided with single short low platforms which were raised in the c. mid 1890s. The passenger service, known locally as the ‘Malton Dodger’, remained much the same throughout the line’s life with three daily return trips from Malton with a fourth train being added during some seasons, and additional trains to cater for market days at Malton and Driffield; there was also a daily pick-up goods train from Malton. The journey time was between 50 – 60 minutes with most trains consisting of two carriages hauled by a small tank engine from the Malton shed. Occasionally horse boxes and carriage trucks (flat trucks for the conveyance of carriages for the local gentry) were attached to passenger trains. Between the wars there were some additional scenic excursions where the trains stopped longer at some of the stations for passengers to view the station gardens. In later years the line was sometimes used by holiday specials from Scotland and the North East serving Scarborough (requiring a double reversal at Malton) and Butlin’s Filey Holiday Camp. Regular coal trains served coal drops located at each of the stations and livestock trains ran when required, usually on market days. Initially most of the freight traffic was agricultural including manure and fertilisers inbound, arable crops outbound. Sometime in the 1800s a small limestone quarry at Settrington generated business, this quarry closed around the turn of the century. Later the quarry trade became important, the first big quarry to ship limestone was at North Grimston; by the mid 1920s this quarry was shipping about 28,000 tons of limestone per annum. The owners of North Grimston later moved their operation to Burdale. The next quarry to open was at Wharram and this generated a significant output of chalk during the 1920s. Wharram quarry closed in the early 1930s but a little later re-opened under new management but at a greatly reduced output. The final big quarry, and the largest of them all, was at Burdale. This opened in 1925 but the operation was much less mechanised than Wharram. The output of Burdale peaked in the late 40s/early 50s with annual shipments of about 50,000 tons. Burdale Quarry Passenger traffic was at its peak just before WW1 but the M&DR always remained one of the less profitable lines on the NER. After WW1 the line came under the control of the London & North Eastern Railway under the general grouping on 1st January 1923. Fares immediately rose and passenger numbers began to suffer as buses reached the Yorkshire Wolds in 1924. Buses ran right into village centres while many of the stations were sited some distance from the villages they served. The General Strike of 1926 and the coal shortage that followed further damaged the railway with an emergency service of two daily trains running between Driffield and Malton and it wasn’t long before local station closures were announced due to increasing road competition. Intermediate stations between Scarborough and York were closed on 22nd September 1930 leaving only Malton and Seamer open. The Malton – Gilling service was next to go, closing to passengers on 1st January 1931. Surprisingly the Malton & Driffield line survived these early cuts, perhaps because there was no suitable parallel road. Road competition also affected agricultural freight traffic although all the stations closed to passenger traffic remained open for freight and the Malton & Driffield was actually at its busiest between the wars carrying stone from the local quarries. During WW2, the line was regularly used by troop trains and for transporting munitions to the many airfields in the East Riding and at one time sentries were posted at both ends of the Burdale tunnel to prevent sabotage. All station signage was removed in 1940. The railways were nationalised on 1st January 1948 with the M&DR coming under the control of British Railways North Eastern Region. Initially the pre-war service of three daily passenger trains and a pick-up goods train was reinstated. For the first time the line was used regularly by long distance passenger trains with the resumption of the summer Saturday holiday trains from the north east and Scotland but with the ever increasing popularity of road transport this was to be short lived and the passenger service was withdrawn from 5th June 1950 with the last train running on 3rd June; this train was packed. The line was temporarily reopened to passengers between 12-16th February 1953 due to bad weather. Potential customers were informed of the opening on the previous evening’s news. It is not known if all the stations were used. The line remained open for freight and passenger excursions but the pick-up goods service was reduced to Tuesdays and Thursdays with a short running to Sledmere & Fimber on Saturdays. The platforms at some of the stations were shortened to serve the goods trains. Despite Burdale quarry reaching its peak after the war, it closed in 1955 with the loss of the last regular freight traffic on the line. With the quarry closure it was no longer necessary to keep the line open although in the hard winter of 1957/8 when much of the Wolds were cut off by snow a special passenger and goods service was again introduced over the line. Two enthusiasts’ specials ran in 1957, the first on 02/06/57 and organised by the Branch Line Society, and the second being organised by the RCTS and running on 23/06/57. Final closure came on 20th October 1958 although the last goods train ran on 16th October, the very last train along the line running on 18th October. Most of the track was lifted shortly after closure and sold for scrap with the exception of a short stub left at Malton to provide access to the bacon factory at Norton and to serve the Thirsk & Malton line until 10th August 1964. At the Driffield end, the double track section from Driffield West was still in use for trains to/from the Market Weighton direction until 14th June 1965. This tunnel through the Wolds is 140 yards longer than originally planned, falling short of a mile by just 16 yards. In 1845 it was anticipated that the tunnel would be through dry chalk; in the event 2/3rds of it where through severely unstable shale. Work started in 1847 from its southern end and working faces either side of four construction shafts but in a little over a year only 150 yards had been cut. Difficulties were experienced with flooding and rockfalls. The southern end was constructed as an elaborate (and huge) double track portal with magnificent stone work. The width for double track continues for around 30 yards. The northern end is of a much plainer (although practical) red brick construction and built only for single track. The tunnel bore shrinks 30 yards beyond the entrance but opens out again at several locations. Eight 9-foot diameter shafts were eventually dug to aid construction, three being retained for ventilation purposes. The tunnel’s operational history was chequered. On 21st August 1866, a labourer fell from a carriage as it headed south through the bore. He survived, albeit with serious injuries to his face, head and elbow. After receiving pain relief in Malton, he was taken to Driffield Cottage Hospital where doctors amputated his arm. A guard smashed his head on a bridge at the northern end whilst riding on the tender. Soon after closure, several stories exist of people driving, biking and even walking through the tunnel. There are even stories of tiddlywinks being played half-way through. The game being lit by the headlights of cars. To prevent this kind of activity the tunnel was bricked up at both ends to prevent people entering in July 1961. In the late Seventies, a collapse occurred just north of the tunnel’s second ventilation shaft – around half-a-mile in. The mid-80s saw another fall block the tunnel towards its southern end, creating a sealed section in the middle. Flooding and landslips were commonplace, and even today, the entire area around the Wharram end is totally waterlogged. After long periods of rainfall, water levels in the tunnel can reach depths of 12 feet. (Credit to Nick Catford for the above information) The pics: The track bed can be seen heading past Burdale Quarry to the tunnel which is in the left corner. The green expanse curving to the right is Fairy Dale. Notice the two platelayers huts on the hillside. On a 1914 map Tunnel Cottage is shown A number of years ago - A family walking along the track bed. Burdale tunnel is in the distance with Tunnel Cottage visible in the middle of the picture. The plate layers huts can also be seen on the hillside to the right. Burdale quarry is to the right behind the camera. Still there today Fairy Dale A chalk spoil tip The tunnel comes into view The tunnel had a hut just outside of each of its portals. This one is on the southern side and has long since disappeared The remains of the hut today A RCTS Railtour special leaves the southern portal of the tunnel Disused but with the rails still in situ The southern portal is finally bricked up In 2023 Built to last We’re in The last bit of natural light for a while An open tunnel drain has a good flow of water through it The tunnel roof castings have survived Stone and brick construction. Notice how the tunnel bore decreases further in. Blue engineering brick and the remains of two porcelain insulators Looking up one of the ventilation shafts Further along another work of art Unfortunately it is not long before we come to the start of the collapse Massive pieces of the tunnel lining have broken away We are soon left with a total separation of the brick lining Moving further through there are numerous fractures in the tunnel roof This is the limit of our pass through. It is only a crawl from here and if this lot comes down we are all done for! Back outside now looking south from the portal We’ll make our way north through Tunnel Plantation which is over the top of the tunnel. There are the air shafts to see here. The first has a grille over the top of the small tower This lower one has been capped with concrete The next one is fenced off for good reason The vent shaft has dropped into the void below as we are above the collapsed section at this point. A thin covering of overgrowth and tree cover conceals a drop into the abyss. At the north portal. After heavy rain water rises to the height of the yellow label on the door and pours into the tunnel through the missing brick. A tender first 64947 on a goods run on the final approach to the north portal of Burdale Tunnel In 1954, three J39s, numbered 64867, 64928 and 64947 were allocated to Malton Shed. These were chiefly employed on the Burdale to Malton, and Malton to Thirsk goods trains conveying stone for use at various blast furnaces in the Middlesbrough area. The west end of Malton engine shed in 1955, with BR J39 64867 outside and 64928 inside The track bed curves away to the north. This resembles a canal in winter with water up to the top of the banks. The northern portal and hut can be clearly seen in this superb photo With the railway gone it was up to the local bus service to move people around. Seen heading for Malton in NBC days, 1973 Bristol LH6L United 1558 is near the end of its life. It was withdrawn and scrapped in September 1982, just nine years old. We leave the tunnel behind now and head for our second location which is only minutes away. We’ll have a look at that next time. Odds and Ends The Leyland Gathering 2023 The annual gathering of all things Leyland took place at the Buckingham Railway Centre, Quainton. Here are the photos from a great day: Leyland Tiger PS1 new in April 1949 London Transport 1936 Leyland Cub SKPZ2 Park Royal RC18F New to London Transport for interstation use with fleet number C111 in what used to be called an ‘observation coach’ style. UOU 419H Leyland Panther Fleet Number: 419 Year: 1970 Chassis: Leyland Panther PSUR1A/1R Engine: Leyland 0.680 Body: Plaxton Derwent B52F The last of the three Leyland Panthers bought by King Alfred Motor Services in 1970 for £7,300 each. It operated with Hants and Dorset following the demise of King Alfred Motor Services in April 1973 until withdrawal in 1980. Sold to Rees and Williams of Tycroes, south Wales, 419 was eventually bought by the Friends of King Alfred Buses in 1988 and returned to King Alfred livery. RTW185 was delivered new in 1949 to London Transport's Putney Bridge Garage. In May 1950 it took part in the Nottinghill Gate Test to establish whether RTWs, due to their 6 inch extra width would be suitable for use in Central London. In 1965 it ceased passenger service and became a driver training vehicle at Holloway, Muswell Hill, and finally Clapton. It covered at least one million miles whilst in service. It was the last RTW to be owned by LT. South Notts 82 (82 SVO), a Leyland-badged Albion Lowlander. The first of five Northern Counties-bodied Lowlander LR3s that the Gotham-based independent — part owned by Barton — bought for its services into Nottingham city centre, it was built in 1963. They marked a stepping stone between its purchase of lowbridge side sunken gangway doubledeckers and its first rear-engined Atlanteans. The Lowlander was a lowheight version of the Leyland Titan PD3, built at the Albion Motors works in Glasgow mainly but not exclusively for the Scottish Bus Group. The LR3 combined a synchromesh gearbox with leaf suspension. The immaculate Knowles fleet The livery now 1984 Leyland Atlantean/Northern Counties 1989 Leyland Olympian ECW Leyland Titan H44/24D - 9/1982 New to London Transport (T567) 1929 Leyland Lioness coach was new to White Rose Motor Company of Rhyl North Wales . In 1939 it was bricked up in a tunnel in Jersey to prevent it being used during the German Occupation . It has never been fully restored, only repainted and a few new parts added such as the fold down roof and seating. Leyland Leopard / Marshall Maidstone & District New to Maidstone & District 7/1972 as 3456 East Kent 1948 Leyland Tiger PS1/1 Park Royal C32R South African Express Locomotive 'Janice'. Built in 1954 by the North British Locomotive Company in Glasgow. They were amongst the most technically advanced and powerful steam locomotives ever built in this country. 'Janice' regularly hauled the luxurious Blue Train across South Africa until the late 1970s. CO/CP Stock - This unit consists of converted O stock car 53028 (originally 13028), trailer 013063 and converted P motor car 54233 (originally 14233) that had the most varied life, having been famously rebuilt from two war-damaged cars. These cars would have served the Metropolitan, Hammersmith & City and District Lines during the type’s 43-year service on London Underground. Class 115 DMU Egyptian National Railway Steam Rail car run on Bunker Oil rather than coal - It is one of only ten units built by Sentinel and Metro-Cammell in Birmingham in 1951 Built by Hunslet in 1964 this was the last standard gauge locomotive built in this country for the home market. The loco was part of the South Yorkshire NCB fleet and was sent to Cadeby Main Colliery, Conisborough. The track bed heading north The Brill Tramway Locomotive - One of two built in 1872 by Aveling & Porter of Rochester. It was used on the Wotton Tramway between Quainton Road and Brill. It was adapted from a road traction engine and had a chain drive and flywheel. This 'accident crane' as it was known originally was built by Cowans Sheldon of Carlisle in 1914 and spent most of its life in Harrow goods yard. 'Beattie' was built in 1874 by Beyer Peacock and was one of 85 locos built to serve suburban trains out of Waterloo. 'Hilsea' - The locomotive was built in 1961, one of the last made by Ruston & Hornby of Lincoln. It is fitted with a Ruston 4VPH engine which is started by compressed air from a donkey engine. It spent its life working for British Gas at Hilsea Gasworks near Portsmouth. It is a standard 20ton locomotive and was used to move, separate and unload tanks of naphtha gas. Gas would arrive in 20 ton trucks from the Esso plant at Fawley on the edge of the New Forest. Hibberd diesel shunter A 1961 built Ruston & Hornsby diesel shunter. It was originally ordered by the MOD and was based at Bramley A 1959 Ruston & Hornsby shunter. It worked at a cement works shunting wagons of coal brought in from the Nottinghamshire collieries via the exchange sidings on the branch line between Luton and Dunstable. It would also have marshalled wagons of Presflo Cement ready to be hauled away by British Railways. Homeward bound There were some quality vehicles on display at this event 👍 In the last one for this off season next time we will be definitely going here:

-

4

-