-

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Days Won

184

Everything posted by Roy B

-

Continued from above: Scorched earth The two men extricated themselves from the shattered cockpit and walked along one of the streams until they reached the Hayfield to Glossop road. A passing lorry driver stopped and picked them up and took them to a nearby pub where Lt Houpt telephoned Burtonwood to report the accident. They were then retrieved by an ambulance from Burtonwood and their injuries were then treated. These were mainly cuts & bruises but Lt Houpt did suffer a broken jaw. The undercarriage is still in the flight retracted position within the wing This undercarriage leg and wheel has been thrown clear of the aircraft on impact The split pins inside are like new Part of a fire damaged frame Continues below:

-

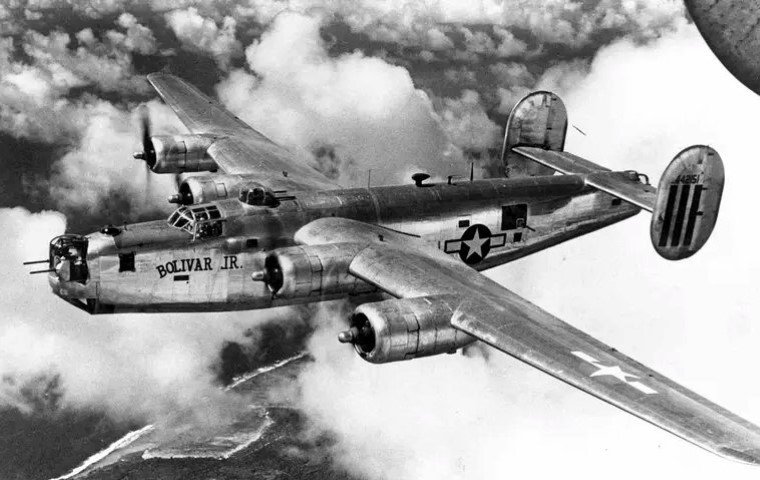

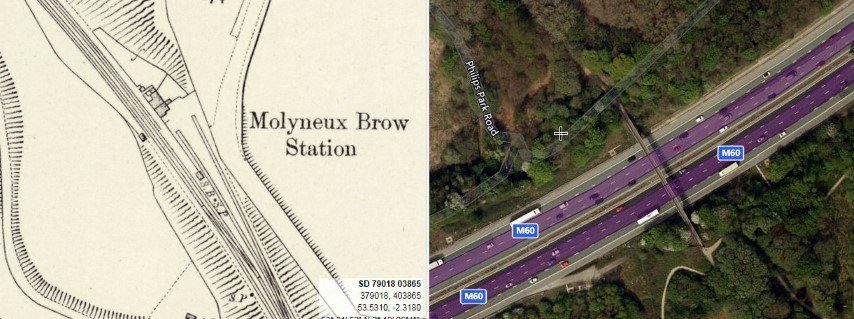

Continued from above: View across the bridge To the platform Peak Rail operate the line and this was once the southern terminus point of all their trains. This station is only used in the event of any operational difficulties with obtaining access to Matlock Platform 2. This station consists of a temporary wooden platform, together with a small waiting shelter. The station is located a good 10-minute walk from the main Matlock Town Centre, access to which is via the footpath alongside the riverbank or by using the A6 by-pass road a short distance from Sainsbury’s store and near to the A6 roundabout. Whether it’s simply a nostalgic journey back to a bygone age or a discovery of the sights and sounds for very first time of a steam or diesel locomotive Peak Rail allows you to experience the thrill of its preserved railway whilst travelling through the delightful Derbyshire countryside. The Midland Railway route linking Derby and Manchester across the Derbyshire Peak District must rate as one of the most spectacular lines ever to have existed in the country. Whatever the merits and claims of other lines, the railway, which carved through Derbyshire’s great limestone hills, has been described as the most scenic line in Britain. Because of the terrain, numerous tunnels and other impressive civil engineering features including the magnificent viaducts at Millers Dale and Monsal Dale had to be constructed. The railway was not conceived as a single entity by one company but was in fact the result of the ambitions of several separate companies who for their own individual reasons, built the line at different times over a period of some 20 years. Nevertheless, the eventual result of these ventures was a mainline providing a direct route between Derby and Manchester. The first section of the route between Derby and Ambergate was opened to traffic on 11th May 1840 as part of the “North Midland Railway” line to Rotherham via Chesterfield. North-westwards from Ambergate to Rowsley was constructed by a company with the lengthy title of the “Manchester, Buxton, Matlock and Midland Junction Railway” (M.B.M. & M.J.R.). June 4th, 1849 was the official opening day of the Ambergate-Rowsley section, with passenger and coal traffic commencing running on 20th August. The original scheme was to build a line from Cheadle to Ambergate with the Manchester and Birmingham Railway and the Midland Railway providing financial support as both companies expected to gain from this link. However, the L.N.W.R. having been formed by an amalgamation of various railway companies, found it had a shareholding in the M.B.M. & M.J.R., a line that it was not interested in as it would be a source of competition. Eventually in 1871 the M.B.M. & M.J.R. was absorbed into the Midland Railway system. Before this date the Midland had already constructed a line from Rowsley to Manchester, although this did not follow the route intended by the M.B.M. & M.J.R. owing to the opposition of the Duke of Devonshire to the idea of a railway through Chatsworth Park. In its efforts to gain a through route to Manchester, the Midland Railway had surveyed several possible routes to achieve this end. A line from Duffield to Rowsley was commenced but was terminated at Wirksworth. One outrageous proposal, however, was the upgrading of the Cromford and High Peak Railway to main line status which would have resulted in Derby-Manchester expresses going over gradients as steep as 1:8. The section of the Rowsley-Manchester line was commenced in September 1860. Heading north from the new Rowsley station was Haddon Hall, ancestral home of the Duke of Rutland. The Duke was unwilling to allow the railway to cross his estate on the surface, so the company was forced to go underground. Haddon Tunnel at 1058 yards is the longest between Matlock and Buxton; it is in fact a covered way being on average only 12 feet deep. A cutting would have sufficed to preserve the view from Haddon Hall, but the Duke did not want to see smoke and steam rising above his stately gardens. (We’ll be having an explore of this majestic tunnel in a future post). The Duke used Bakewell station for boarding and alighting from trains and it was therefore a far grander affair than one would expect of a small market town. His coat-of-arms was built into stonework on the platform façade. The Duke of Devonshire used Hassop station which was 2 miles from the village from which it took its name. The next station along the line towards Buxton was Longstone, later named Great Longstone, which served the occupants of nearby Thornbridge Hall. Heading farther northwards, the railway passes through the 533 yards Headstone Tunnel, and from this the line bursts spectacularly on to Monsal Dale viaduct. The structure has five spans each of 50 feet. Although resented by a few prominent people when built, it now blends perfectly well with the surrounding countryside. The station at Monsal was provided for tourists, as there are very few dwellings in the area. The down platform was cut of the stone hillside while the up platform was built on wooden piles, as the valley is so sheer at this point. Cressbrook and Litton tunnels at 471 yards and 515 yards respectively follow in quick succession. Climbing at 1 in 105, the line reached a summit east of Millers Dale before falling into the station here. Before Millers Dale station is entered, two viaducts stand. The southern-most was built when the line was opened while the northernmost was opened in 1905. Millers Dale was originally two platforms plus a bay for the Buxton branch. When the second viaduct was completed, two platforms were added making a total of five. This might seem, again, to be a very large station for what was only a small hamlet with few inhabitants, but this was because people wishing to travel to the Spa town of Buxton had to change trains at this point. Such was the practice of the Romans for building settlements on the tops of hills, that there was no other means of providing rail communications other than a branch to this important Spa town. However, in recompense the Midland provided a fine station building, which possessed a handsome façade and this, was copied by the L.N.W.R. terminus next door. From Millers Dale innumerable problems were encountered with the next section towards the junction at Peak Forest. With the River Wye occupying the valley floor, three tunnels were constructed, Chee Tor No. 1, Chee Tor No. 2 and Rusher Cutting. Such was the shortage of space at this point; the track bed was hewn into a shelf in the valley side. Moving northwards, the branch to Buxton deviates from the main line to Manchester at Millers Dale Junction. Here the smallest station in Britain was sited at Blackwell Mill Halt. This was built to provide transport for the nearby railway cottages. Only a few trains a week stopped here to enable the wives to collect their shopping from Buxton. From Peak Forest, this line enters Wye Dale and the 191 yards Pic Tor Tunnel and into Ashwood Dale. A further tunnel here exactly 100 yards long brings the line on to Ashwood Dale viaduct and into Buxton Midland Station. 1st January 1923 marked the first major change in the administration of the railways in the Peak District. From that day the railways of England were grouped into four companies. As far as the Peak District was concerned, the lion’s share went to the L.M.S. From a local point of view nothing much changed. Red carriages with gold lettering still formed the Midland expresses. On some occasions, an L.N.W.R. locomotive hauling Midland coaches could be seen, a sight unheard of before 1923 and one that would have virtually caused civil war. The amalgamation meant that competing routes could be rationalised. The two Buxton stations were placed under one stationmaster; the former L.N.W.R. platforms were numbered 1, 2 and 3, and the Midland ones relegated to 4, 5 and 6. Departures for Manchester could be arranged alternately instead of simultaneously, but the longer journey time via Millers Dale resulted in alternate departures from Buxton becoming simultaneous arrivals in Manchester. Throughout its long career, the Peak Line was used by many fast expresses including the “Peak Express”, the “Palatine” and the “Midland Pullman”, providing evidence of the significance of this railway. Impressive locomotives were frequently observed traversing its metals including Samuel Johnson’s superb 4-2-2 express engines, while in later years, Jubilees, Patriots and the occasional Royal Scot handled the heaviest passenger traffic over this steeply graded line. Before the eventual demise of the route, Britannia’s and the Blue Midland Pullman gave glory to the twilight years. Freight traffic was also of great importance throughout its history. Following the demise of the Lancashire coalfields during the inter-war years, much of the coal to power the industry of the north-west had to be transferred across the Peak District from the East Midlands. The increased volume of freight resulted in large numbers of Stanier 2-8-0’s, the large Beyer-Garratts and in later years 9F’s could be seen blasting their way up the inclines with their seemingly endless coal trains. Because of the severe gradients encountered on this line, particularly from Rowsley northwards, banking engines were often required, supplied from Rowsley engine shed, to ensure a clear flow of traffic over the main line. Except for a few short downward stretches, the line from Rowsley climbs at an average of 1 in 100 over its entire length, making life for the engine crews particularly difficult, especially in wintertime when the weather can be extremely severe. From Rowsley the line climbs almost 600 feet on its journey to Buxton. In 1962 came the publication of “The Reshaping of Britain’s Railways”, more commonly called the “Beeching Report”. The recommendations of this weighty volume included the closure of two-thirds of the unprofitable lines, to leave the remaining system to pay its way. The first implementation of the report’s proposals was to be the closure of both Buxton branches to passengers. The protests of the local inhabitants deferred these closures. The closure of the Ambergate-Chinley section began in 1954 when Dove Holes tunnel was found to be unsafe. The line was closed at night in order to carry out repairs and trains never again ran at night over this section. Freight traffic was diverted via Chesterfield before local passenger services ceased in March 1967, with the closure of the following stations: Millers Dale, Bakewell, Rowsley, Darley Dale and Matlock Bath. However, through trains from St. Pancras to Manchester continued for another year. Since that time trains still run as far as Matlock and freight trains travel along Ashwood Dale from quarries in the Peak Forest area. When in 1968 the last of the direct St. Pancras-Manchester express service was transferred away from the Peak Line and the track quickly lifted, it seemed like the days of rail access to the Peak District had gone forever. Rail enthusiasts on their own initiative got together to form the “Peak Railway Society”. After an initial meeting, membership quickly grew to over a thousand people and then later a commercial operating company “Peak Rail Operations” was formed with the aim of restoring the Peak Line for recreational and community use. The long uphill struggle then began to convince local authorities of the viability of restoring and maintaining a 20-mile railway. Shops were opened at Buxton and Matlock and members attended many fund-raising and publicity events to inform the public of the society’s aims. In 1981 the former Buxton Midland site was purchased and turned from what was derelict ground into a thriving Steam Centre. In 1986 P.R.S. and P.R.O. merged to form Peak Rail Limited to provide a more co-ordinated approach with a tighter management structure. Eventually in 1987 a special local authorities joint working party agreed to recommend to their respective constituent authorities’ acceptance of Peak Rails “Fifteen year Financial and Operating Plan”. This comprehensive document detailed the phased plan for reconstruction and operation of the railway identifying sources of finance, method reconstruction, analysis of potential business markets and the pattern of services, with due regard to environmental protection. October 1988 saw the successful launch of the first major share issue converting P.R.L. into “Peak Rail plc”. The proceeds of this issue were used to fund the rebuilding of the railway from Darley Dale to Matlock (Riverside) which opened to public services in 1992. Insufficient finance delayed further construction so the Buxton Steam Centre was closed, and parts of the land sold, which allowed building to continue northwards. A second share issue provided the funding required to reach Rowsley (South) in 1997 and allowed the redevelopment of the former Rowsley engine shed site. Following some years of consolidation Peak Rail has prospered and completed its southern objectives in 2011, when the major redevelopment of the former Cawdor Quarry in Matlock allowed the railway to extend its services into Matlock Station giving Peak Rail a town centre terminus and a cross platform link with the national rail service. However, the ambition to complete the re-opening of the railway through the Peak District National Park to Buxton remains alive. Consequently, Peak Rail is currently in discussions with various commercial interests, together with the relevant national and local authorities about the possibilities of re-opening the railway as a freight diversionary route which would allow Peak Rail to extend its services northwards. The lines rich railway history, together with the prospect of again being able to travel through magnificent scenery on a railway linking some of Derbyshire’s principal tourist centres, ensures that the desire to fully re-open the railway will never diminish. Pics in the gallery The B-24 Liberator on Kinder Scout Our next stop is a layby on the highest point of the A57 between Sheffield and Glossop. The Pennine Way crosses here and we are going to get the walking boots on and head south along the flagstones that have been laid across this wild moorland. The flagstone’s earlier lives were spent on the floor of the West Pennine mills of the Industrial Revolution. They were destined to be broken up as waste but instead were lifted, packed in crates and flown by helicopter to the Pennine Way. The large rectangular slabs of Bacup sandstone were placed rough side (underside) upwards in order to give maximum grip to walkers’ boots. Laid directly onto the ground, in effect they float on the soft peat as their size spreads the surface area loading. As far as possible they were laid in gentle curves, following natural undulations and contours, and so avoided artificially straight lines. Since the stones were recycled, they already had 150 years of weathering and didn’t have the look of newly quarried material. Some still had drilled holes that were once used as the footings of looms. The stone was originally cut from the Pennine hills and was now laid to rest in those very same hills. It has gone full circle. The mill workers looked to escape the weekday drudgery by walking in the same hills; when they finally achieved decent access people were able to walk for leisure, and some of the moorland paths became eroded. Repairs were needed. When the mills closed down the redundant stone was returned to the hills to form durable and lasting pathways. How neat is that? We are on the lookout for the remains of a B-24 Liberator that came down here nearly eighty years ago. First though we’ll have a look at the marque’s story: The Consolidated B-24 Liberator was an American heavy bomber that entered service in 1941. A highly modern aircraft for its day, it first saw combat operations with the Royal Air Force. With the American entry into World War II, production of the B-24 increased. By the end of the conflict, over 18,500 B-24s had been constructed making it the most-produced heavy bomber in history. Employed in all theatres by the US Army Air Forces and US Navy, the Liberator routinely served alongside the more rugged Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress. In addition to service as a heavy bomber, the B-24 played a critical role as a maritime patrol aircraft and aided in closing the "air gap" during the Battle of the Atlantic. The type was later evolved into the PB4Y Privateer maritime patrol aircraft. Liberators also served as long-range transports under the designation C-87 Liberator Express. Origins In 1938, the United States Army Air Corps approached Consolidated Aircraft about producing the new Boeing B-17 bomber under license as part of the "Project A" program to expand American industrial capacity. Visiting the Boeing plant in Seattle, Consolidated president Reuben Fleet assessed the B-17 and decided that a more modern aircraft could be designed using existing technology. Subsequent discussions led to the issuing of USAAC Specification C-212. Intended from the outset to be fulfilled by Consolidated's new effort, the specification called for a bomber with a higher speed and ceiling, as well as a greater range than the B-17. Responding in January 1939, the company incorporated several innovations from other projects into the final design which it designated the Model 32. Design & Development Assigning the project to chief designer Isaac M. Laddon, Consolidated created a high-wing monoplane that featured a deep fuselage with large bomb-bays and retracting bomb-bay doors. Powered by four Pratt & Whitney R1830 twin Wasp engines turning three-bladed variable-pitch propellers, the new aircraft featured long wings to improve performance at high altitude and increase payload. The high aspect ratio Davis wing employed in the design also allowed it to have a relatively high speed and extended range. This latter trait was gained due to the wings thickness which provided additional space for fuel tanks. In addition, the wings possessed other technological improvements such as laminated leading edges. Impressed with the design, the USAAC awarded Consolidated a contract to build a prototype on March 30, 1939. Dubbed the XB-24, the prototype first flew on December 29, 1939. Pleased with the prototype's performance, the USAAC moved the B-24 into production the following year. A distinctive aircraft, the B-24 featured a twin tail and rudder assembly as well as flat, slab-sided fuselage. This latter characteristic earned it the name "Flying Boxcar" with many of its crews. The B-24 was also the first American heavy bomber to utilize tricycle landing gear. Like the B-17, the B-24 possessed a wide array of defensive guns mounted in top, nose, tail, and belly turrets. Capable of carrying 8,000 lbs. of bombs, the bomb-bay was divided in two by a narrow catwalk that was universally disliked by air crews but served as the fuselage's structural keel beam. B-24 Liberator - Specifications (B-24J): General Length: 67 ft. 8 in. Wingspan: 110 ft. Height: 18 ft. Wing Area: 1,048 sq. ft. Empty Weight: 36,500 lbs. Loaded Weight: 55,000 lbs. Crew: 7-10 Performance Power Plant: 4 × Pratt & Whitney R-1830 turbo-supercharged radial engines, 1,200 hp each Combat Radius: 2,100 miles Max Speed: 290 mph Ceiling: 28,000 ft. Armament Guns: 10 × .50 in. M2 Browning machine guns Bombs: 2,700-8,000 lbs. depending on range An Evolving Airframe An anticipated aircraft, both the Royal and French Air Forces placed orders through the Anglo-French Purchasing Board before the prototype had even flown. The initial production batch of B-24As was completed in 1941, with many being sold directly to the Royal Air Force including those originally meant for France. Sent to Britain, where the bomber was dubbed "Liberator," the RAF soon found that they were unsuitable for combat over Europe as they had insufficient defensive armament and lacked self-sealing fuel tanks. Due to the aircraft's heavy payload and long range, the British converted these aircraft for use in maritime patrols and as long range transports. Learning from these issues, Consolidated improved the design and the first major American production model was the B-24C which also included improved Pratt & Whitney engines. In 1940, Consolidated again revised the aircraft and produced the B-24D. The first major variant of the Liberator, the B-24D quickly amassed orders for 2,738 aircraft. Overwhelming Consolidated's production capabilities, the company vastly expanded its San Diego, CA factory and built a new facility outside of Fort Worth, TX. At maximum production, the aircraft was built at five different plants across the United States and under license by North American (Grand Prairie, TX), Douglas (Tulsa, OK), and Ford (Willow Run, MI). The latter built a massive plant at Willow Run, MI that, at its peak (August 1944), was producing one aircraft per hour and ultimately built around half of all Liberators. Revised and improved several times throughout World War II, the final variant, the B-24M, ended production on May 31, 1945. Other Uses In addition to its use as a bomber, the B-24 airframe was also the basis for the C-87 Liberator Express cargo plane and the PB4Y Privateer maritime patrol aircraft. Though based on the B-24, the PBY4 featured a single tail fin as opposed to the distinctive twin tail arrangement. This design was later tested on the B-24N variant and engineers found that it improved handling. Though an order for 5,000 B-24Ns was placed in 1945, it was cancelled a short time later when the war ended. Due to the B-24's range and payload capabilities, it was able to perform well in the maritime role, however the C-87 proved less successful as the aircraft had difficulty landing with heavy loads. As a result, it was phased out as the C-54 Skymaster became available. Though less effective in this role, the C-87 fulfilled a vital need early in the war for transports capable of flying long distances at high altitude and saw service in many theatres including flying the Hump from India to China. All told, 18,188 B-24s of all types were built making it the most produced bomber of World War II. Operational History The Liberator first saw combat action with the RAF in 1941, however due to their unsuitability they were reassigned to RAF Coastal Command and transport duty. Improved RAF Liberator IIs, featuring self-sealing fuel tanks and powered turrets, flew the type's first bombing missions in early 1942, launching from bases in the Middle East. Though Liberators continued to fly for the RAF throughout the war, they were not employed for strategic bombing over Europe. With the US entry into World War II, the B-24 began to see extensive combat service. The first US bombing mission was a failed attack on Wake Island on June 6, 1942. Six days later, a small raid from Egypt was launched against the Ploesti oil fields in Romania. As US bomber squadrons deployed, the B-24 became the standard American heavy bomber in the Pacific Theatre due to its longer range, while a mix of B-17 and B-24 units were sent to Europe. Operating over Europe, the B-24 became one of the principal aircraft employed in the Allies' Combined Bomber Offensive against Germany. Flying as part of the Eighth Air Force in England and the Ninth and Fifteenth Air Forces in the Mediterranean, B-24’s repeatedly pounded targets across Axis-controlled Europe. On August 1, 1943, 177 B-24’s launched a famous raid against Ploesti as part of Operation Tidal Wave. Departing from bases in Africa, the B-24’s struck the oil fields from low altitude but lost 53 aircraft in the process. Battle of the Atlantic While many B-24’s were hitting targets in Europe, others were playing a key role in winning the Battle of the Atlantic. Flying initially from bases in Britain and Iceland, and later the Azores and the Caribbean, VLR (Very Long Range) Liberators played a decisive role in closing the "air gap" in the middle of the Atlantic and defeating the German U-boat threat. Utilizing radar and Leigh lights to locate the enemy, B-24’s were credited in the sinking of 93 U-boats. The aircraft also saw extensive maritime service in the Pacific where B-24’s and its derivative, the PB4Y-1, wreaked havoc on Japanese shipping. During the course of the conflict, modified B-24’s also service as electronic warfare platforms as well as flew clandestine missions for the Office of Strategic Services. Crew Issues While a workhorse of the Allied bombing effort, the B-24 was not hugely popular with American air crews who preferred the more rugged B-17. Among the issues with the B-24 was its inability to sustain heavy damage and remain aloft. The wings in particular proved vulnerable to enemy fire and if hit in critical areas could give way completely. It was not uncommon to see a B-24 falling from the sky with its wings folded upwards like a butterfly. Also, the aircraft proved highly susceptible to fires as many of the fuel tanks were mounted in the upper parts of the fuselage. In addition, crews nicknamed the B-24 the "Flying Coffin" as it possessed only one exit which was located near the tail of the aircraft. This made it difficult to impossible for the flight crew to escape a crippled B-24. It was due to these issues and the emergence of the Boeing B-29 Superfortress in 1944, that the B-24 Liberator was retired as a bomber at the end of hostilities. The PB4Y-2 Privateer, a fully navalized derivative of the B-24, remained in service with the US Navy until 1952, and with the US Coast Guard until 1958. The aircraft was also used in aerial firefighting through 2002 when a crash led to all remaining Privateers being grounded. Our particular aircraft was B-24J Liberator 42-52003 of the 310th Ferry Squadron, 27th Air Transport Group which crashed on Mill Hill after a shaky take off. We need to search this area! The aircraft was being ferried from Burtonwood to Hardwick by a two man ferry crew on the 11th October 1944. This was a brand new B24 on its delivery flight. It took three attempts to get off the ground and was damaged in the process. The two men took off from Burtonwood, near Warrington at 10:32. They set a course of 135 degrees and climbed to an indicated altitude of 2800 feet. At approximately 10:45 while in cloud and moderate to severe turbulence the pilot Lt Houpt spotted a small gap in the cloud and saw the ground was only about 150 feet below him. He then applied full power and began to climb, but before they could gain any meaningful height the aircraft struck the ground on Mill Hill some 1.5 miles from the Grouse Inn between Hayfield and Glossop. The crash site located Continues below:

-

Continued from above: Defending title holder was Steven Gilbert (542) who took his first ever Final win at Mendips with the last running of the Pink Ribbon. However, the Cornishman was not going to be taking part as he was serving a ban for misdemeanours at Taunton earlier in the month. After a busy period of race action, with the July Speedweekend’s, and championships getting redistributed it was an opportunity to ‘come home’ for the West Country superstars. Jon Palmer (24) would be looking to follow up his Heat and Final double last time out here, whilst a couple of the super quick lower graders from the previous meeting like Luke Johnson (194) and Ian England (398) would be in the dizzy heights of the star grade. As it turned out yellow was the primary colour, as each of the five races were won by drivers from the yellow grade. 24 cars competed in a two thirds format. Paul Moss (979) won Heat and Final. Luke Beeson (287) scored a brace of victories in his Heat and the GN, with Josh Weare (736), in his first appearance in the ex-Luke Wrench (560) car winning the remaining Heat. Results: Heat 1: 979, 24, 976, 667, 27, 315, 581, 935, 895 and 438. Heat 2: 736, 992, 287, 581, 979, 184, 828, 27 and 325. Heat 3: 287, 992, 315, 115, 667, 184, 935, 976, 460 and 438. Final: 979, 287, 581, 115, 315, 24, 184, 667, 935 and 460. GN: 287, 24, 935, 581, 184, 27, 762 and 194. Taunton – Monday 26th July 2021 After a stand-alone Monday night fixture at the start of the month this meeting marked a run of five consecutive Monday evening events. Whilst some of the West Country drivers found it challenging to attend a Monday evening session a decent amount of long distance travellers boosted the numbers. Jamie Jones (915) from the Potteries, and the north-west pair of Phil Mann (53) and Aaron Vaight (184) would all be clocking up the motorway miles. Jones had been a regular visitor since making his debut in 2020, whilst Mann has regularly headed to the south-west throughout his career. As for Vaight his attendance record with Autospeed has been phenomenal. However, the furthest travelled for this meeting was Ulverston’s Josh Vickers (446). In addition to the rise of Ian England (398), and Luke Johnson (194) to the star grade there were three new 2021 Superstars in attendance. Kieren Bradford (27), Jamie Avery (126) and Tommy Farrell (667). Luke Trewin (529) debuted a brand new WRC Unfortunately it was christened after just a few laps in practice with a hard hit to the fence Pre-meeting proceedings commenced with appreciation and applause for two recently departed stars of years past, 1985 British Champion Nick Lawrence (ex-561) and George Beckham (ex-621), who finished third in the 1986 World Final. The 30 car entry raced to a full format with 8 through to the Final. Heat 1: Led by Lauren Stack (928) until five to go when the speedy duo of Steven Gilbert (542) and Ben Borthwick (418) moved to the head of the field. Borthwick kept close to Gilbert through the race but not close enough for a last-bender. Result: 542, 418, 127, 828, 895, 53, 988 and 232. Heat 2: The early leader was Richard Andrews (605) who was chased down by Ryan Sheahan (325) and Justin Fisher (315). These two in turn were hunted down by Paul Rice (850) who passed both for the victory with deft use of the front bumper. Result: 850, 315, 325, 315, 184, 605, 903 and 194. Consolation: All three superstars were present in this one after suffering DNQ’s in their respective Heats. Farrell had received a black cross for starting out of position, Bradford had crashed out with Mike Rice (438), and Jon Palmer (24) had retired with mechanical trouble. Stack built up a big lead which came to nothing when caution flags flew for Luke Trewin (529) who had crashed heavily in the pit bend. Luke was not having much luck in his new WRC. Lauren fell towards the back when the green came out but still qualified for her first Final. Palmer and Bradford had an easy run into the top two places. Result: 24, 27, 398, 438, 667, 928, 320, 446, 948 and 207. Final: The 26 car race saw a race stoppage almost immediately. Mike Rice (438) crashed hard into the turn four wall practically roof first after riding over the Matt Hatch (320) car. Stack led the restart away as five cars piled up into turn three resulting in Fisher (315) and Gilbert’s race being brought to a premature end. Charlie Lobb (988) then took over the lead spot until seven to go when Palmer shifted him wide entering the pit bend and setting sail for the win. Lobb suffered diff problems and he and third placed Charlie Fisher (35) ended up being shuffled back in the closing stages as the other stars - headed by Borthwick and Matt Stoneman (127) put the pressure on. With Stoneman secure in second, Borthwick shoved third-placed Sheahan wide on the last bend, which let Bradford come through both for third. Speaking to commentator Alan McLachlan (the Cowdie man on the mic, who travels down from Scotland for the Autospeed meetings) after the race Palmer said that passing all the red tops in one move early on was key to the win, adding: “Trying to catch little Charlie Lobb, that was the hard work!” Result: 24, 127, 27, 418, 35, 828, 325, 667, 184 and 605. GN: Andrews led until past halfway before Stoneman came through for the victory. Palmer showed plenty of speed on his way to sixth from the lap handicap without the help of a stoppage. Result: 127, 35, 903, 890, 605, 24, 315, 27, 184 and 667. A few pics in the gallery for the above three meetings Let’s now head back to last week’s abandoned site near to Matlock where we’ll leave the factory site and take on the undergrowth to get to Matlock Riverside station via the overgrown works branch. Through the undergrowth to the station. This is the point where the line branched off to the works. An original British Rail cabin, formerly located at Luffenham junction. The restored cabin is mounted on a non-typical stone-block base with an internal staircase to protect the box from vandalism, required due to its isolated location. The 19-lever frame was recovered from Glendon North Junction near Kettering. Mechanical interlocking allows the signals exiting and entering the loop via the Darley Dale end to be cleared in opposing directions when the cabin is switched out via the King locking lever. Continues below:

-

Hi there folks, We start this week with a summary of three July F2 meetings, we then return to the Permanite site near Matlock to find ourselves on the ‘rails’, before finishing up at the highest point on the A57 Snake Pass road to go and find the site of a 1944 air crash. Skegness – Thurs 8th July 2021 After a year lost to Covid the UK Speedweekend got underway with the traditional Thursday night warm up event. 65 F2’s were in the pits to race before a huge crowd. Ted Holland, the 2019 Irish Champ Bumped into Les Mitchell (ex-238), the man who won three consecutive Finals at Brafield in 1971. Heat 1: Long distance traveller Mike Philip (195), from Forres on the Moray coast, made the 8hrs 30 mins journey worthwhile with a fine second place finish. He had led the way for the majority of the race until being overhauled by Jordon Thackra (324) at the end. Result: 324, 195, 419, 226, NI998, 915, 127, 359, 629, 581, 844, 5, 674 and 854. Top 14 to the Final. Heat 2: 31 cars on track for this one. Brad McKinstry (NI747) powered to a convincing win with a classic last bend hit on Dave Polley (38). Result: NI747, 38, 78, 560, 184, 606, 315, 190, 482, 210, 512, 780, 236 and 564. Consolation: Only the top 8 finishers from this one to qualify for the Final. It was a tall order in a field of 34 cars including 12 Star and Superstar drivers. Jessica Smith (390) led until 2 to go when a race stoppage allowed the pack to close up. Jonathan Hadfield (142) went on to take another win in his new car. Result: 142, 968, 647, 667, 24, 584, 595, 890, 27 and 16. Final: This was another action-packed race which saw Micky Brennan (968) with a dominant win. His form since returning has been outstanding. He led Graham Fegan (NI998) and Luke Wrench (560) over the line. Result: 968, N1998, 560, 647, 127, 24, 210, 226, 629 and 38. GN: The last race of the night went to the 560 car as he headed a WRC 1-2 with Tristan Claydon (210) following him home. Result: 560, 210, 226, 629, 780, 78, 854, 419, 184 and 976. The Saloons were a big part of the UK Championship weekend, with 62 cars present for this Thurs night meeting. Heat 1: The opener began with a rollover for Rowan Venni (370) who was racing his brother’s car for the weekend. Sam Parrin (250), Dom Davies (261) and Bradley Fox (162) were up front early on. West Country duo Ian Govier (28) and Warren Darby (677) challenged for the lead with the 677 car taking the win. Top 3 result: 677, 618 and 525. Heat 2: Jordan Cassie (697) running from the front had a good battle with Michael Allard (349). Allard’s cause was helped by a caution flag for Steve Honeyman (607) after a massive hit from Graeme Shevill (661). Allard soon took the lead on the restart with a tussle for 3rd between multiple drivers with Irishman Kieran McIvor (811) surviving a ride around the fence for the place. Result: 349, 697 and 711. The 607 car after a huge hit from 661 Steve on with the repair Consolation: An air filter fire in the Venni car brings out an early caution. Fox leads from Colin Savage (14) and Tommy Parrin (350) in his new car. The end of the race saw the sparks fly when Shevill went in with a last bend attack on Andrew Mathieson (124) for the win. Result: 661, 124 and 350. Final: The Final was run in tribute to former Skegness marshal/starter Dave Garner. It was obvious from the start that Rob Speak (318) was determined to get the trophy. Austen Freestone (341) was soon in front with Darby the first blue, along with Speak the first red to make their moves. Freestone got a lucky break through the backmarkers with Darby going through as well. A caution closed the field up though which saw Speaky make his move into the lead. However, Freestone remained close in behind and attempted a last bend hit just missing the 318 back end. Darby nipped through for second. A great race with a fine drive by the promoter. Dave’s son, Jason the Skegness starter presented Rob with the trophy. Result: 318, 677 and 341. GN: Davies led this one but couldn’t hold back Allard who was on a mission winning the race from Barry Russell (600). Result: 349, 600 and 261. Bristol - Sunday 18th July 2021: An aerial view of the quarry close to the track This little acre of the Mendips was turned a shade of pink as the meeting was raising funds for Cancer Research. It was also a day to remember one time Mendip official Lesley Maidment as the F2’s were racing in the 10th running of the Pink Ribbon Trophy. Nathan Maidment (935) borrowed the John Brereton (948) car for the meeting Continues below:

-

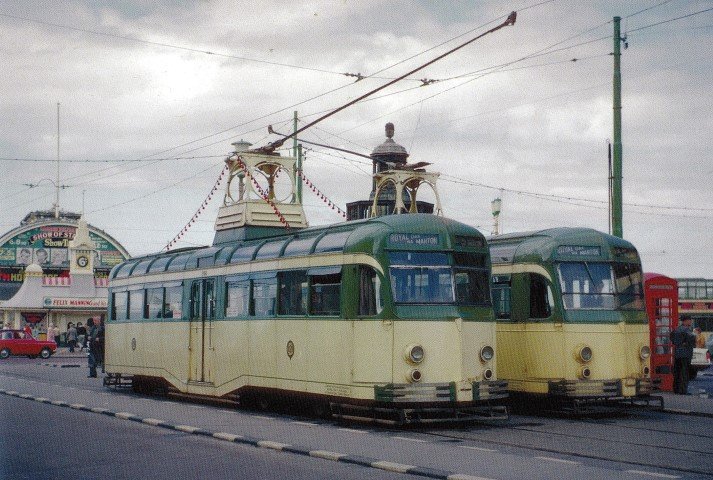

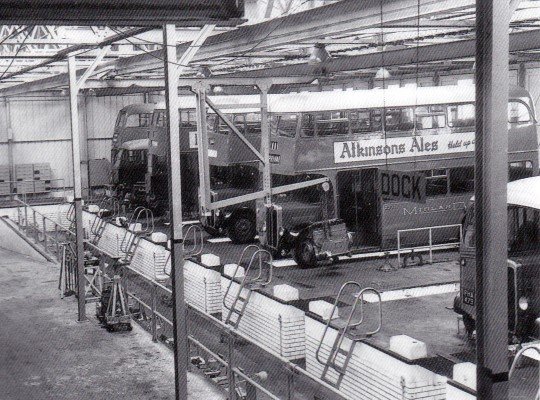

Continued from above: The latest pic in Trams in Trouble: A derailment for Brush Railcoach 637 at Central Pier on Sunday 21st October 1984. Sand on the line was the culprit. and in Miscellaneous: Hebble Motor Services, Halifax specified Bellhouse Hartwell ‘Landmaster’ bodies for four of their Royal Tiger PSU1/16 coaches in 1954. Their imaginative design was not unattractive but their 'Bug Eyed' nickname was predictable. One of several Hippo 20.H heavy recovery units commissioned by Leyland in the mid-1950’s for Service Depots, this one having a Lancashire trade plate from Chorley. The tanker on tow appears to have been on fire. Is this a Beaver or a different make altogether? The headboard has the name Meirion. Next time: F2 action from Skegness, Bristol (The Pink Ribbon Trophy) and Taunton. As mentioned above, the closed railway. We'll have a look at the remains of a ‘Flying Coffin’ on a wild and largely inhospitable gritstone moor.

-

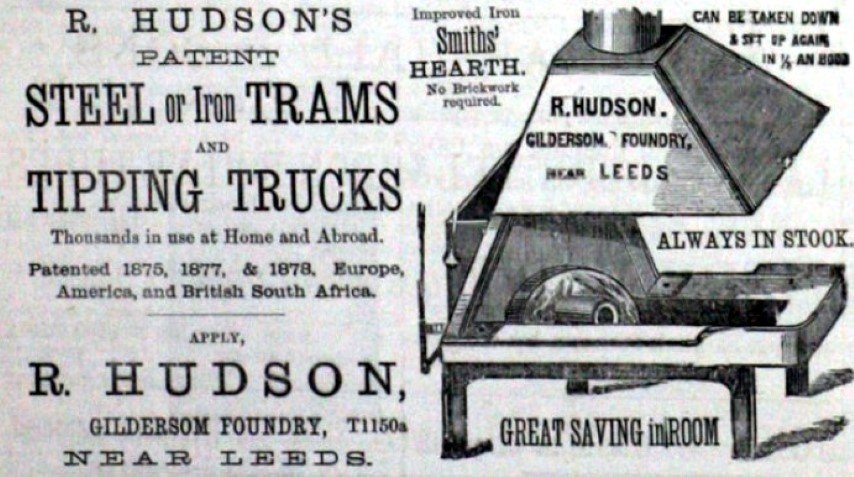

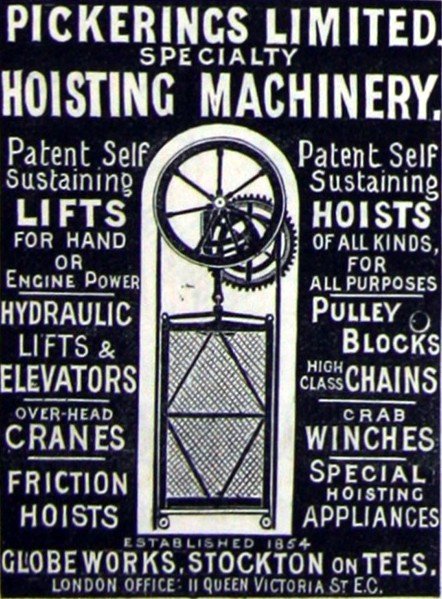

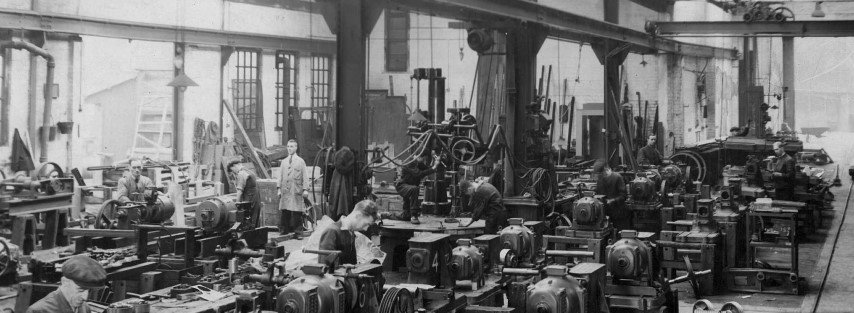

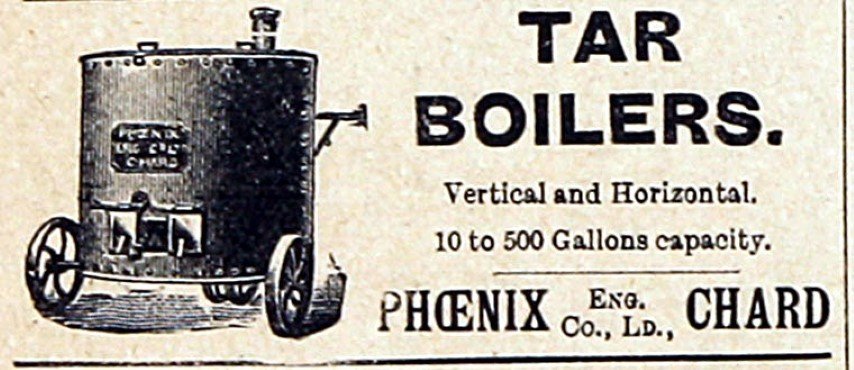

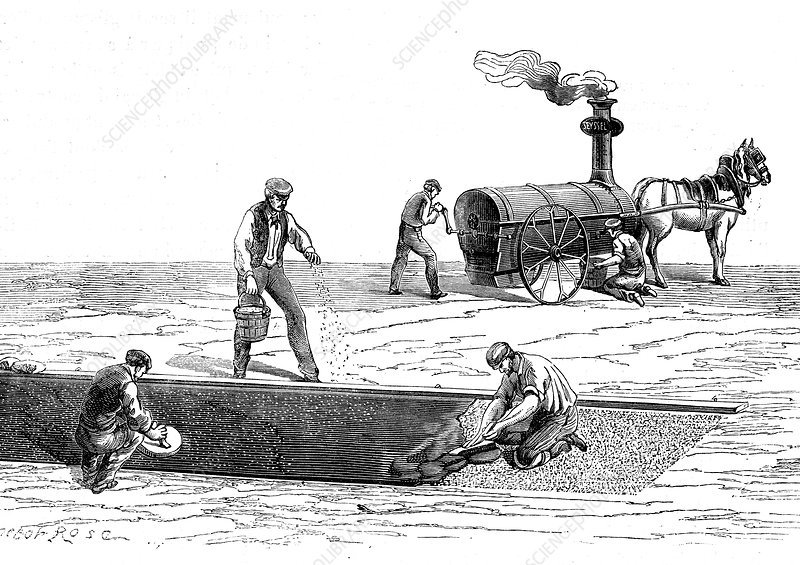

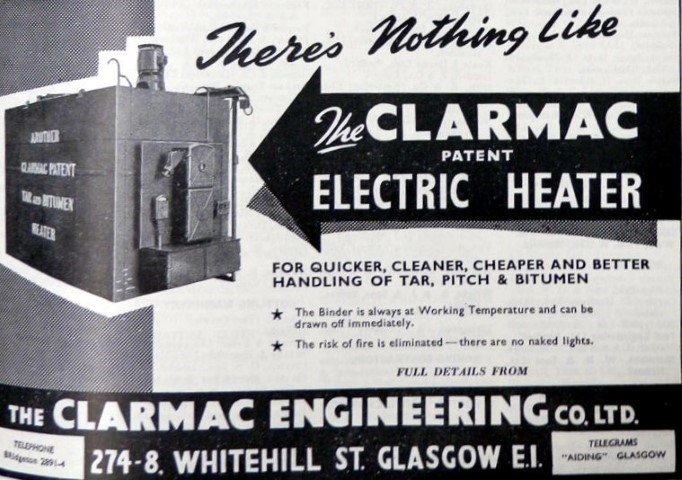

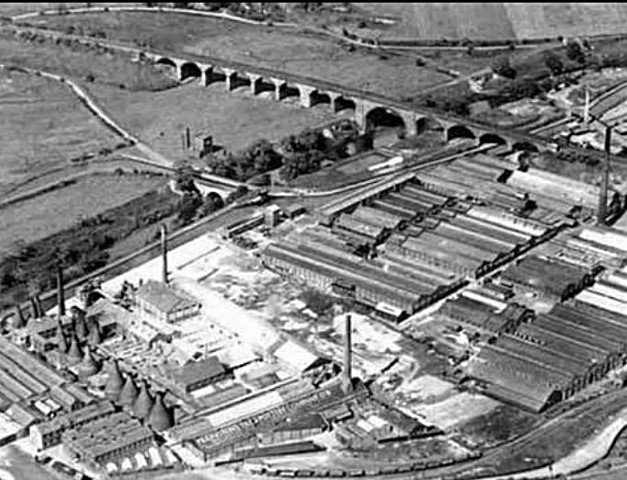

Continued from above: A lot of the rail equipment was supplied by Robert Hudson’s Gildersome Foundry at Leeds. (It was spelt without the 'E' on the end in their first advertisements for some reason. The company was established in 1865, with their works, the ‘Gildersome Foundry’ situated at Gildersome, nr Morley, Leeds. Their head offices were close to the Hunslet and Holbeck area where many of the engineering firms supplying factory machinery and railway equipment were situated. The Hudson's were a wealthy family with interests in the mining industry, and supplying this industry would provide much of the work for Robert Hudson. They specialised in providing light railway equipment such as prefabricated narrow track sections and various designs of wagon. The company would also supply locomotives but these were entirely sub-contracted to other companies that specialised in locomotive production. As well as supplying complete railway systems they supplied rope haulage systems. At its peak the Gildersome Works occupied a 38 acre site with pattern making shops, a foundry with two Bessemer furnaces, machine shops, erecting shops and a drawing office. The sort of narrow gauge system they could supply was well employed in their own works. An extensive 2ft gauge system was used for moving materials around the site, the wagons being pushed along by the workers, or a road tractor for heavier loads. The works were situated alongside the Great Northern railway line, where sidings were provided for receiving raw materials and dispatching completed products. One of the most successful Hudson Products was the small tipper skip wagons made from their early days. In 1875 Hudson patented the ‘rolling triple centre pivot’ this provided three points at which the skip wagon could sit securely, in the centre for movement, and tipped over 90 degrees to either side for unloading. Many of these were made and can still be found all over the world. A key to the success of Hudson’s wagons were their roller bearings which meant they required minimal force to move them. Wagons could be pushed around by hand, or very long trains could be pulled by a small locomotive or animal. Sadly, the company ceased trading in 1984 owing to cheaper, and therefore inferior products from abroad. Back at Permanite the wagons could be moved from upper to lower levels in a lift complete with rail lines. Looking down the track to the lift The lifts were manufactured by Pickerings of Stockton-on-Tees who are still in business today. A company that has weathered the storm which has decimated British industry over the years. Pickerings Lifts is one of the oldest engineering firms in the United Kingdom, with an unbroken history of family ownership and management, now in its fifth generation. They are the UK’s leading lift specialist company, starting from humble beginnings over 160 years ago… Jonathan Pickerings first set up as a maker of pulleys, blocks and chains during the Crimean War. Keen to expand, Jonathan soon turned his hand to developing self-sustaining hoisting equipment. He showcased his revolutionary pulley-block and hoisting equipment at the Centennial International Exhibition, the first official World's Fair, in Philadelphia, USA, in 1876 (also on show were Alexander Graham Bell's telephone, and the Remington typewriter). Success led to exhibitions in Germany and Holland, achieving medals for excellence and design quality. In 1888 the first commercial electric lift was designed, manufactured and installed by Pickerings Lifts for the Middlesbrough Co-Operative Society. Pickerings Lifts also invented the self-sustaining hand lift and service lift, developing belt-power, and hydraulic lifts. In 1896, they reached another industry milestone with the invention of the first fully automatic push-button lift, a considerable feat of engineering and innovation for the time. The company carried out work of national importance during both World Wars, including the manufacture of balloon winches and field power/traction units. Later came the trench mortars and components for Bailey Bridges and floating pontoon bridges during WWII. They also installed the ammunition lifts for the long-range cross-channel guns near Dover. The Gildersome Works In 1932, Pickerings Lifts was a Founding Member of the Lift & Escalator Industry Association (LEIA), which is still going strong today. In 2008, they incorporated escalators into their portfolio becoming a comprehensive service provider for their customer’s requirements. In 2010 they were selected by US Based 4Front Engineered Solutions to be the UK’s sole distributor, bringing a wider range of products such as sectional doors, loading platforms, dock levellers, and vehicle restraints to their portfolio. Today, Pickerings Lifts is the UK’s Leading Lift Specialist, offering customers their expertise and experience to maintain, repair and modernise any lift, escalator, mobility and loading bay equipment. Moving on we come to the blender tanks. They still have a very sticky residue leaking from the discharge points. The smell of tar lingers on. These tanks were manufactured by another surviving success story – Phoenix Engineering of Chard, Somerset. The First Phoenix: The story of The Phoenix Engineering Co. Ltd. starts back in 1839, when the Smith Brothers’ Phoenix Iron Foundry started trading. 45 years later Edward Rusk, a London financier, acquired the freehold to the foundry and in November 1891 he set up the Phoenix Engineering Company Limited in order to buy the Phoenix Iron Foundry. Rusk was the majority shareholder and the rest of the capital was owned by some London-based engineers, Roger Bolger Pownall, Charles Harris, and Thomas John Jennings, who was the company secretary. Phoenix Engineering Company Limited continued to manufacture the same product lines as the Smith Brothers had, as well as pumps for the Pulsometer Engineering Company. Thomas Jennings had worked for Pulsometer and the pumps he now produced were to be sold under the Pulsometer brand name. A New Phoenix Rises: Between 1891 and 1904 Phoenix made an annual profit only twice so in 1905 it was decided that a radical re-organisation was necessary. Thus a new company was incorporated by the directors to buy the Phoenix Engineering Company Limited, and to acquire the freehold of the Phoenix Iron Foundry from the estate of Edward Rusk, who had died in the February of that year. The shareholders in the old company were issued shares in new company, The Phoenix Engineering Co. Ltd., on a one-to-one basis, thus giving Edward Rusk’s executors control. In 1906 the new Phoenix made an annual profit of £269/8/8 on a turnover of £4538/16/8 and product lines were expanded to include bitumen heaters and sprayers sold under the Rapid trade mark. Then, in 1909, Phoenix signed an agreement with Llewellin and James of Bristol, one of their biggest competitors at the time, to become the sole supplier of all their tar boilers and the two companies agreed to sell their boilers at the same price. Early road builders Expansion and Exports: During WWI Phoenix increased their manufacturing operations to include agricultural machinery and after the war found a good market for bitumen equipment and pumps in the British Empire. This was the beginning of their strong export figures. Along with countless other companies, Phoenix was badly hit during the recession, as public spending on roads was drastically cut, but with the advent of WWII there was an increased demand for their products. In fact, demand was so great that the War Department ‘gave’ them a subcontractor in Glasgow for the production of bitumen boilers. Phoenix then streamlined their product lines, mainly producing bitumen equipment, pumps, and temporarily, field kitchens. Ground Breaking Design: In the early 60’s the original foundry was closed and the manufacture of pumps ceased. John Pownall developed the self-propelled chipping spreader, and spreaders based on his design, plus bitumen heaters and sprayers which now accounted for the vast majority of the company’s sales. During the 70’s Phoenix concentrating on increasing their sales overseas and in 1977, at the height of the oil boom in the Middle East and Africa, won the Queen’s Award to Industry in recognition of their achievements in the export markets. Phoenix Continues to Flourish: In 1997 they again won the Queen’s Award to Industry for Export Achievements, and exports over recent years averaged at 65% of total sales. They have exported Chard-built equipment to many countries, including Vietnam, Laos, the West Indies, Nepal, Mongolia, Japan, as well as Western Europe, Africa, the Middle East and the Far East. Phoenix continues to go from strength to strength as it nears its 122nd birthday and is still run by descendants of the original founding families. The bitumen mix is heated up using Clarmac Heaters Back in 2002 this article appeared in the Scottish newspaper, the Herald: Hard work and perseverance pull Clarmac back from brink. Engineering firm saved from receivers by buy-out: In a sprawling industrial yard in the east end of Glasgow, an unusually loyal band of engineers laboured through the winter without pay, giving up their own time in an act of faith that a new owner could rescue their old firm from the clutches of the receiver. The team, who had all been made redundant from Clarmac Engineering when the parent firm called in the receivers, pinned their hopes on three men with a vision of buying back the business and relaunching it as an independent company. Allan Kincaid led the trio of directors, which also included Malcolm Stewart and Eric Welsh, in a bid to buy the 74-year-old business from the receiver, which was called in last November. Last weekend the Clarmac team lifted three massive bitumen storage tanks onto lorries for delivery to clients in the quarrying industry, marking the first big order for the reborn business. The journey from receivership to start-up was fraught with difficulties, says Kincaid. He attributed the successful start-up to perseverance, the loyal support of the old workforce, financial backing from the Royal Bank, and sound advice from Business Ventures (a group within Scottish Enterprise Glasgow dedicated to helping start-ups). Back in November, Kincaid and his fellow directors were so convinced the business had a future they pledged their redundancy money to back a management buy-out, but that would only provide a percentage of the required capital and a bank loan was vital. Kincaid was negotiating to move the business from Dennistoun to 16,000 sq ft premises in Carntyne before the receivers moved in, and he decided to continue with the plan. He had enlisted the help of Scottish Enterprise Glasgow to find the new site and was encouraged by them to formulate a buy-out plan. ''Once we'd decided to buy the business we were introduced to Andrew Brocklehurst from Business Ventures and he was a tremendous help in steering us through the preparation of the business plan, and over the financial and legal hurdles. I think it's fair to say that without the assistance we got from Andrew we would not have a business today,'' Kincaid said. The Royal Bank liked the buy-out idea but issued an ultimatum to Kincaid: deliver proof of orders within 48 hours or the funding deal was off. Kincaid and his team called customers all over the UK, from quarries to oil companies, who are the main customers for the thermally-insulated steel tanks used to store and transport bitumen at 200 degrees Celsius. ''We got 30 or 40 positive responses and submitted the first 20 to Paul McGuinness at the Royal Bank and the underwriters decided to back the project'', Kincaid said. He also obtained letters from suppliers, pledging their willingness to deal with Clarmac under new ownership, and in early January Kincaid's team paid for the assets of the company. No-one was more relieved than the seven redundant engineers, and a PA whose hopes of future employment were riding on Kincaid's plan. ''There were times when we could have walked away because there were just so many obstacles, but Andrew Brocklehurst used to tell us we had to jump a different fence each day,'' he said. Kincaid expects turnover to reach £1.2m in the first year and he hopes in future to invest in new machinery to allow Clarmac to diversify into other markets which require bulk storage, such as the food industry. He has already begun collaborating with Paisley University on new product development. However,i can't find much info on the company today so can only assume it has ceased trading. The tank heating controls are supplied by Sunvic: Sunvic is proud of its British heritage. For over 70 years they have manufactured central heating products from their UK base in Lanarkshire, Scotland. Sunvic Controls Limited have continued to expand its range of products. Their location and structure allows them to service clients across the UK and the rest of the world. Sunvic's market leading products are developed by a team of highly qualified engineers experienced in mechanical, electrical and electronic design and use leading edge technology to meet progressive new product requirements. That's some pedigree. Coming to the far side of the site we find a loading bay. In the roof is a halogen heater which unbelievably still works! Close to here is a gas oil tank with another two Coloquix works applied to the sides. This area was used to store the finished product before dispatch The same scene in its heyday. Note the Foden tanker. That is about it for the main parts of interest here. There are other buildings and store rooms on the site but most are now empty. If you do plan a look around be aware there are some big holes and tanks to fall into. The tall building has plenty of opportunities to lose your footing and plummet to ground level. Plenty of pics in the gallery. As a bonus it’s possible to bushwhack through the undergrowth and get onto a closed railway line. We’ll have a look at that next time. Continues below:

-

Continued from above: On the very upper floor the hoppers are open-topped. If you slipped into one of these there’s no getting out! They go a long way down. A screw conveyor left behind There are also some big open drops down the stairwell which would be a game over moment. There is a walkway outside to some big external hoppers which is also unfenced. There is a lot of graffiti throughout the site, including some fine works of art by Coloquix A number of abandoned places in Derbyshire feature paintings by the Sheffield based artist. Back at ground level a passage connects to the building containing the unprocessed bitumen vats. It was here that I heard the sound of an approaching gang. It crossed my mind that this is where the camera gets nicked. Sure enough they soon spotted me and strolled over. “Who are you, where are you from, and what are you doing?” the designated head of the group asked. I said,” Taking pictures of the graffiti” It was a lucky answer as from that moment their hostility evaporated. One of the lads was a graffiti artist and had a holdall with him which contained spray paint and charcoal pencils for creating fresh art work. They regularly added to the stuff already there so were very eager to explain the meaning of most of it. They turned out to be a great bunch of lads, and to top it off did a personalised one for me. It just goes to show you can’t judge people on first impressions. No doubt if i’d told them to do one i’d have probably been chucked in the lime hopper though. Throughout the buildings there are rails remaining from the narrow gauge internal network used to move the wagon loads of limestone powder, silica and sand around. There are even points and small turntables. Continues below:

-

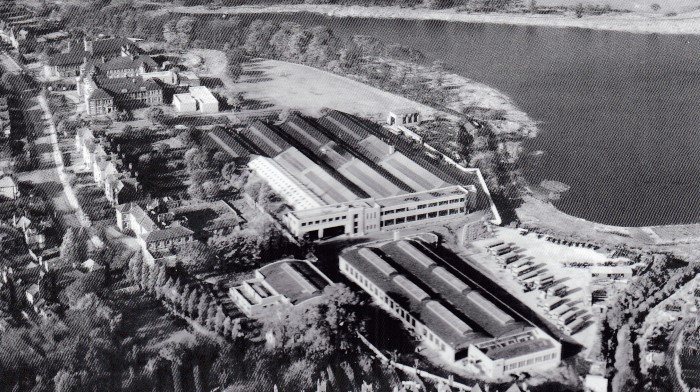

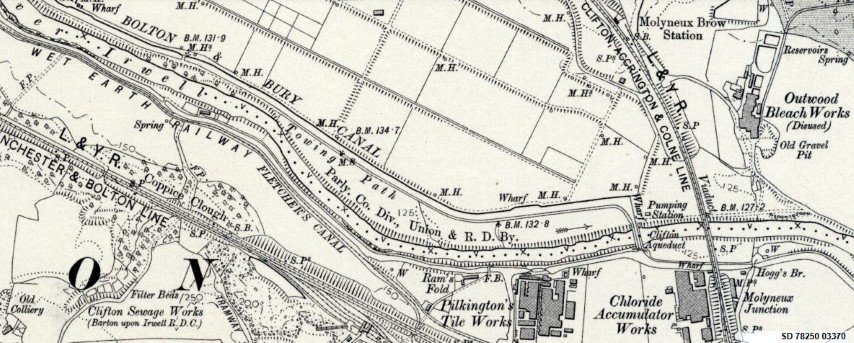

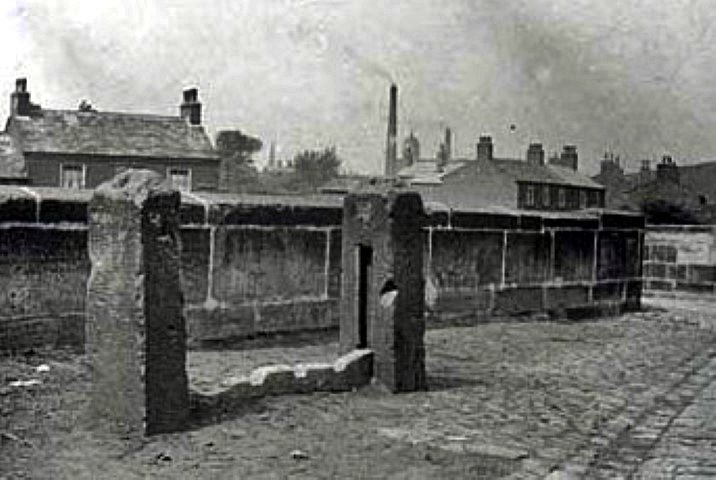

Continued from above: The aerial view below shows the location of the works arrowed at top left, with the quarry bottom right. The railway network connected with the two sites is shown in yellow. A spur was taken from the Millers Dale to Ambergate line which runs parallel to the A6. Only a tantalising glimpse of sleepers amongst the undergrowth is all that remains of the railway. Getting into the site was easy, no high fences to climb or security providing you don’t try it from the Sainsbury’s side of the site as there are operational cameras. It’s a great place to spend a few hours with loads to see. However, being close to Matlock it does attract its share of youths, and characters under the influence of various substances. We’ll meet some later! Let’s get inside and see what we can find. Pics in the gallery follow this walk through in order. The first building we come across is between the old quarry and the main site and was used as a mixing shed. Looking like it should be in the 'Texas Chainsaw Massacre' The inside view As we pass through the entrance gates an old weigh bridge is still in situ. A number of high floodlights are still standing here. Moving further in to the site the main buildings come into view. As it is now and from an earlier time Passing these first two buildings we come to the ‘big shed’ where the moulds were allowed to cool. The roof fans were eerily still circulating. Next to this is a multi-storey red brick building which contains the hoppers for the limestone. There’s lots of powdered limestone still about in here. The Middle Peak Quarry was the main supplier of this. Looking up to the mechanism for the tall hoppers Continues below:

-

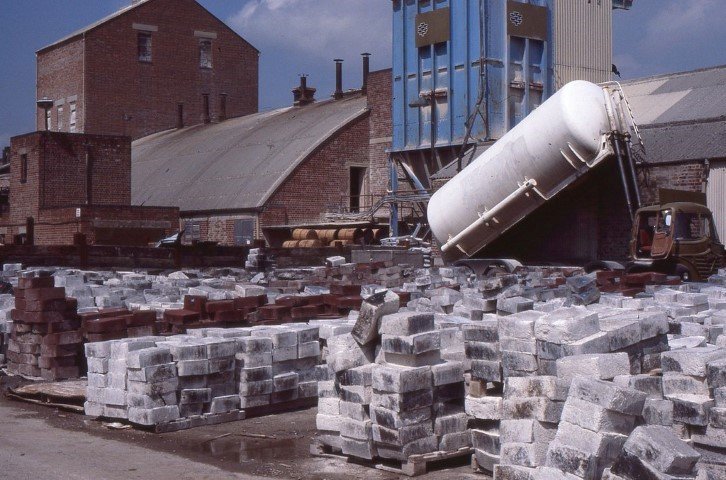

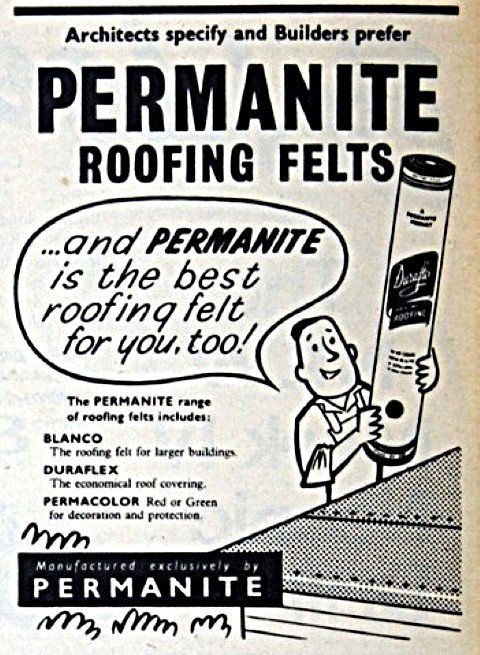

Continued from above: Cowdenbeath - Sunday 27th June 2021: Just before the railway bridge in Cowdenbeath town centre a local artist has painted her latest fantastic mural on a gable end. I stopped for a chat and she told me that the best thing about it is the fact that nobody has added graffiti to them as they are respected symbols of the town. This was the third mural she had done following on from ‘Miner Boy’ and ‘Shopkeeper’s Daughter’ Miner Boy Shopkeeper's Daughter Detail h/with from the local paper: The finishing touches have been made and the paint is dry on the latest giant public artwork to be unveiled in Cowdenbeath. Respected Fife artist, Kerry Wilson, has completed her third mural in the town, which now takes up the entire gable end of a building in High Street. Shoppers have stopped to stare while traffic has been brought to a standstill as people admire the 30-foot image, commissioned by Cowdenbeath Community Council. Details of what the picture would be was a closely guarded secret as Kerry set about creating her latest masterpiece. And with the scaffolding finally down, locals have been stopping to wonder at the latest addition to the burgeoning public art collection Cowdenbeath is now being recognised for. This time, Kerry has created stunning image of a young boy laying down playing with a ministox car and breakdown vehicle of the type seen at the Racewall in the town. She admitted it has been her most challenging work to date. "By deciding to have the image fading out of focus the further back it goes I’ve certainly not made it easy for myself,” Kerry said. “But i push myself and never shy away from a challenge.” Despite her talent, it was far from easy for the Kirkcaldy-based artist, who has faced a number of delays. As well as having to dodge heavy rainstorms, work was also halted after the discovery of a bee hive within the chimney stack. “The rain meant I had to chalk out the design on the side of the building after it was washed off,” Kerry said. “And the bees couldn’t be moved as they were protected as they had been there for many years.” The council had been trying hard for five years to attract more people into the town centre and increase footfall and the artwork was a focal point of that. “And it’s just great to know that people in the town are as pleased and proud of the art as we are.” a spokesperson said. Local councillor Darren Watt said he was “amazed” by the result after watching as the artwork come to life over the weeks. He added: “Like other local residents, I am delighted to see the latest mural unveiled in the town centre. This is an exceptional addition and praise must once again go to the artist, Kerry Wilson. It’s a real asset to have incredible artwork throughout our town and High Street." “Hopefully this helps give visitors another reason to stop by and experience what Cowdenbeath has to offer.” A unique occasion awaited at the Racewall where both the F2, and Saloon Scottish Championships were being held on the same day. It was the 40th running of the Championship for the F2’s, and very much part of the history of GMP Scotland since that very first season back in 1981. Over the years the race had been won by many of the greats in the sport including Bill Batten, George MacMillan, Garry Hooper, Ali King and Rob Speak. It was a sunny and warm afternoon and the fans had flocked to this meeting. There were lots of cars in the pits with the majority of long-distance travellers stopping off on their way back home from Crimond. Martin Ford (4) the previous evening’s winner was absent as were a few of the Crimond drivers although Ryan Farquhar (419), Colin Stewart (191) and Jason McDonald (387) had made their way down. A full format for the F2’s once again. Heat 1: An exciting finish to this race. Gordon Moodie (7) had got ahead of Paul Reid (17) entering the pit bend on the last lap but Reid got the better drive out and went through to win. Result: 17, 7, 647, 674, 78, 86, 280, 387, 915 and 182. Heat 2: Craig Wallace (16) claimed the victory, and as in the previous race it was on the last lap that he got the lead. Result: 16, 652, 629, 144, 618, 236, 512, 402, 419 and 391. Consolation: After an early race stoppage Dean McGill (263) led until three to go when Liam Rennie (3) swept past for the win. Result: 3, 263, 419, 391, 251, 182, 237, 881 and 444. Final: The cars lined up for the Scottish in a drawn within grades grid. Jack White (182) led the field away but shortly after the start Jess Ward (86) was cannoned around the top bend. On the pit bend Peter Watt (280) and McGill tangled with the 263 pinned against the wall. The yellows flags flew. McGill’s bumper needed removing before they could disentangle the cars. At the restart Ward was hit entering the pit bend and ended up losing a wheel against the fence. Caution period number two. White led the single file train away as Moodie pulled off with a flat. Within a few laps Stephen Forster (652) took the lead. At halfway Rennie was slowly closing in second, with Chris Burgoyne (647) a couple of car lengths further back. With six laps to go 647 moved into second and began making rapid inroads to the leader passing him for the lead and the win with two left to run. Rennie pipped Forster over the line for second. Result: 647, 3, 652, 674, 16, 387, 78, 618, 236 and 144. GN: Paul Reid took the win from Moodie and Rennie. Result: 17, 7, 3, 674, 647, 629, 402, 144, 16 and 618. Saloons: The 25 cars were reduced by one after practice with the 640 car blowing an engine. An all-in format was employed with each driver racing twice. Heat 1: Logan Bruce (601) made a good start but within two laps the flags flew for a rolled Willie Mitchell (96) after he caught a marker tyre. Both Graeme Shevill (661) and Steve Honeyman (607) came to grief in a back straight jostling match. Just after half-distance Stuart Shevill Jnr (618) was leading when Eck Cunningham (45) was stopped on the entry to the home straight being collected by Cameron Milne (60). Within a couple of laps of the restart Kyle Irvine (85) sent 618 wide and swept past for the win. Shevill slowed and stopped. Top 3: 85, 73 and 684. Heat 2: An easier race for 618 this time as he took the win from James Letford (73) with a forceful move with three to go. Result: 618, 73 and 85. Final: Irvine and Letford occupied the front row, while behind were Ian McLaughlin (684) and Shevill Jnr. Irvine took the lead at the drop of the green as a considerable amount of bumper-work saw Holly Glen (8) left on the football pitch within a lap of the start. The race was halted to help Holly out of her car. Irvine made a good restart but had Barry Russell (600) making a robust bid to either take him out, or take the lead. As he did so it delayed defending double champion McLaughlin and Shevill moved in to second. Russell clipped the wall and retired. The front two cars extended their gap as the rest were exchanging positions. Just after halfway Honeyman switched to all-out attack mode on Graeme Shevill entering the turnstile bend which ended up with both parked up nose to nose on the pit bend run off. Shevill and Honeyman nose to nose With the laps winding down Irvine pulled away from 618 to take the victory. Result: 85, 618, 5, 684, 661, 670, 122, 229, 73 and 96. Pics in the gallery Okay folks, we head for Derbyshire now to have a look around the abandoned Permanite works. Opening in the 1960’s Permanite Asphalt, located just outside Matlock, was originally part of the larger Cawdor Quarry complex. It was incorporated in 1989 and manufactured various asphalt products, mainly flooring blocks used to waterproof floors, as well as roofing sheets. The process involved the mixing of aggregate, bitumen, sand and limestone. The plant took powdered limestone from several of the local quarries and mixed it with hot bitumen emulsion that was brought down from the refineries of Ellesmere port, this being a bi-product of the fuel oil-refining process. It would all be mixed at 200 C for about 5 hours. The mixed tar and limestone solution was poured into metal moulds on the floor of the big shed and allowed to solidify. It was done by hand and was heavy and gruelling work at 25 kilos per full bucket. The work paid well, around three times more than the average wage at the time. The back-breaking process of manually separating and stacking the cooled blocks followed. During the late 80's part of the process was mechanised when Permanite spent a lot of money on a shiny new plant but this kept breaking down. The site was regulated by the local Derbyshire Dales District Council on the condition that the heating of tar or bitumen was regulated under section 6.3 of the Environmental Permitting Regulations. In 2009, Permanite Asphalt relocated 7 miles away to Grangemill, becoming known as Ruberoid, which is part of the IKO Group. The company was dissolved in September 2016. It's likely this site is not going to last much longer, the locals have pretty much lost the war against housing developers and apart from a small victory over some adjacent fields it's all earmarked for houses. In 2018, developers Groveholt Ltd submitted plans for 586 houses in total for the ‘Matlock Spa’ development - with 468 of the homes to be built on the brownfield sites of Cawdor quarry, and the former Permanite works. As of 2021, these plans had yet to get off the ground, and the site remains derelict. Continues below:

-

Hi there folks, We start with a racing trip to Scotland, and then onto Derbyshire for some industrial abandonment. We finish off with the latest pics in the ‘Trams in Trouble’, and ‘Miscellaneous’ series. Lochgelly – Friday 25th June 2021: Considerable investment has been made to the facilities The Superstox were in action, and a welcome visiting driver was Gary Chisholm in what was his first outing at the track. The Superstox had provided some competitive racing in 2021 already, with a number of lower graded drivers stepping up and stealing the plaudits from those further back. Bryan Forrest had been in super form though, and scooped a hat-trick of race wins at the last outing just a couple of weeks previously. Dean Johnston seemed to be getting his new car up to pace, and put in his best performance of the season last time out - could he get more out of it on Friday night? The answer was a resounding ‘yes’. The Johnston (446) transporter Top 3’s: Heat 1: Bryan Forrest (309), Mark Brady (171) and Dean Johnston (446). Chissy was a non-starter owing to engine trouble. Heat 2: 446, Jack Turbitt (217) and Kenny McKenzie (453). Chissy in 9th. Final: Lee Livingston (55), 446 and 453. Chissy in 8th. Crimond - Saturday 26th June 2021: For those that live close to the raceway it was a case of, “Fit like a foo are ye dein”, or, "Hello and welcome", for everyone else to the F2 Challenge Trophy, and WCQR meeting. This was only the second ever Championship event for the class to be held at Brisca’s most northerly outpost. With intervention by Autospeed’s Crispen Rosevear, and the assistance of fellow Scottish F2 promoters GMP the track was able to swap its traditional Sunday race day to Saturday evening. Any long-distance travellers would be able to travel home on Sunday after the F2 Scottish Championship, and WCQR at Cowdie. Long-time retired racer Graham Kelly (721) had wished to return to racing in 2020 to celebrate Crimond’s 50th year but their season was postponed completely. He had been waiting patiently to make his official return and was ready to go. This was going to be the biggest ever field of F2’s to attend Crimond Raceway with 35 cars booked in. There were quite a few visitors, the furthest being Jamie Spence (903) who had travelled 600 miles from Basingstoke, followed by a trio of East Anglians - Henry King (78), Jess Ward (86) and Craig Driscoll (251). From the north of England came Martin Ford (4), Andy Ford (13), Jack White (182), Mark Taylor (444), Ben Lockwood (618) and Jamie Jones (915). Furthest-travelled Scot was Euan Millar (629) from Lockerbie. He still had a 4 hr run. There were a few last minute cancellations but a good turnout of 31 cars raced in a full format meeting. Practice saw Paul Reid (17) almost roll it after hitting a marker tyre, and Mike Philip’s (195) engine let go. Heat 1: Mark Taylor (444) made an early break but swiftly lost out to Scott Paterson (779) who held the lead for a number of laps before he was passed by Stevie Forster (652). The 652 car claimed the victory from Liam Rennie (3), and Gordon Moodie (7). Result: 652, 3, 7, 78, 854, 419, 915, 674, 86 and 444. Heat 2: Graham Kelly and Andy Ford both spun at the start and lost time. Colin Stewart (191) took the lead at the halfway point to win from Jack White (182), and a fast closing Craig Wallace (16). Result: 191, 182, 16, 387, 4, 629, 618, 251, 647 and 480. Consolation: Jamie Spence’s long journey north was rewarded by a fine first ever F2 victory in this one by a big gap back to Philip and Kelly. Result: 903, 195, 721, 236, 512, 17, 779, 13, 343 and 922. Final: The grid was drawn in grade order and saw White take an early lead. At the rear of the field Moodie and Robbie Dawson (854) started the latest instalment of their long-running feud. Jason Blacklock (512) was stuck at the pit bend bringing out the yellows. Dawson managed to disentangle his car from the tyre wall and lined up for the restart. Robbie attempts to break free as his sister Laura (F2 - 54) in the grey bobble hat to the right of his wing looks on As soon as the green flag dropped he clashed again with 7 who retired from the race. White was still leading ahead of Martin Ford with Jason McDonald (387) heading the red top chase. Ryan Farquhar (419) spun but carried on, then a four car pile-up in the town bend brought out the caution. Ford was the new leader at the restart and eased away from the field to a jubilant victory. Action followed behind with Chris Burgoyne (647) and Kelly losing ground with the 721 car sustaining rear end damage. Result: 4, 387, 16, 629, 3, 78, 480, 647, 619 and 419. GN: A dramatic collision between Philip and Garry Sime (480) ended up with the 195 going airborne over the 480 car whose wing got written off in the process. Wallace took the victory ahead of Stewart and Dawson. Result: 16, 191, 854, 629, 618, 419, 387, 236, 86 and 182. Pics in the gallery Continues below:

-

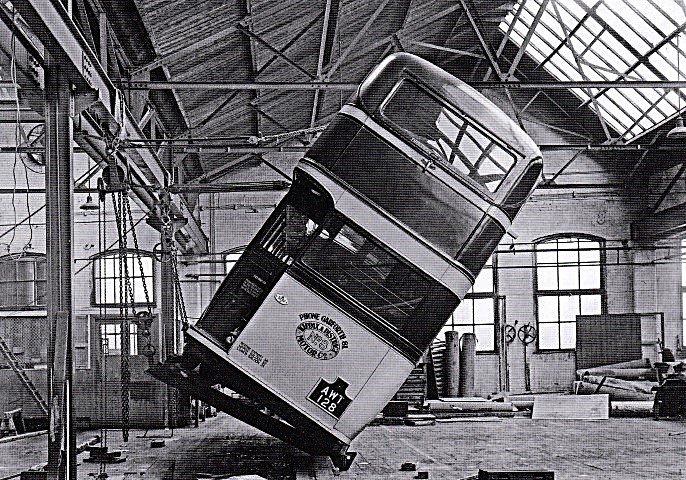

Continued from above: Finally, here’s the first in a series of Trams in Trouble pics: English Electric Series II Railcoach 612 at Alexander Road tram stop on Tuesday 20 June 1972. 612 was taken out of passenger service following the accident. In March 1973, the bodywork was scrapped down to the basic wooden frame. This was carried out either in Blundell Street tram depot or Rigby Road tram depot. The tram later became OMO car 8. (Pic credit to the Evening Gazette) Also the first pics in a new Miscellaneous series: What would normally be called a ‘tilt test’, Leyland Motors always used to describe as the ‘gravity test’. The piece of equipment used was frequently moved around the factory, but here we see it in the Body Shop of South Works, near to the Paint Shop. The method of carrying out the test looks quite simple and presumably the frame was safely anchored to the floor along the ‘hinge’. One wonders if they ever had any mishaps, potentially very expensive mistakes! At least, this body had a metal framework. It is one of the later ‘Vee-front’ all-metal Leyland Highbridge bodies. The bus was destined for Kippax & District Motor Co, Garforth, West Yorkshire. It was a Titan TD4 and was photographed on 3rd September 1935. The oval enamelled plate on the back is numbered 5230B, being the PSV licence number, the ‘B’ denoting the Yorkshire traffic area. A Leyland TB10 demonstrator trolley bus covered some 1,300 miles on test around Chesterfield. It was a three-axle double deck vehicle, with front and rear entrances, with a seating capacity of 63. Back next week with the Scottish reports, and industrial dereliction.

-

Continued from above: AEC Routemaster – CUV 213C (RM2213). New in May 1965 and remained in active service until 1994 when it was transferred to the reserve fleet at Hatfield. Left here in 1998 and was sold to KD Coach Hire of Dyserth, North Wales. Bought by her current owner in 2019 after being owned by preservationists in Scotland, Southampton and Peterborough. Alongside is Leyland National – JTU 588T (SNG588). New to Crosville in May 1979 and operated as part of the Wales & South Cambrian fleet. Sold to Glasgow Airport and converted to double door. Later, it was sold again as a training bus and then finally a café before rescue by a preservationist in Scotland. The Gardner sounded superb reverberating off the walls in Chester Former Alder Valley Leyland National – KPA 369P. Alder Valley was formed on 1st January 1972 when the National Bus Company (NBC) merged two subsidiaries, Aldershot and District (A&D,) and Thames Valley Traction (TVT) RFM 641 - 1953 Guy Arab IV, Massey 56-seat double deck originally Chester City Transport No 1. The RE looking magnificent at dusk A rear view of RM765 and BL88 and from the front. The soft glow of the Routemaster’s interior lights add to the atmosphere. Continues below:

-

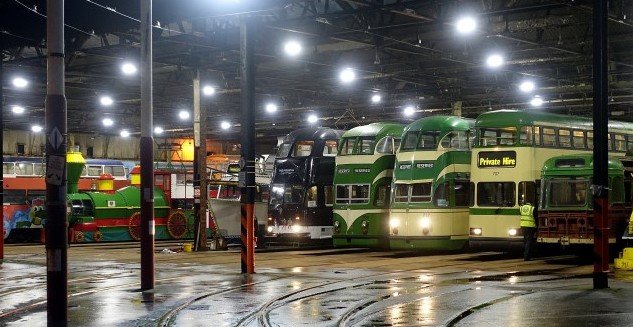

Continued from above: The third leg was a tour through the Illuminations, followed by a recreation of the final passenger journey of the traditional tramway on 6th November 2011, using modified Balloon 707 (which operated that final journey). The modified 707 707 pre-modification Technical Information: Built: 1933 - 35 as Balloon originally (rebuilt as millennium car 1998 - 2004) Builder: English Electric, Preston Capacity: 84 - 94 seated (varies per fleet member) Numbered: 707, 709, 718, 724 Trucks: EE equal wheel bogies, 4ft 9 inch wheelbase Motors: EE 305 HP 57 x 2 Controllers: EE Z6 Top Speed: approx 35 mph Braking: Westinghouse air wheel, rheostatic 8 notches, hand- wheel Current Collector: Pantograph Current Operation: part of B fleet, can be used on normal service if needed In 1993 Balloon 707 was withdrawn in need of a major overhaul. At first it was assumed that 707 would receive a similar style of overhaul to the other Balloons being overhauled around that time. After a couple of years in store awaiting its turn in the queue, work commenced on 707 and the tram returned to service in 1998. The refurbishment featured enlarged drivers cabs with flat fronted ends with rounded edges giving the tram the appearance of a double decked railcoach/twin-car, and high visibility headlights. The addition of the high visibility headlights allow clear visibility in the poorly lit northern section of the tramway at night, allowing the tram to be allocated to the evening Fleetwood services. Internally, the tram car has central heating and bus style seats featuring the traditional moquette. The car re-emerged repainted with the Millennium style green, cream and black livery. Initially the upper end corner windows were omitted, however these were retrofitted at a later date, giving improved all round view for the passengers. Opinions of the rebuilding of 707 were mixed at the time that the tram re-entered service. Some enthusiasts saw the refurbishment as vandalism of a popular class of tram. However, over the course of time, the Millennium trams settled down and provided reliable service following a few initial teething troubles (which was to be expected really). 707 did not have opening cab windows originally and had air conditioning units in the driver's cab. For a few months after entering service, a fitter could be seen at Manchester Square with a watering can to top up the water in the air conditioning unit!!!!, needless to say, an opening cab window was installed soon after. During 2010 and 2011, the tram received modifications with the fitting of pods and power operated sliding doors. The promenade was very busy with standing traffic on both sides of the road. It was like the middle of the summer season. The council’s decision to keep the Illuminations on until Jan has certainly paid off and is to be repeated in 2022. It was quite surreal to see the amount of people around at this usually deserted time of year. We managed to get through the Starr Gate depot on the access loop this time which was a bonus for folks who had missed the earlier leg. Back to Rigby Road depot at the end of the day shows a varied line up HMS Blackpool F736 required a depot shunting manoeuvre before heading out for an Illuminations tour. The pantograph lights up the area with a flash from the overhead. Some pics now from the New Year’s Day Chester and Wrexham Running Day: It was a chance to go back in time to the glory days of bus travel whether on a Crosville bus remembering the good old days of the area, or on a London bus imagining you’re travelling down Regent Street. Two routes were on offer both starting from the Wrexham Road Park & Ride. One went into Chester and the other to Wrexham. Bristol LH – OJD 93R (BL88). New to London Transport in April 1977. Allocated to various garages including Hounslow, Kingston and Croydon. Passed to OK Motor Services in 1981 where it remained until 1997. Rescued from North East Bus Breakers for preservation. Goes like a rocket too!! Bristol RE – UFM 52F (ERG52). New to Crosville’s Liverpool Edge Lane depot in 1968, later passing to Rock Ferry depot. Spent most of its time on various excursions into North Wales. Moved to Caernarfon depot in 1972 for use on the famous ‘Cymru Coastliner’ service linking Caernarfon and Chester along the North Wales coast. Bristol Lodekka – 4227FM (DFG157). New to Crosville in 1964, and based at Wrexham depot. Operated service D1 between Llangollen, Wrexham and Chester. This bus worked the very route back in the day that it was on at this event! Withdrawn in 1981. AEC Routemaster – WLT 765 (RM765). New to London Transport in April 1961 to their Edmonton garage. Like all RM’s, during its working life it paid regular visits to the LT Overhaul Works at Aldenham. Its first overhaul was in 1965, followed by others in 1968, 1972, 1975, 1977 and 1980. It saw service at Stamford Hill, Catford, Holloway and South Croydon garages before withdrawal in 1998. Continues below:

-