-

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Days Won

184

Everything posted by Roy B

-

Final Focus 32 leads the field away. 515 pulls off in turn 3. 34 & 491 go around at the entrance to the backstraight. 197 & 16 are the quick men from the back. Ryan taking an outside line through turns 3 & 4 pulls clear of Mat. 197 fires 276 and 502 in hard to the turn 1 plate resulting in a caution. 16 & 53 pull off before the restart. 127 leads away at the green. 235 feels the force of his car builder's front bumper as they enter turn 3. Ryan leading at halfway. 127 in second gets a flat right rear with 4 to go. 21 & 326 pull off. 197 crosses the line for his 100th race victory.

-

Consolation Catch Up 515 loses the left rear wheel entering turn 3 on the opening lap. 448 and 268 tangle and collide with the rear of the stationary 515 car on the run off area. 235 leads off the restart. 212 slows entering turn 4 and pulls off. 345 comes to a stop in turn 4 with smoke coming from the left bank. 16 leads from 326 and 276 until Mat also slows and pulls off at halfway. 20 puts a big hit in on 276 entering turn 1 which collects 548. A couple of laps later Sarge comes up behind the slower 548 which delays the 326 car. This sets the stage for a classic last bender from 20 who fires a big'un in going into turn 3. Mark rides out the hit and tries to force Liam onto the inside kerb. However, he has lost power from the hit and has to watch as the 20 takes the win. A great finish!

-

Heat Two Happenings 44 leads away. 587 takes off around the outside of turns 1 & 2 to move into the lead. 515 the first to show from the back. 212 pulls off after sparks appear from the left side of the engine whilst powering down the backstraight. 515 also slows and pulls off a few laps later. 587 stops on the outside of turn 2 with 5 to go. 1 taking the faster and smoother outside line through turns 3 & 4 moves to the front. 326 stops in a cloud of steam at the end of the backstraight on the last lap before crossing the line.

-

Hi folks, Welcome to Odsal Heat One Happenings 32 leads the field away before an early spin in turn 1. 197 eases 53 aside entering turn 3. 276 now leading tangles with 216 on the backstraight letting 345 into the top spot. 20, 211 & 502 pile up in turn 2 bringing out the caution. The restart sees 197 take the lead from 345 who pulls off a couple of laps later with steam coming from under the bonnet. 249 doesn't make it easy for 16 to come through for 2nd. With 3 to go 16 pulls off with a smoky engine. King John has the right rear let go with 2 laps left but continues for a 6th place finish.

-

King's Lynn - F1 Stock Cars, Results 19/3/22

Roy B replied to calamity507's topic in Essential Information

Pics in the gallery -

King's Lynn - F1 Stock Cars, Results 19/3/22

Roy B replied to calamity507's topic in Essential Information

Final Focus 32 leads away. 289 & 20 tangle and bounce off the homestraight fence. 127 & 73 clash in turn 3. 12 & 197 have a big moment entering the homestraight which sees Ryan sideways. 20 hits 259 hard into turn 1. 191 & 150 once again are flying through the field. 191 suddenly slows and pulls off. 515 gives 289 a big hit into turn 1. 73 and 150 have a coming together exiting turn 4 which sees Chris half spin. Caution period. 32 still leads. 496 holds up 150 who promptly launches him into the turn 1 fence. Both pull off soon after. 197 takes 515 into turn 2 for 2nd. 587 is flying at the front as Ryan gives chase. He eventually gets him just before another caution for 20 who is stranded on the outside of turn 2. 197, 587 and 515 are the top 3 on the restart. Another caution period almost immediately as 172 is upside down in turn 2. 197 takes off from the outside of turn 4 on the restart and leaves the rest behind. A high speed trio of 515, 587 and 289 circulate behind. Ryan plays with the throttle as he blasts down the backstraight for the last time. A master class from the Boss. That's it from me folks. Back from Odsal 👍 -

King's Lynn - F1 Stock Cars, Results 19/3/22

Roy B replied to calamity507's topic in Essential Information

Consolation Catch Up 150 and 175 clash in turn 4. 216 & 319 tangle and spin in turn 4 next lap. 45 stopped on the outside of the turn 2 to backstraight line. 545 broadside on the homestraight. Caution period. 526 pulls off with a flat front right. The restart sees 414 & 169 at the front of eight red tops. 1, 191 & 150 break through to the front. 150 spins out exiting turn 4. 20 hits 175 entering turn 2 and spins out. 1 by now leading starts to slow with evidence of smoke coming from under the bonnet. 191 takes the lead but then hits a stationary 319 in turn 2. 1 retakes the lead with 16 on a charge close behind. Entering turn 4 for the last time Tom gets baulked by 548. Owing to the problem with the car he is unable to accelerate in time to stop Mat beating him over the line. -

King's Lynn - F1 Stock Cars, Results 19/3/22

Roy B replied to calamity507's topic in Essential Information

Pit News 526 - Finn on the hunt for a replacement battery. 16 - Suspect gearbox problem. 515 - Oil pipe burst. Engine all ok. 345 - Loading up. Engine blown. 259 - Replacing bent link rods on the front left. 1 - Chewed a belt. A big box of assorted sizes being searched through for a replacement. -

King's Lynn - F1 Stock Cars, Results 19/3/22

Roy B replied to calamity507's topic in Essential Information

Heat Two Happenings 32 leads away. 526 & 16 pull off on the rolling lap. 150 & 197 are the quick men through from the reds. They engage in battle until Ryan makes it past and heads off to the win 515 takes 150 on and gets ahead. 44 half spins 515 in turn 3. 150 takes a wayward line down the backstraight after encountering a slower lap down car. The World Champ in the 220 car ends up colliding with the side of 150 and they end up in the turn 3 fence. Both get going together and race side by side for a lap until 1 pulls away. 515 starts to emit smoke from the left side of the engine. This gets worse as the laps wind down. He makes it over the line for 2nd place and as he slows flames appear from the engine bay. The extinguishers are soon on the scene to put it out. -

King's Lynn - F1 Stock Cars, Results 19/3/22

Roy B replied to calamity507's topic in Essential Information

Hi there folks, We're back. Welcome to the 2022 season. W & Y Race Recap 496 leads away the field. 234 & 373 tangle in turn 1. 496 breaks away up front as 326 comes through fast from the blues. 45 holds off 326 for a couple of laps. 345 pulls off. A slow moving 524 gets clobbered by Nige at the end of the homestraight which sees 45 half spin. In the closing laps 407 gets in the way of race leader 496 which allows Sarge to blast through for the lead and the race win. -

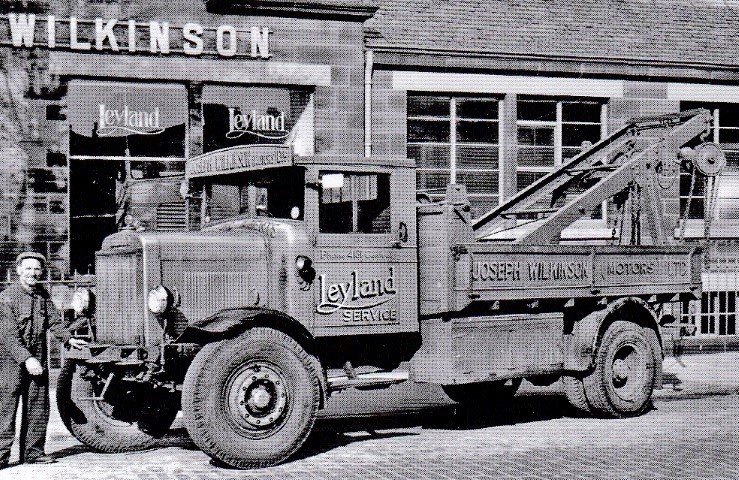

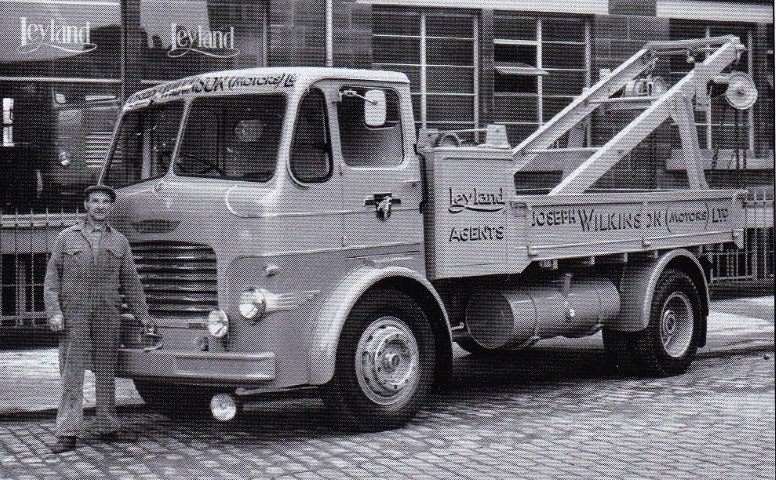

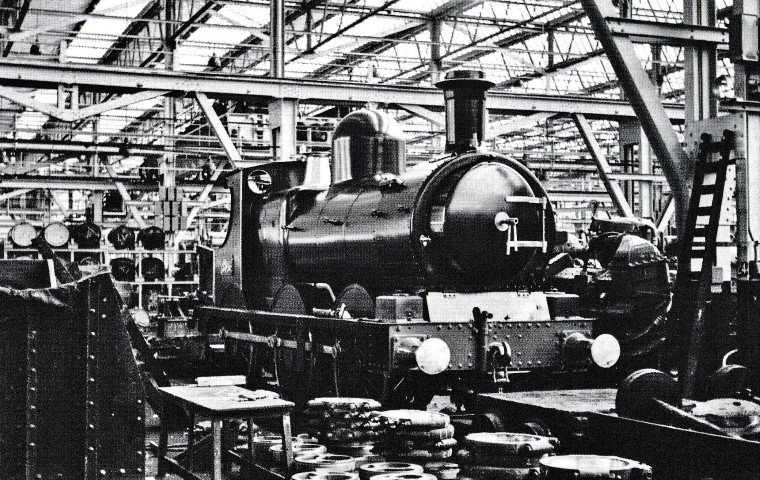

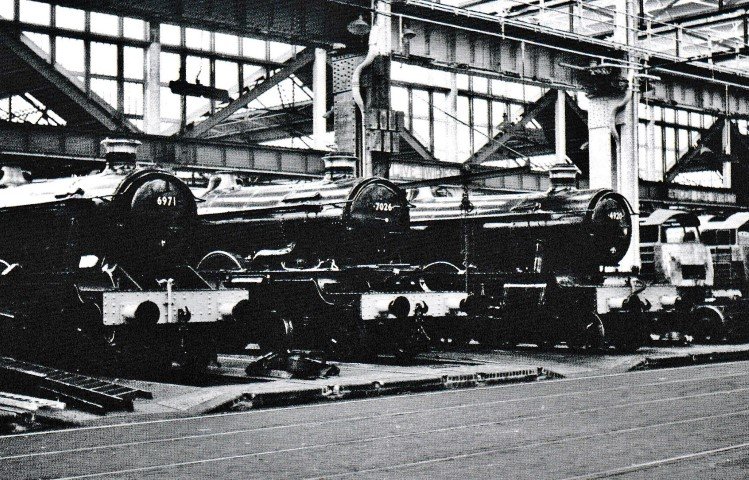

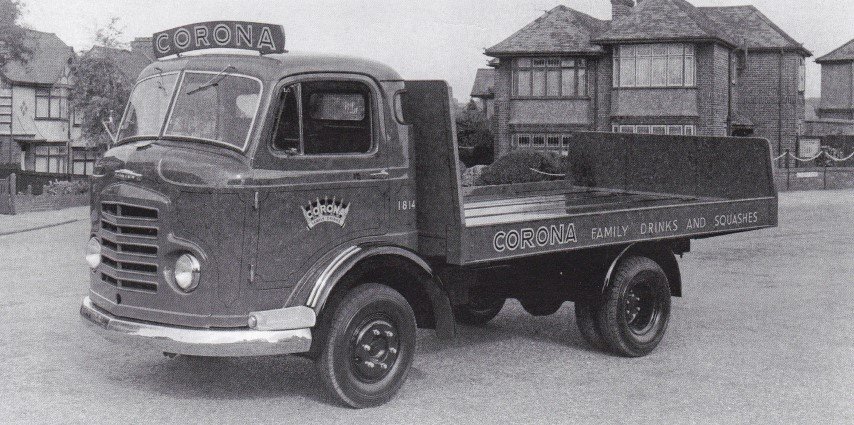

Continues from above: Miscellaneous Pics This Leyland Bison was the original breakdown wagon for J.Wilkinson’s of Edinburgh This newer Beaver was later fitted with its winch and was still in use well into the 1970s. I bet Joe Reid, the chap in both photos, had plenty of stories to tell about his time with these wagons! Although at first glance this looks like a Leyland Steer, it is in fact a 12.B/1 Beaver, with an additional steering axle fitted. NTD 242 was a 1951 chassis new to Walter Southworth, Rufford, Lancs, in the February of that year. When brand new this coach was used on the MX5 service to Leicester. It is former United Counties No 278 (TBD 278G) a 1969 Bristol RELH6G with ECW body. Offside showing the single rear window, boot, emergency door in the second bay from the back and separate reversing lamp. Leigh 15 (PTC 114C), a 1965 East Lancs bodied AEC Renown. Leigh favoured lowbridge/lowheight buses as a result of a significant number of low railway bridges in the town. The interior of Swindon Works in early 1962 with 1897 vintage “Dean Goods” number 2516 being prepared for exhibition in the first Swindon Railway Museum which opened later that year Swindon Works ‘A’ Erecting and Machine Shop in 1962, with Class 52 diesels being built alongside the steam overhauls A Commer QX platform lorry for Bulmer’s Cider. The steel ‘cage’ body sides were there to prevent casks of cider going AWOL, while the deeper side rave to the platform provided space for some bold signwriting. The body was built by Abbots of Walsall. Like ‘R White’s Lemonade’, ‘Corona’ is no longer to be found in British shops and generations of young entrepreneurs can no longer make some extra pocket money by ‘collecting’ deposit-returnable glass bottles and taking them back to the shopkeeper. This little Karrier Bantam, still to be registered, but according to the signwriting, number 1914 in the Corona fleet, would soon have been loaded high with wooden crates, carrying bottles of different flavours of the popular ‘family drink’. It’s just as well that the government allowed Karrier to produce ‘Utility’ trolleybuses during the war, as South Lancs Transport ran one of the few electric interurban passenger transport networks. FTD 453 was number 61 in the South Lancs fleet and although the Utility body was devoid of curves, it still looked quite handsome. Lastly some pics from St Day on Sunday (13 Mar): Dave Sansom wrote his bolt on front bumper off on Matt Westaway’s car last meeting. He’s gone back to his favoured welded on job. Josh Weare’s new paint Aaron Vaight was awarded four bottles of Rattler cider as reward for the commitment on being the furthest travelled again After the customary grand parade the cars backed up to the fence to salute Crispen Rosevear receiving an award of Special Recognition for his endeavour’s to save St Day A brace of wins for the Semtex Kid Joe Marquand won the Voice of Autospeed Trophy for the second time in his career That’s all folks for this off-season. Thank you for viewing. We’ll meet again in November all being well. Have a good season’s racing. Back from King’s Lynn with pics/updates etc.

-

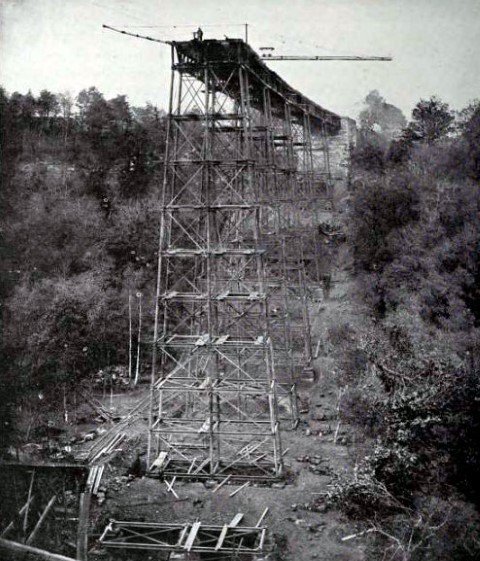

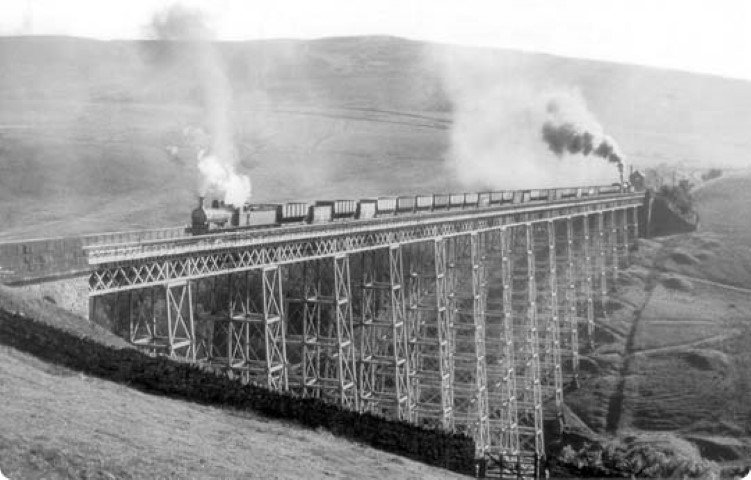

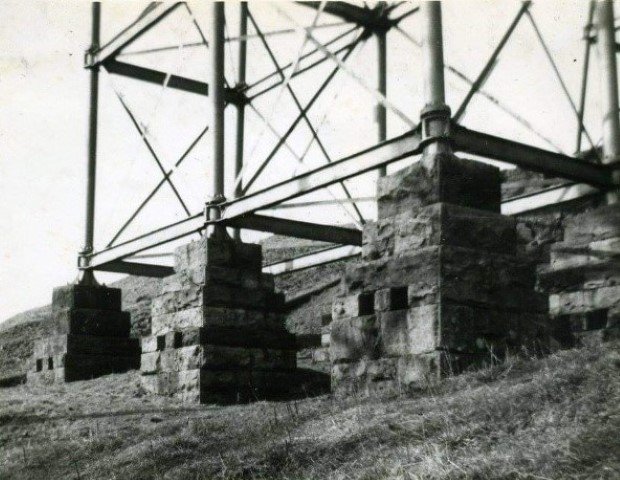

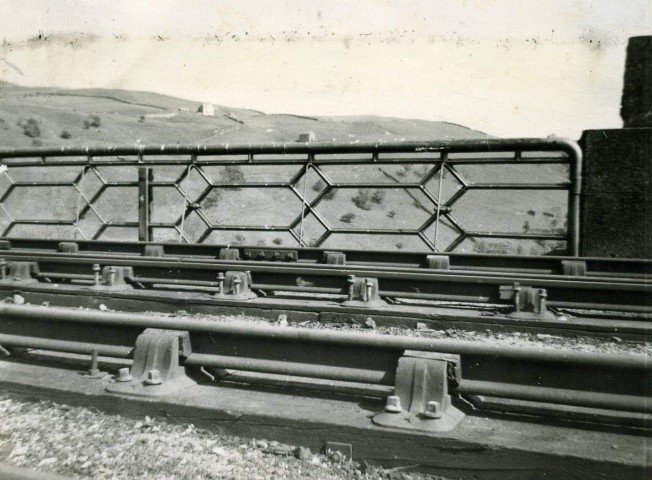

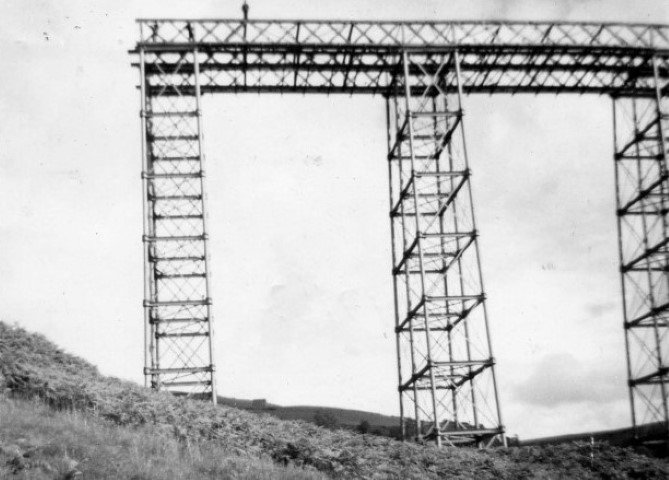

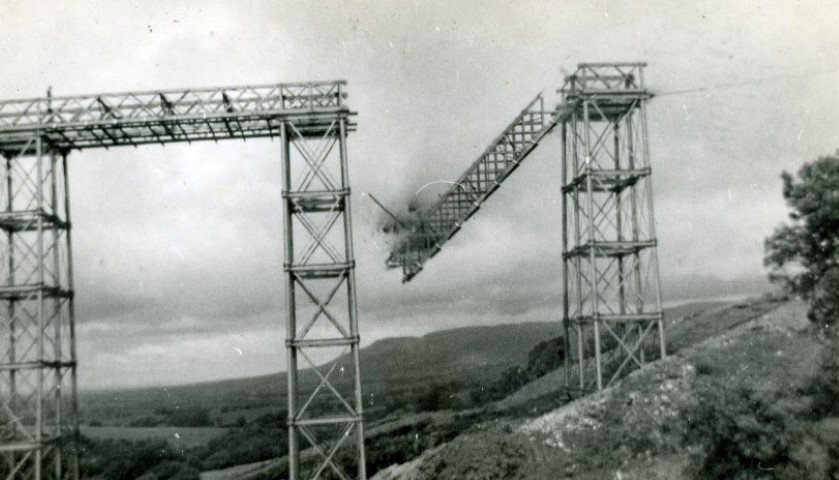

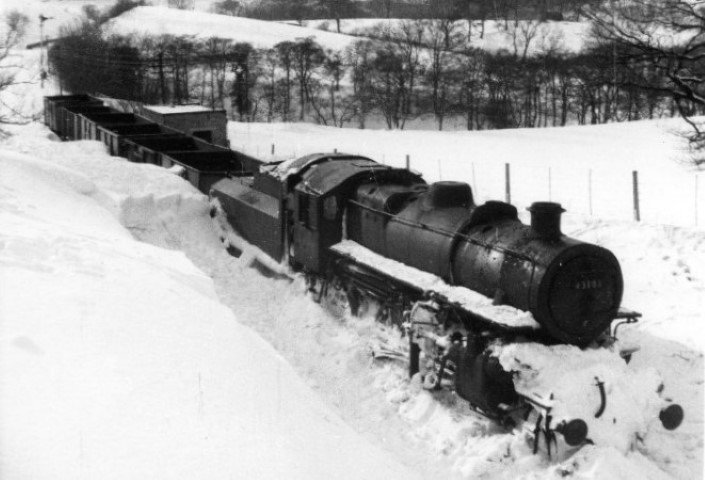

Continued from above: Let’s head north now to Barnard Castle in Teesdale, a historic market town which takes its name from the castle around which it grew. The castle was named after its 12th Century founder, Bernard de Balliol, and was later developed by Richard III whose boar emblem is carved above a window in the inner ward. The castle looks down to the tumultuous River Tees below. In the centre of the town stands an octagonal building, the Market Cross known locally as the ‘Butter Market’, built by Thomas Breaks and given to the town in 1747. Two bullet holes in the weather vane are reputed to be the result of a shooting competition between a volunteer soldier and a local gamekeeper in 1804. One of the railway companies that served the town was the SD&LUR: The South Durham and Lancashire Union Railway was a courageous transport initiative of the 1850s. Conceived as a vital transport artery to bring essential supplies of coke to the new iron furnaces of Barrow-in-Furness, it was planned to cross the Northern Pennines at Stainmore Pass (1370 feet above sea level), since Roman days an important highway – as it still is, now as the A66 trunk road. Initially the railway was also to haul the rich red hematite iron ores of Furness back to the iron furnaces of Teesside, but this traffic was soon displaced when rich ore deposits were discovered in the Cleveland Hills, only a few miles south of Middlesbrough. Supported by the industrialists of Barrow and Teesside, and by the Lancaster & Carlisle Railway, the company obtained Royal Assent for its Act of Parliament, without opposition, on 13th July 1857. It had a total authorised capital of £550,000. The Company was incorporated immediately, with John Wakefield, a Kendal banker as its chairman and Thomas Bouch as its engineer. Six contracts for construction of the line were let in 1859 and 1860. Three further contracts were let a little later for the construction of three iron viaducts: over the River Tees just west of Barnard Castle, at Deepdale one mile south of Lartington, and at Belah one mile south-west of Barras. The total cost amounted to £214,523 for 46 miles of single line railway between Barnard Castle and Tebay. From Tebay the mineral traffic was to be worked south on the Lancaster & Carlisle Railway as far as Carnforth, the Furness Railway then taking over haulage over the recently completed Ulverston & Lancaster line to Barrow. The line opened to mineral traffic on 4th July 1861, and for passenger services on 8th August 1861, with two trains a day in each direction worked by the Stockton & Darlington Railway. From 30th June 1862 the SD&LUR was absorbed into the Stockton & Darlington Railway, this in turn merging into the North Eastern Railway from 13th July in the following year. Traffic was soon putting heavy demands on the route, as the Furness iron & steel industry mushroomed. The special suitability of Cumbrian ores for the early Bessemer steel production gave it a short-term dominance of the industry, and works were also established at Millom, Askam, Ulverston and Carnforth. Via the Eden Valley Railway from Kirkby Stephen to Penrith, and the Cockermouth, Keswick & Penrith Railway, coke was also supplied over the Stainmore line to the multiplying works around Workington. In total, around one million tons of coke a year were being carried over Stainmore in the 1880s. Progressively, between 1870 and 1889 authority was given by the North Eastern Railway board for the line east from Kirkby Stephen to Barnard Castle, and from Sandy Bank near Ravenstonedale to Tebay to be doubled to carry this immense traffic. Loaded trains had to be hauled to Stainmore Summit from Barnard Castle up gradients as steep as 1 in 67, 1 in 69 and 1 in 68 successively over a distance of 13 miles. The ten mile descent to Kirkby Stephen was even steeper, long stretches having gradients of 1 in 59 and 1 in 60, with 1 in72 over Merrygill and Podgill Viaducts. Well before the end of the 19th century the dominance of Bessemer steel was over, and a long slow process of decline had begun. New coke-making plants around Workington made inroads into the West Cumberland coke traffic from about 1910, and it ceased altogether by the mid-1920s. The coke traffic to the remaining Furness area works at Millom and Barrow was diverted to run via Carlisle from July 1960, and the Barrow works ceased making iron and steel soon afterwards, Millom lasting a few more years until 1968. With little more than a very sparse passenger traffic remaining, closure of such an expensive route, in terms of both maintenance and operation, was inevitable, and the end duly arrived on 22nd January 1962, though the line was retained from Appleby through Kirkby Stephen to Merrygill for quarry and local coal traffic, until the mid-1970s. Join me now as we take a look at a couple of locations (the Deepdale and Belah Viaducts) on this former line as it heads west away from the town towards Tebay. Our first stop is the site of Deepdale Viaduct. Leaving the town it’s a 45min walk following the Deepdale Beck through Deepdale Woods until we come to the northern abutment in amongst the trees. The cast and wrought iron viaduct, opened in 1861, was designed by Thomas Bouch. Sir Thomas Bouch was a British railway engineer in Victorian Britain. He was born in Thursby, Cumberland, on 25th February 1822 and lived in Edinburgh. As manager of the Edinburgh and Northern Railway he introduced the first roll-on/roll-off train ferry service in the world. Later, as a consulting engineer, he popularised the use of lattice girders in railway bridges. Bouch later set up on his own as a railway engineer, working mostly in Scotland and Northern England. Lines he designed included several between the Northeast and Cumberland, including the South Durham and Lancashire Union Railway, from a junction near West Auckland via Barnard Castle, over Stainmore via Kirkby Stephen to a junction with the West Coast Main Line at Tebay. This was 50 miles of railway, completed in 1863. He made considerable use of lattice girder bridges, some with conventional masonry piers and others with iron lattice piers. The most notable examples of iron lattice piers were the Deepdale and Belah Viaducts. The two works were contracted to Messrs Gilkes, Wilson, and Co., of Middlesbrough, and Mr Kinnaird, the builder of the Crumlin viaduct. Messrs Gilkes, Wilson and Co. also contracted with the company for the construction and erection of another wrought iron viaduct, 200 feet in height and from 900 to 1,000 feet in length, over the river Belah. Both these viaducts were to be similar in character to the celebrated Crumlin one, and supported upon compound metal columns. Their contracts (for iron-work only) amount, to £12,700 for the Deepdale structure, and £16,500 for that over the Belah; that of Mr Kinnaird amounting to £7,600. Mr Appleby, who built the Barnard Castle station, contracted for the foundations of the Deepdale and Belah viaducts,—his whole undertaking amounting to nearly £16,000. Incredibly, the viaduct was built in just 80 days by a team of 60 men, putting together pre-fabricated sections of the metalwork. Some years later a report from 16/12/1903 states that a platelayer was injured at Cat Castle: “For some time extensive restoration work has been going on at the Cat Castle, or Deepdale Viaduct, which is over 160 feet high. The rails have been disturbed and new metals laid. In consequence all trains, either on the up or down line, are switched on to one set of rails, and great care is exercised in signalling. All trains slow down on approaching Cat Castle, and on Saturday, Joseph Chatt was told to give warning. He had indicated the approach of the morning train from Barnard Castle to Tebay, when, in stepping out of the way he was caught by the passenger train engine, and knocked down. His arm was broken and besides the shock he sustained other injuries, the poor fellow having been hurled on to a heap of chains, where he was found to be in a semi-conscious condition. Escape from a terrible death was miraculous. The driver informed the other men, who went to Chatt's assistance”. Another from 14th January 1914: “Local interest at this moment is concentrated on the possible reconstruction of the three colossal viaducts on the South Durham and Lancashire Union Railway, namely, the Tees Viaduct, 732 feet long; the Deepdale or Cat Castle Viaduct, 740 feet in length; and the Belah Viaduct, 1,000 feet long. The contract is already let for reconstructing the Tees Viaduct, to the Motherwell Bridge Company, Limited, having secured the work, and the undertaking will be commenced in the early summer. While the viaducts between Barnard Castle and Kirkby Stephen are quite capable of carrying present-day railway loads, the North-Eastern Railway Company, as a precautionary measure, have withdrawn from service over this route their specially-designed heavy eight-wheeled coupled locomotives, built for mineral haulage from the South-West Durham coalfield to the iron and other manufacturing centres of North Lancashire and Cumberland. Meanwhile the mineral trains will be drawn by six-wheeled coupled engines. A day or two ago, acting on the instructions of the company's engineers, holes to the depth of about seventeen foot were dug in the neighbourhood of the Belah Viaduct by way of testing accurately the stratification, and boring operations, it is understood, will later be carried cut. The Deepdale Viaduct has also been examined as to rock foundation“. 1925 “It took 21 tons of paint to repaint Deepdale Viaduct, and 31 tons for Belah. Ten men were on the job for three months”. 10/06/1931 “Barnard Castle in the past earned a reputation in producing big throwers of the cricket ball. William Lawson, when a young man used to emulates his athletic feats by throwing a stone over the Deepdale Viaduct, which was a considerable height”. Consisting of 11 spans totalling 740 feet, the structure crossed Deepdale beck at a height of 161 feet. Closure of the line came in 1962 and the viaduct was dismantled a year later. The viaduct was dismantled in 1964 As it is today. The far abutment is arrowed far off in the distance. To the north side are the remains of the signal box. The track bed was used to access Cat Castle Quarries off to the back left which are now disused. Looking south to the site of the viaduct After returning to Barnard Castle it’s a short trip west to Barras. It is a hamlet close to the River Belah, about 4 miles south-east of Brough, Cumbria. Until the creation of the new county of Cumbria, Barras was situated at the eastern edge of the historic county of Westmorland. From 1861 until 1962 it was served by Barras railway station on the Stainmore line between Kirkby Stephen and Barnard Castle. The scenery and views around here are breathtaking. It is a short 15min walk to get back to the track bed as it makes it way south towards the site of Belah Viaduct. Part of the track bed is on private farm land so i paid a visit to the farm to see if it would be possible to access it. They couldn’t have been more helpful, and also told me the location of a culvert that runs through one of their fields. It was built by the railway company to allow Swine Gill to flow underneath the track bed. Just look at the perfect arch. Each stone block shaped to fit by the stonemasons. British engineering at its best. At the end of the cutting the view opens out to reveal a scene of magnificence beyond compare The air gap at the site of the Belah Viaduct Taken from the same spot in 1950 as BR Standard Class 4MT 2-6-0 No 76045, and an Ivatt LMS engine of the same type cross the viaduct with a Blackpool to North-East service “Good grief!” exclaims Nigel Carmichael as his jaw hits the floor. From the lofty vantage point of a Cumbrian hillside, the retired Signal and Telegraph man peers down on two stone abutments which sit forlornly either side of the valley like a pair of forbidden lovers. When he was last here almost 50 years ago, the air gap between them was occupied by the iron leviathan that was Belah viaduct. But no longer. “It’s just empty, gone, nothing!” Belah was the centrepiece of an ambitious trans-Pennine connection between Barnard Castle and Tebay, involving a tortuous climb up to Stainmore summit, 1,370 feet above the sea. Construction of the wrought and cast iron viaduct got underway in November 1857 when Henry Pease, the new Member of Parliament for South Durham, laid the foundation stone. Costing £31,630, contractors Gilkes, Wilson & Co erected Belah in a little over two years. At 196 feet, it was the tallest bridge in England. Freight wagons first pressed the sleepers of the 46-mile single line on 4th July 1861, with the passenger service inaugurated one month later. Two trains per day ran in each direction, operated by the SD&LUR. It was a period of managerial upheaval. Within a year, the line had been absorbed by the S&D which, in turn, was taken over by the North Eastern Railway in 1863. Traffic levels exceeded all expectations, so much so that the route struggled to cope with the insatiable hunger of Furness’ burgeoning iron and steel industry. As new works sprung up around Workington, the burden grew heavier. The NER board responded in 1870 when authority was granted for the line to be doubled. Within a decade, the annual haul of coke heading west over Stainmore reached one million tons. Those loaded trains felt the strain as they laboured optimistically to the summit. The 13-mile climb from Barnard Castle was rarely flatter than 1 in 67 whilst the ten-mile descent towards Kirkby Stephen was even steeper, with one section falling by 1 in 59. The line’s success mirrored the fortunes of its engineer. In 1854, Thomas Bouch had submitted a proposal to bridge the Firths of Tay and Forth to directors of the North British Railway. It was dismissed as “the most insane idea ever to be propounded” but, by 1870, the case was overwhelming and work finally got underway on a crossing of the Tay in January 1873. Bouch was at the helm. It was Britain’s largest single engineering project and, at over two miles, comfortably the longest construction anywhere in the world. The undertaking was beset by problems. Surveys had indicated a foundation of bedrock but gravel was found instead. Bouch hastily redesigned the structure to lighten the load. Six men died in an underwater chamber. One of the main girders succumbed to the weather and fell into the river. And yet, despite these setbacks, the bridge was completed just a few weeks behind schedule and passed a painstaking inspection by the Board of Trade. In June 1879, a year after it opened, Queen Victoria crossed the water on Bouch’s bridge and duly rewarded his endeavours with a knighthood. The events of the following winter were tragic and well charted. On Sunday 28th December, both the bridge and a train plunged into the Tay during a violent storm, claiming 75 lives. The subsequent inquiry placed the lion’s share of blame at Bouch’s door, bringing his career to a screeching halt. He died four months after the verdict had been delivered. Belah though was still standing and did so for 102 years. As the 20th Century opened its doors, the NER was running five trains either way across Stainmore, connecting Barnard Castle with Tebay in three-quarters of an hour. Specials ran at holiday time through to Morecambe and Blackpool. Durham miners enjoyed the view down the Eden valley en route to their union’s convalescent home in Ulverston. Like many others, this community service was forced to surrender to the howling blizzards of 1947. In early February, a Darlington-bound night train foundered near the summit. Passengers were transferred to the trailing carriage which was uncoupled and hauled back to Kirkby Stephen. For eight weeks, clearance teams fought the biting weather, assisted by Army flame throwers and a pair of rail-mounted jet engines. Victory was eventually secured by shovel power and elbow grease. For seven years during the fifties, the unenviable task of keeping Stainmore’s linewires well connected sat on the shoulders of Nigel Carmichael and his mate Albert. Based at Barnard Castle, this pair of adventurers toured the railway by train or Wickham trolley, looking after the signal and telegraph equipment. This often involved working at heights, for which Albert was not well suited as he had a fear of them. Their patch extended up a branch line to Middleton-in-Teesdale and across the Pennines to Merrygill signalbox. Life in the open air had much to commend it, though its appeal withered during those harsh winters. “It became a completely different world” shivers Nigel. “There used to be a lot of faults - telegraph wires coming down. And that was my job - to climb the pole. My mate used to pull the wires up and I had to join them. Your fingers were frozen! However, you got over it and it got warmer the longer you were up there. Except the toes - they were always cold!” Belah was a regular haunt. They’d travel up to Barras and walk the last mile, crossing the viaduct to the signalbox by the western abutment. A handful of telegraph wires ran the length of the structure, supported on three-foot long arms extending out from the northern side. A copper binder attached the wires to insulating pots but sometimes, in strong winds, the binder would break and the wire swing out over the drop. “If the furthest one went, we’d get a stick to try and hook it back. Sometimes i used to go out onto the arm. You never looked down! They provided safety belts but we didn’t use them. You never thought about falling - all you were interested in was getting those wires through and the job completed.” When a train came, the girders would rumble and shake a little, “especially if you were out on those arms and couldn’t get back. The signalman would shout “what the hell are you doing there!’” Nigel delighted in Stainmore’s wildlife, particularly during springtime when the birdsong was at its sweetest. He played delivery boy for one of the signalmen who had a profitable sideline catching rabbits to feed his friends in Barnard Castle. Peewit eggs were also a favoured delicacy. One day he looked down from the girders to see the Belah hounds in pursuit of a fox, closely followed - on foot - by the huntsmen and a handful of platelayers. And a chap called Moscoff once tried fishing from the viaduct. “He had this long line weighted by a great big stone so the wind wouldn’t blow it too much. He didn’t catch anything!” Despite its isolation, Nigel and Albert were rarely alone. A permanent way gang of a dozen men fettled the track down from the summit. They were often around. And three girls from a remote farm (the very farm i called at) used the track as a walking route to Barras station, where they caught the bus to school. The livelihood of our S&T duo came under threat as the decline of Britain’s railways gathered pace in the late fifties. “I heard rumours that the line was going to close so I thought i’d better get another job at Darlington.” Proposals to withdraw Stainmore’s passenger services spoiled the Christmas party of 1959. Local forces were marshalled and a petition marked the start of a vociferous campaign, aimed at securing a reprieve. Ultimately the quest was futile. The remaining coke traffic was soon diverted via Carlisle although the line’s new diesel units continued to carry travellers for another couple of years. The closure programme finally claimed Stainmore on the 20th January 1962. Four hundred enthusiasts jemmied themselves onboard a double-headed steam special, bedecked with a wreath and accompanied on bagpipes by the melancholy sounds of Auld Lang Syne. It was the end of the line for Belah. Piece-by-piece, in an act of extraordinary vandalism, its ironworks were dismantled and salvaged for scrap. A year after the axe fell, one of the railway’s greatest engineering masterpieces had been cut from the landscape. Part of the route still clings to life through the exploits of volunteers from the Eden Valley Railway, who operate tourist trains between Appleby and Warcop. Their official aim - though clearly a pipe-dream - is to relay track across the moors and reconnect Barnard Castle with the railway network. This mind-boggling aspiration would involve a £25million investment at Belah. For those who can’t wait for pigs to fly, three survivors of Belah’s past await the attention of folk on Shanks’ pony. Two colossal abutments - notable feats in themselves - still mark the extent of the former span whilst the tattered remains of the signalbox, abandoned by the maintenance men, have withstood the ravages of forty Stainmore winters. Footpaths pass beneath these relics, within 400 yards of public, if rather minor, roads. As Nigel muses, “I thought this railway would last forever but, with modernisation, it’s all gone.” And the Belah valley is palpably poorer for it. A bit more detail on the construction of the viaduct: The viaduct consists of 15 piers of varying heights, according to the section of the valley, each pier being composed of six hollow columns, placed in the form of a tapering trapezium and firmly braced together with cross-girders at distances of 15 feet perpendicular, and by horizontal and diagonal wrought iron tie-bars. A view of Belah viaduct, showing the base of the fourth pier. The 12" columns rested on the stone foundations. Each column was fastened onto the stones with four massive bolts which passed through all the stone work and were held in place by a metal wedge at the third stone from the bottom. You can see the inspection holes. At the top, the bolts were screwed onto the metal plates of the columns. It is a distinguishing feature in this viaduct, that the cross or distance girders of the piers encircle the columns which are turned up at that point, the girders being bored out to fit the turned part with great accuracy. No cement of any kind was used in the whole structure, and the piers when completed, and the vertical and horizontal wrought iron bracings keyed up, are nearly as rigid as though they were one solid piece. The rails are carried by longitudinal baulks the whole length of the viaduct; and guard rails are fixed on both sides, so as to render it nearly impossible for the wheels of an engine or carriage to get off the way. The whole is surmounted by an elegant hand-railing of cast iron in which the design of the viaduct is well maintained. The weight of the whole viaduct is: cast iron - 776 tons; wrought iron - 598 tons; the superstructure contains 12,843 cubic feet of Memel timber. One important element which has to be provided for in these erections is that of expansion, which in such a length as the Belah - 1,000 feet - would become a serious difficulty if it were not arranged for. This has been done by the application of sliding plates lined with brass, on which every third girder rests, with liberty to move in its length within certain limits. The expansion of these girders which are secured together is thus provided for at one joint; and experience has proved that this is sufficient, as the girders move easily without producing the slightest effect on the piers. The total length of this viaduct is 1,000 feet, and the greatest depth from the rail to the ground 195 feet. It was erected in the incredibly short space of four months by Messrs Gilkes Wilson and Co of Middlesbrough-on-Tees. A stone viaduct over the same spot would have occupied three years in its erection. Much of this quickness was, however, attained by the admirable arrangements made by this firm for the fitting and erection of the work. The fitting and finishing of the work was carried out with the utmost mathematical accuracy. When the pieces of the viaduct had to be put together at the place of erection, there was literally not a tool required, and neither chipping nor filing to retard the progress of the work. The mode of erection adopted was novel, but remarkably successful. They used no scaffold, but having prepared a crane, with a gib of sufficient length to reach from the abutment over the first pier, and, of course, from the first pier over the second, and so on, they commenced the erection by setting the first pier from the abutment, on the Brough side of the valley. The crane was balanced by a shifting weight box so that each piece of the pier, whether light or heavy, was counterbalanced as it swung; and they were thus enabled to lower it slowly and steadily to its place, whilst it was swinging round from the point of its first suspension. As soon as the first pier was erected, they placed two baulks across from the abutment to the pier, and ran the girder (which was placed on two low bogie wagons) over, dropping it into its place with the assistance of the crane, by which each end of each girder was lifted and lowered. On the completion of the first span the crane was moved forward, and the erection of the second pier was commenced; and this process was pursued with singular success, not a single accident occurring during the whole erection, and not a man receiving any injury - a fact almost without parallel in the annals of railway engineering. Some planks were placed upon the cross girders, which, with some hand ladders, enabled the workmen to go up and down readily. In the erection of this important work there were about 180 men engaged. For me that was a remarkable engineering feat in such difficult terrain. The black and white pic above was taken from the gate arrowed here Check rails and stretchers as strengthening against the wind, and the vastness of the distance could be daunting on a foul weather day. The following pics show some of the viaduct’s dismantling: 8am, Monday, 3rd June 1963, looking towards the Kirkby Stephen end of the bridge. The demolition men would arrive the following day. 4th June 1963. Two parties arrive at the Barras end of Belah viaduct. The JCB is with the British Rail lads to remove the signal line left on Belah’s decking, while the lads from Golightly begin to trundle to the Kirkby Stephen end of Belah to start removing the decking. The bulldozer is carrying the acetylene bottles. A photograph taken at the Barras side of Belah viaduct, showing the third and fourth piers. Looking carefully you can see the men working on the top of the girders! It’s a long way down! 9/7/63. The second pier awaits its fate. This is the Barras side. The second pier being pulled over, you can just see the hawser attached to the pier, this will be fastened to a couple of bulldozers standing on the Barras abutment, in low box, giving it all they have got, as the 60ft third span gives way and crashes to the ground. 9th July 1963. “....underneath this splendid monster bridge, Shall floods henceforth descend from every ridge; And thousands wonder at the glorious sight, When trains will run aloft both day and night.” A verse found during demolition. The author was one Charles Davis. A copy of his poem had been folded and placed inside one of the columns in the course of the viaduct's construction. The bottle with the poem and a piece of paper with the signatures of all eighty men who built Belah was found in the foundations of the tallest 196ft pier. It now resides in the NRM at York. Alfred Golightly’s lads, the demolition team, have gone home....so let’s play. Members of the public posing on what’s left of the decking. Note the catwalks underneath. The icy wind whipping around the abutment has frozen the water from this field drainage pipe Let’s get across to the far side of the valley. There is another gem to see over there. It’s a slog though as it’s a steep drop down, and sharp climb up the far side. Fortunately the farmer has constructed a bridge across the River Belah. The bolts holding the main 12 inch columns to the base stones, had the heads burnt off. At the top, the demolition men cut through the main girders to within, half an inch, a hawser was fastened to the top of the girders, bulldozers pulled the hawser, and the pier was pulled over bringing the 60ft span with it. No dynamite at all....... The picture shows the bolts being cut on the fifth pier on the Kirkby Stephen side. There were eight piers on the Kirkby side, and you can see from the abutment in the distance how far down the valley the demolition crews are. On the far side now and here is one of the remaining column bases. Look across to where we were before. How good is this? The remains of the signal box and the western abutment. Just as perfect as when it was built 165 years ago Three views from different times As it is today Note the bridge in the far distance In the distance you can see the supports for the bridge in this pic Here they are, but the bridge has long gone Belah Signal Box The same view now Back to Nigel and his mate Albert: Belah box was a bleak outpost, employing three men and open around the clock. The fire was always burning. Passing trains dropped off lumps of coal together with cans of water to supplement supplies from a nearby well. Nigel would sit in the window, watching the world go by and putting it to rights. Occasionally the signalman would announce “I’m going out for ten minutes - do you mind looking after the job?”, so Nigel was left pulling the levers. He’d return a couple of hours later saying “sorry, I was delayed!” Evening entertainment was laid on by an old tramp who’d set up home in an abandoned barn and appeared regularly in the box. This was the tramp's residence with the eastern abutment high above “Fantastic fella” declares Nigel. “He’d been in the Army and the Palestine police, and he’d tell these stories of his time on the road, living in haystacks! I could have listened to him for hours. He had a great knowledge - very well educated - and liked his way of life.” A fire-place visible on the upper floor Plenty of ashes still remain next to the box One last look at this heaven on earth Apart from the farmer i didn’t see another person all day. Rabbits and birdsong were my only companions. Wonderful! A couple of extra pics from the Stainmore Line: The picture shows George William Fairier, of Warcop standing on the back of one of the demolition trains, at Stainmore summit. Note his clogs and his string to keep his coat fastened! The date will be between the 23rd and 25th October 1962. It is 60 years ago this year since the Stainmore Railway officially closed. The 22nd January 1962. The bombshell of closure was first announced in December 1959. Small communities like Kirkby Stephen started to group together, and with very limited means and funds, began to fight the giant that was British Rail. The fight was short. British Rail pulled all sorts of figures and rabbits from the hat in thier desperation to close the line. At the two hearings the objectors were NOT allowed to question British Rail’s facts and figures, which were basically lies and deceit. The objectors were forced into a corner fighting a desperate rearguard, which was always going to be doomed to failure. In those days the countries transport was governed by various transport commissions who looked into all such matters as new rail links, roads links, closures etc. They also played their part in the down fall of the Stainmore line. Once the north east and the north west commission's agreed on closure, it was a totally hopeless situation for the objectors, their only hope was at the hands of The Conservative minister of transport Earnest Marples. Marples had big investments in road building companies, closure was EXACTLY what he wanted and he duly signed the death warrant for the Stainmore railway on the 7th December 1961. With lightning speed, the final train was announced to run on the 20th January 1962. In early January 1962, a meeting was held in Barnard Castle amongst those who speared headed the campaign to save the line. They wrote to Mr Marples asking him to receive a deputation, so they could convince him closure was WRONG. The unsympathetic Minister wrote back refusing all meetings...and the rest his history. Just up from Merrygill Viaduct. These guys earning their crust, giving the plough a fighting chance. A Kingmoor Yard, Ivatt sits pretty in the snow, close to the Merrygill distant signal. The plate layers cabin is clear in this photo. The picture was taken after closure of the Stainmore line. The ‘Flying Pig’ would be taking empty wagons back to Hartley quarry. A few more pics in the gallery Continued below:

-

Hi there folks, In this final one for the off season we couldn’t get more off the beaten track if we tried. We’re going into the wilds of Cumbria and County Durham to see what remains of two sections of the former South Durham and Lancashire Union Railway. Before that though we’ll start with a look at the Birmingham meeting from 16th Oct 2021 in what looks almost certain to be the last ever Brisca F2 meeting there following the council’s decision to proceed with a planned redevelopment of the site. Following that there’s a look at three south-west dates. The very first F2 meeting was on April 9th 1994. There was nothing better than watching the racing under the lights on a Saturday night here at Wheels. Since taking over the promoting Pete Gould had tidied and brightened the place up with a coat of paint, and the installation of a one way system through the pits. Part of the council’s agreement when it was written for redevelopment was that they had to find a home for the sporting activities on site. The piece of land that they offered Pete was an ex-petrol site that you’d struggle to get a dozen Ministox on. To put it in a nutshell he has been screwed. The opening event was the track’s White and Yellow Series Final with Scotsman Graham Leckie (975) picking up the spoils. Result: 975, 595, 115, 611, 390, 194, 844, 224, 161, and 976 (top 8 through to Final). The second heat was won by Jamie Ward-Scott (881) Result: 881, 251, 992, 210, 968, 605, 184, 177, 324, and 606. and Dan Fallows (581) won the Consolation Result: 581, 924, 700, 928, 976, 302, 9, 801, 161, 460, 446, and 939. The Final was a hard fought affair and for a short time looked like Harley Thackra (9) was set for the win. However, in the final few laps he lost out to Harley Burns (992) who came through for his maiden Final win ahead of Micky Brennan (968) and Fallows. Result: 992, 968, 581, 184, 210, 161, 302, 606, 924, and 324. Josh Winch (611) took the honours as the last Brisca F2 winner at the track. The race was notable for some aggressive moves and big hits from Ben Bate (161). Result: 611, 968, 184, 581, 9, 976, 324, 210, 605, and 844. Becoming overgrown at the back of the homestraight Pics in the gallery Taunton – Sunday 23rd October 2021 The Steve Rich Trophy, and St John Ambulance White Top Shield were both up for grabs for the F2s, in addition to the final of the White & Yellow grade series. Not for the first time in the recent weeks prior to this event there was a contrasting entry of cars. There were some south-west regulars who had already called time on the season, and there were some others who had their eyes firmly fixed on the next day’s meeting at St Day. Nonetheless there was a decent sprinkling of visiting drivers. Jamie Ward-Scott (881), Jon Whittaker (533), Phil Mann (53) and Aaron Vaight (184) from the north-west were joined by Jessica Smith (390) from the south-east, Jamie Jones (915) from the Potteries, and Jack Prosser (844) from the West Midlands. Although 30 cars arrived, regrettably Charlie Lobb (988) failed to progress beyond the practice session after his car came to a crunching halt against the plating, the car hitting with such force that the youngster required assistance to exit the car – a stuck open throttle being the cause. A two from three heat format was deployed with heat one doubling as the White & Yellow grade series final featuring 15 cars. Dan Abbott (232) led the opening stages, however he was soon caught and passed by a rapid looking Richie Andrews (605). With the lap boards out, third placed Julian Coombes (828) was a little over-eager to make a move on the lead two, resulting in his car spinning sideways on the pit bend and being collected by Charlie Fisher (35) who had been making good progress up to that point. The incident saw Coombes retire and Jessica Smith (390) promoted to third with the top three finishing in that order to pick up the multitude of tyres on offer. Result: 605, 232, 390, 881, 320, 460, 915, 533, 844 and 53. Heat two, by necessity, featured all the remaining star and superstar drivers but they struggled to catch the rapid lower graders, as yellow top Tristan Claydon (210) hit the front. Matt Hatch (320) and Craig Driscoll (251) tangled on the Honiton bend, and as Hatch rejoined he then spun out at the opposite end of the circuit. Out front Claydon eased out a slender advantage over Ian England (398) for the win. Result: 210, 398, 24, 667, 542, 184, 526, 35 and 915. England led into the final lap of heat three, but Driscoll launched a bold attack heading into turn three. For a moment it looked like England would spin out, but he managed to regain enough control to hold on for the win. Result: 398, 251, 210, 828, 184, 24, 542, 606, 315 and 700. The Final featured 27 cars and came under a caution within the opening couple of laps. Half a dozen cars including Abbott, Driscoll, Hatch and Fisher along with Lauren Stack (928), had all tangled in the west bend. On the restart Claydon hit the front with former British Champion Steven Gilbert (542) quickly into the top six and then on into second, but he was unable to reach Claydon at the front who continued the evening’s run of yellow graded successes. Result: 210, 542, 606, 302, 24, 667, 398, 184, 315 and 915. The Grand National saw Ward-Scott as the sole white top on the grid, needing to secure three points to overhaul Abbott for the annual St John Ambulance Brigade Shield. He led until a stoppage was required for John Brereton (948) who had ground to a halt on the outside line just past the starter’s rostrum. Vaight made swift progress to the front on the restart, and that was where he remained heading into the last lap whereupon Jon Palmer (24) took a long dive heading into the final bend. Vaight refused to be shifted and held on for the win, whilst Ward-Scott finished tenth and thus it was Abbott who received the shield and a bonus of a new tyre for his achievements. Result: 184, 24, 667, 390, 251, 210, 605, 844, 194 and 881. The Saloon Stock Cars were racing in a National Series round. A surprise entrant to the meeting was the return of Danny Colliver (698). The action came thick and fast in the opening heat, with bumpers being traded amongst the silver roof chasers in particular. This allowed Warren Darby (677) to escape at the front for the win. Top 3 result: 677, 618 and 600. The action continued apace in heat two with Darby being quickly targeted and spun around on the home straight. There then followed a couple of race stoppages with the second restart seeing another explosive opening charge into the pit bend. The unfortunate Phil Powell (199) came off worse, the car exiting the pit bend with both front and rear metal work severely damaged with the car eventually coming to rest against the infield tyres. Finally, at the end of a long race, it was English Champion Lee Sampson (428) who took the chequered flag. Result: 428, 618 and 349 Unsurprisingly the Final saw a depleted field and it was Michael Allard (349) who won the Club 21 Trophy. Result: 349, 84 and 902. The Timmy Barnes car before and after An Allcomers race saw just 11 cars make it from the pits, only two of which were non-National Series runners. Darby took his second win of the evening as the NS entrants entertainingly battled it out for the minor spots, concluding a brutal night’s competition. Result: 677, 428 and 349. St. Day – Sunday 24th October 2021 This could have been the last time, but thankfully was not. The GN Championship was being held at this meeting, along with the Old Motorcycle Club Trophy on the Final, and the Bob Netcott Trophy to be raced for in the last race of the day. Bob was Trevor Redmond’s father-in-law, and the originator of Autospeed more than 50 years ago. Forty-five years had passed since the GN Championship had been raced for here. Bill Batten and Colin Higman had shared the front of the grid that day. Roll forward to this afternoon, and two more friends and rivals shared the front row – Jon Palmer (24) and Aaron Vaight (184). The top three trophies for the race had been crafted by an ornamental metalworker. The United Downs area was once regarded as the richest square mile in the world during the peak of its tin and copper mining days and these trophies reflected the heritage of the area. The morning rain and mist had cleared, leaving the circuit bathed in warm autumnal sunshine for the large crowd present. With 28 cars in the pits a two thirds format was adopted. Jessica Smith made her track debut here Heat one doubled as the White & Yellow Series final. Adrian Watts (222) led the early laps before Adam Pearce (460) took over. Matt Hatch’s (320) chances faded when he tangled with Mike Cocks (762) on the entry to the home straight, Hatch’s car then colliding with the plating nose first. By half-distance Richie Andrews (605) was on the back bumper of Pearce and with four laps to go he was joined by Charlie Fisher (35). With all three cars line astern Fisher seized the opportunity heading into turn one with a well-judged hit on Andrew’s that was to ricochet the speedway racer into Pearce who bounced off the fence. Fisher ran home the winner. Result: 35, 605, 828, 460, 53, 572, 320, 663 and 222. The next race was the GNC. Pole sitter Palmer made a good start which saw him hit the front, the same could not be said for Vaight who found himself bundled down the field as he found it difficult to move onto the inside line. Incredibly, he finished the opening lap down in tenth place. Slotting in behind Palmer was young superstar Tommy Farrell (667). As the race moved towards half-distance it became clear that Farrell had the pace to at least match Palmer. On an open track, Farrell drew close, but as the two started to encounter back-marking drivers Farrell fell back a little. Nonetheless, he was never far from striking distance, and his chance came with five laps to go when the complexion of the race changed markedly. Marc Rowe (526) and Paul Moss (979) hooked bumpers on the back straight and then tangled in a jack-knife in turns three and four with the leaders about half a lap behind. Josh Weare (736) clattered into Moss, but as the lead duo entered the pit bend, Rowe was in the process of rejoining towards the safety fence, directly in the way of the race leader who had chosen the outside line with Farrell opting for the inside. Palmer’s car bounced off the turn four plating and was delayed sufficiently to see Farrell leading by around a half a dozen car lengths. With Moss unable to find any traction, the caution flags were deployed, and the race came to a halt. Farrell had the lead, but his advantage was minimal as Palmer sat directly behind him, and on the restart Palmer wasted little time in attempting to regain the lead with a hit on the rear bumper of the 667 car heading into turn one. Whilst Farrell tried to ride out the hit he could not avoid connecting the plating around the bend and onto the back straight incurring damage which ended his race, whilst at around the same time Kieren Bradford (27) became stranded at the end of the back straight which required another caution period. By this point, Ben Borthwick (418) who had started on the fourth row of the grid was now on the tail of Palmer with just two laps remaining. Palmer however judged the restart perfectly and whilst Borthwick attempted to connect with the leader’s back bumper on the final bend he was just too far back to do so, and Palmer crossed the line first. An array of former West Country F2 drivers from years gone by were on-hand to aid with the trophy presentations. Here's Garry Hooper (ex-686) Result: 24, 418, 251, 184, 302, 736, 460, 689, 315 and 35. Andy Smith helps out on the Farrell car post-race Heat three included Lewis Geach (111) who was racing his shale car given his keenness to make it out for what was possibly the final meeting at the track. It was a lively start as Ian Engalnd (398) ran headlong into the turn one wall with some force. That brought out the yellow flags, whilst Palmer was given a ride around the plating courtesy of Farrell, but without suffering any lasting damage. On the restart Driscoll led but most eyes were on the battle that was again brewing between Farrell and Palmer, and the hit from the new Grand National Champion shot Farrell fencewards. Farrell’s cause was not aided by the track surface on the wide outside line, which was extra slippery. He clouted the plating with sufficient force to cause significant damage that ended the young charger’s afternoon. On the restart Bradford and Justin Fisher (315) continued their eventful afternoon coming together in a heap on the home straight. By this time Borthwick had managed to catch and pass Driscoll just before half distance, but he appeared to be caught out by the track surface and drifted out wide on turns one and two allowing Driscoll back into the lead. Borthwick shadowed the yellow top onto the final lap and whilst this time he connected with the race leader, Driscoll managed to hold on for the win in another excellent finish. Result: 251, 418, 184, 24, 689, 302, 390, 111, 526 and 572. The Final for the Old Motorcycle Club Trophy was preceded by a demonstration from vintage motorbike sidecars, for nostalgic reasons. The race itself saw 19 starters with Driscoll’s hopes ending early when he and fellow visitor Phil Mann (53) became hooked together, with track debutant Jessica Smith (390) also becoming involved. Rowe led but Borthwick was swiftly through and into second with just five laps gone and soon after he grabbed the lead. By half distance Joe Marquand had moved up to second and despite closing in on the leader as the lap boards came out he was unable to mount a challenge as Borthwick successfully defended the magnificent trophy. Result: 418, 689, 302, 184, 24, 35, 315, 736, 526 and 460. Aptly, given the track’s uncertain future, the sun was beginning to set as the last race gridded. The race started in a similar fashion to the Final with Smith in a tangle heading towards turn three, this time with Cocks and Hatch, with the race brought under an early caution. On the restart Moon led a train of cars flying spectacularly around the track, the shakeout of which saw Marquand up into the lead, with Palmer making the move up to second and Vaight into third. With six laps to go Palmer made his move and pushed Marquand towards the turn one fence, Marquand dropping to fourth behind Weare. Palmer ran clear for the win, but Marquand was not going to give up on a final podium spot easily and managed to wrestle his way back past Weare to finish third. Result: 24, 184, 689, 418, 35, 315, 736, 320 and 27. Taunton – Sunday 14th November 2021 The final F2 meeting in the south-west for 2021 was, as per tradition, for the splendid Ladies Trophy which means a champagne overcoat awaits the winner of the Final. This late in the season it is unsurprising that a number of drivers had already turned their attentions towards 2022. Nonetheless amongst the 34 cars present there was an encouraging showing of visiting drivers, which included Harley Burns (992), Ben Farebrother (115) from the West Midlands, former Ministox star Charlie Sime (584), Ben Spence (903), and a north-west based trio of Gary Kitching (745), Jamie Ward-Scott (881) and the most frequent visitor of the season, Aaron Vaight (184). He was without the race car though as the transporter had broken down en-route. He would have been defending the Ladies Trophy. He completed the journey by car to ensure the trophy could be presented on the day. Following the unfortunate pre-meeting incident on the 23rd Oct which saw a heavy crash for Charlie Lobb (988) when his throttle stuck open, the youngster made a welcome return today. The opening heat began in dramatic fashion when Archie Farrell (970) spun away the lead and a yellow-grade pile up left Matt Peters (33) a little worse for wear, requiring an early caution. Blue top Joe Marquand (689) quickly hit the front, but it took superstar Justin Fisher (315) until five laps from home to dispose of Craig Driscoll (251) from second, by which time Marquand had checked out. A top ten finish for Lauren Stack from the yellow grade Result: 389, 315, 251, 667, 903, 948, 232, 746, 928 and 970. A strong showing from Dayne Pritlove (540) had him leading heat two until beyond half-distance when passed by Julian Coombes (828). The quickest man on track was teenager Harley Burns (992) who overhauled Coombes with four laps to go, while Paul Rice (890) shoved Coombes wide for second a couple of laps later. Track champion Jon Palmer (24) slowed to retire from fourth in the closing stages and would have to take his place in the Consolation alongside the likes of Chris Mikkula (522) and Dale Moon (302), who had also suffered mechanical woes. Diff problems for the 24 car Result: 992, 890, 828, 736, 115, 605, 35, 540, 526 and 572. The Consolation saw Mikulla the victim of a fencing from Charlie Sime (584), whilst Palmer and Moon had made light work of the opposition to run 1-2 by half-distance. Palmer didn’t appear to have the ultimate pace and after being bumped wide by Moon with three laps to go, immediately slowed to retire once more with recurring differential problems, his afternoon done for. Moon won from Lobb, and debutant ex-Ministox racer Jordan Butcher (509). Peter and Steve Gilbert lend a hand on the 24 car after another diff failure Chris Mikulla was fenced hard by Charlie Sime Result: 302, 988, 509, 762, 584, 663, 33 and 636. After the Ladies Trophy was paraded through the grid by sisters Millie and Stella Farrell, brother Archie again contributed to a chaotic start in the Final when he spun and was collected by Pritlove, with Butcher then spinning away the lead on the back straight. With a number of the yellows and blues also tangling, and John Brereton (948) left stranded facing the traffic on turn four, an early caution was called which gave Butcher a reprieve as he returned to the head of the field from Sime, Coombes and a dangerous looking Rice already fourth. Coombes took over the lead before a back straight spin put Rice ahead from Sime, Charlie Fisher (35) and Tommy Farrell (667). Fisher and Farrell moved into second and third around half-distance but, as the leaders negotiated backmarking traffic, neither the chasing duo nor Burns – recovering from getting delayed in the early going – could catch Rice who took the flag to add his name to the illustrious roll of honour on the Ladies Trophy. The action wasn’t over, as Archie Farrell clipped an inside marker tyre after crossing the line, launching himself into a roll to complete an entertaining showing from the youngster in the meeting in memory of his grandmother. Archie alongside his handiwork At the trophy presentation, a delighted Fisher spoke for many when he said, “For us, this is like the south-west World Final.” While an equally pleased Rice added, “I don’t think I’m too keen on what’s about to come!” in reference to the traditional ‘champagne overcoat’ he was about to receive. Result: 890, 35, 667, 992, 302, 584, 988, 526, 903 and 828. Burns produced a dominant performance to win the Allcomers race for the Trackscene Trophy, leading from before half-distance. Tommy Farrell pushed past Coombes for second with five laps to go, but didn’t leave his prey enough space on the back straight, and the pair tangled with spectacular results. The 828 car went up the wall and rolled onto its roof, leading to a stoppage. Pritlove passed Farrell as the incident unfolded, but he was shuffled back down the order in the restarted race, with Farrell and Moon completing the top three. Mikulla was fourth, despite a heavy hit into the home straight wall after another clash with Sime earlier in the race, while Rice came through to sixth from the lap handicap after a last bend sort out. Result: 992, 667, 302, 522, 35, 890, 988, 315, 605 and 540. That completes the south-west scene for 2021. Continues below:

-

The best yet - perfection

-

Pics from Skegness now in the gallery. A good day for Jack Witts with a brace of wins, and some hard hitting action from the Saloons.

-

Last night's King's Lynn pics now in the gallery

-

Continued from above: I used to catch a Barton bus from Nottingham to Long Eaton back in the 70s so have always liked their livery. Here we have 966 RVO, a 1963 dual-door Yeates bodied Bedford VAL14. (Pic credit David Mitchell) London Country liveried Routemasters RML2412 (JJD 412D), and RML2234 (CUV 334C) sandwich Green Line liveried RMC1469 (469 CLT). The last acted as a styling prototype for the longer RCL-type Green Line Routemasters but lost its amended body to RMC1502 at a subsequent overhaul. However, it has been restored with RCL style wide front blind-box, side transfers, and deeper wings. (Pic credit David Jukes) Impressive Exhausts: Shortly after leaving King’s Cross, Doncaster’s V2 2-6-2 No 60889 darkens the sky at Holloway on 3 April 1955, when heading the 9.59am relief to Edinburgh. The locomotive was burning brickettes, which contributed to the pyrotechnics. No doubt the local residents would be none too happy, especially if the washing was out! (Pic credit Philip Kelley) BR Class 6MT 4-6-2 No 72008 Clan Macleod puts out an impressive display when departing from Perth with the 4.45pm fish train from Aberdeen to Manchester in 1965 (Pic credit WJV Anderson) Grubby ’Princess Coronation’ No 46256 Sir William Stanier F.R.S. comes charging up Shap with a Glasgow to Birmingham express on 14 September 1955 (Pic credit WJV Anderson) Diesels could also ‘put on a show’ and, here, the roar of the twin engines from ‘Deltic’ Royal Highland Fusilier are producing a strong exhaust at Belle Isle, as D9019 lifts its train up the bank out of King’s Cross on 20 October 1968 (Pic credit Brian Stephenson) A big round of applause if you've stayed with me this week! Next week is the final one for this Off Season. Racing-wise we’ll have a look at the last Birmingham meeting, plus three F2 meetings from the south-west, before we make tracks to see what gems remain of a once busy summer Saturday railway line.

-